And the Waltz Goes On

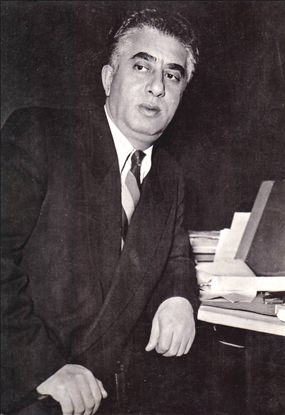

Aram Khachaturian.

You might be surprised to

know that the title And the Waltz Goes On is actually an orchestral piece

composed by the actor Sir Anthony Hopkins, better known perhaps for his

portrayal of the psychiatrist and cannibalistic killer, Dr. Hannibal Lecter in

The Silence of the Lambs. He wrote the waltz over fifty years ago,

before he made a name for himself in acting and he’s written several pieces

since, including a work called The Masque of Time which was given its

first performance a few years ago by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra.

Oddly enough, there is a

British composer with a similar name, the broadcaster Antony Hopkins best known

for his BBC radio series, Talking about Music, which ran for nearly forty

years.

I suppose for Australians,

mention of the waltz brings to mind Waltzing Matilda, the words of which

were written by one Andrew Barton Paterson. He was more commonly known by the

unlikely name of Banjo but not because he played one; it was evidently the name

of his favourite horse. Banjo Paterson went on to write many poems about life

in the outback but Waltzing Matilda is the best-known. Some years ago,

it was discovered that 28 percent of Australians would like the song to be their

national anthem.

As you might expect, the

word “waltz” has German origins and almost certainly comes from the verb

walzen, meaning “to turn or roll”. A similar dance in triple metre was

popular as early as the 1580s but around the middle of the eighteenth century

the rural people of southern Germany began dancing the Walzer, a dance

for couples which caught on quickly in urban areas too.

While the older minuet

remained popular with the aristocratic classes, it must have seemed terribly

old-fashioned and stuffy to the younger crowd. Although the spectacle of two

people dancing so intimately shocked many of the older generation, the waltz

became something of a craze. It was especially fashionable in Vienna and around

this time, one observer wrote that the Viennese were “dancing mad”.

Johann Strauss II

dominated the dance music scene in Vienna during the nineteenth century and his

orchestra provided the music for many grand balls. If these things interest

you, the word “ball” comes from the Latin word ballare, meaning “to

dance”. Strauss composed over four hundred waltzes, polkas, quadrilles and

other types of dance music, as well as several operettas and a ballet. The

waltz was so popular that it appeared in symphonies by Tchaikovsky, Dvořák and

Mahler in much the same way that the minuet was used in symphonies a hundred

years earlier.

Unlike the waltzes of

Johann Strauss, those of Frédéric Chopin are notably different in that they were

not written for dancing but for concert performance. Chopin started writing

waltzes for piano in 1824 when he was fourteen, and during his life wrote about

eighteen of them although others have probably been lost.

Aram

Khachaturian (1903-1978): Waltz from Masquerade Suite.

Moscow Chamber Orchestra cond. Constantine Orbelian. (Duration: 04:15; Video

480p)

Aram Khachaturian is the

most important Armenian composer of the twentieth century. He wrote this music

in 1941 and it was originally intended to accompany the play Masquerade

by the nineteenth century painter and poet Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov.

The music is best known

today as a five-movement suite but the famous waltz theme didn’t come easily to

Khachaturian. He evidently had something of a struggle composing it, but having

got over that particular hurdle it seems that the rest of the waltz came to him

easily.

This well-known Russian

orchestra gives an energetic performance of this meaty piece and if you are the

dancing type, you’ll probably be on your feet in minutes.

Maurice

Ravel (1875-1937): La Valse.

Orchestre Philharmonique

de Radio France cond. Myung-Whun Chung. (Duration: 12.55; Video 360p)

Ravel was a composer who

invariably did things differently and this waltz is a fine example of his

sophisticated use of musical ideas and brilliant orchestration. He called it a

“choreographic poem for orchestra” and began it in 1919. It was conceived as a

ballet but these days it’s usually performed as a concert piece.

This French orchestra

gives a beautifully shaped and controlled performance, conducted by the

distinguished South Korean pianist and conductor Myung-Whun Chung.

Although there are

unmistakable echoes of the nineteenth century, this powerful work couldn’t be

more removed from the innocent melodies of Johann Strauss that charmed the

Viennese. It seems more like a nightmare from a haunted ballroom. It beings

quietly with ominous rumbling of double basses and cellos but gradually the

tempo and intensity increase, fragments of tune appear then swirling melodies

are emerge. You can even get an unsettling sense of foreboding organic growth

within the music, as it hurls itself towards an almost terrifying but inevitable

conclusion.