Rivers of Life

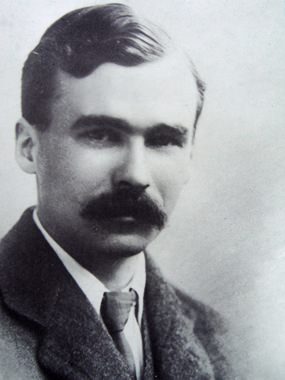

George Butterworth

in 1914.

“A river,” wrote Laura

Gilpin, “seems a magic thing … a magic, moving, living part of the very earth

itself.” Now Laura Gilpin you might recall, was an indefatigable American

pioneer photographer remembered not only for her expressive portraits of Native

Americans, but also for her monochrome photographs of south-western landscapes.

As a child, her mother encouraged her to study music, and she even spent five

years at the New England Conservatory of Music. As it turned out, her musical

talent did not blossom as anticipated but instead she became one of the great

names in photography who in addition, became one of the finest exponents of

platinum printing.

In his short piece

River of Life, the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell wrote, “The more we live,

more brief appear our life’s succeeding stages.” Anyone over a Certain Age will

recognise a melancholic ring of truth in that. “Life is like the river,” Emma

Smith wrote; “Sometimes it sweeps you gently along and sometimes the rapids come

out of nowhere.” I suppose most of us have experienced that sort of thing.

Comparisons between rivers and life it would seem are hard to resist.

Battles have been fought

over rivers or at least, close to them. The Battle of the Somme was a horrific

and tragic episode during the First World War, involving British and French

troops against those of the German Empire. The battle began in July 1916 and

raged for over four months on both sides of the River Somme in France. By the

following November, over a million soldiers had been killed or wounded.

One of them was

31-year-old George Butterworth, a Lieutenant in the Durham Light Infantry who

had already been awarded the Military Cross for bravery. On 5th August

1916 in the muddy trenches near the river, he was killed by sniper fire. Few

other soldiers, including his commanding officer were aware that Butterworth was

one of the most promising young English composers of his generation.

George Butterworth (1885-1916): The Banks of Green Willow.

National Children’s Orchestra of Great Britain, cond. Roger

Clarkson (Duration: 06:34; Video: 480p)

Although he was born in

London’s Paddington district, the family soon moved to Yorkshire so that his

father could take up an appointment as General Manager of the North Eastern

Railway. The boy received his first music lessons from his mother and he began

composing at an early age, playing the organ for services in the chapel of his

elementary school. He won a scholarship to Eton College and later in life

became a close friend of composer Ralph Vaughan Williams.

The Banks of Green Willow

was written in 1913 and it’s a pastoral piece, based loosely on a folk song that

Butterworth heard and wrote down in Sussex. The title implies a musical picture

of a river somewhere in England, but we don’t know exactly where. The work is

given a lively performance by the National Children’s Orchestra of Great

Britain, a well-established organisation in the UK. Hearing these young

musicians playing with such commitment and maturity it is hard to believe that

they are all less than thirteen years old.

Like so much of the music

by Delius and Vaughan Williams, this work sounds utterly English. It’s a

picture of the England that Butterworth loved so much and for which, like so

many others, he fought for - and paid for - with his life.

Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884): Die Moldau.

Chamber Orchestra of Europe, cond. Nikolaus Harnoncourt

(Duration: 14:38; Video: 360p)

Unlike Butterworth’s

meandering English river, we know exactly where this one lies. Bedřich Smetana

is known today as the grandfather of Czech music because he pioneered a totally

national musical style.

Má Vlast,

meaning “My Homeland” is a set of six symphonic poems that Smetana wrote during

the 1870s and one of the movements is called Vltava, also known by its

German name Die Moldau. It describes the journey of the Vltava River

from its source in the Bohemian mountains through the countryside to the city of

Prague. The Czech name probably comes from an old Germanic expression wilt

ahwa, meaning “wild water”. The piece contains Smetana’s most famous

melody, an adaptation of a borrowed Moldavian folksong which is strikingly

similar to the tune of the Israeli national anthem.

Despite the slowish tempo,

this is one the most expressive recent recordings I’ve heard. It’s beautifully

timed and phrased with responsive playing from the orchestra. It starts with a

musical impression of two springs, with water bubbling out of the earth, which

eventually leads into the main theme. There are musical snapshots of a hunt in

the forest, a peasant wedding, water-nymphs in the moonlight, St John’s Rapids

and finally the concluding section in which the river triumphantly enters Prague

and then flows majestically away into the distance.