Nowhere does the solitary splendour of the Himalayas

whisper to the traveller its most powerful message, than when it speaks

through the majesty of its Annapurna Range. One need not climb a mountain to

be dazzled by it.

One

of the deepest valleys in the world, the Kali Gandaki forms the western

boundary of the sanctuary

One

of the deepest valleys in the world, the Kali Gandaki forms the western

boundary of the sanctuary

Rising abruptly from verdant forests of rhododendron,

bougainvillaea and bamboo, the Annapurna forms a magnificent arc of

snow-mantled peaks, five of which bear the name Annapurna. By tradition, the

Nepalese believe these mountains are the home of deities. For centuries both

Buddhist and Hindu devotees have made the pilgrimage to the sacred shrines at

Muktinath.

Today, pilgrims of a different kind are flocking to this

area for trekking adventures. A three to four week hike along the circuit

trail around the range, or an 8,500 foot climb up the Modi Khola Valley into

the Annapurna Sanctuary is a journey made in the shadow of the gods.

Local

villagers are dedicated to protecting the fragile beauty of the park

Local

villagers are dedicated to protecting the fragile beauty of the park

Much more than a park, the thousand square mile Annapurna

Conversation Area Project was established in 1986, and incorporates

environmental management and the cooperation of the local inhabitants. The

creation of the park came none too soon, for the fragile beauty of the region

needed protection.

Sculptured fields of millet and corn cover the high slopes

above the Kali Gandaki Valley, which forms the western boundary of the park.

One of the deepest valleys on Earth, the Kali Gandaki lies between Dhaulagiri,

the world’s seventh highest mountain.

Outdoor

latrines help curb trail waste but foul the local water

Outdoor

latrines help curb trail waste but foul the local water

With its grandstand view of the snow-capped Annapurna Range

to the north, and the subtropical Pokhara Valley to the south, the meadow

known as the Austrian Camp is a favorite stop for groups who are hiking the

200 mile trail through the conservation area.

Long closed to outsiders, the idea of introducing a

national park in this region was opposed by the native population for fear of

threat to their environment and Himalayan culture. There was a great deal at

stake. They had heard of whole villages being moved to make other Nepalese

parks wild enough to accommodate the trekkers’ expectations, and of families

that died of tropical diseases after forced relocation. The King Mahendra

Trust and the World Wildlife Fund set down a plan which makes the park and the

villagers self-supporting. Today villagers have learned to live with the

tourists and the trekkers, and relations between the locals and the visitors

are amicable. The park is now the most popular trekking area in Nepal.

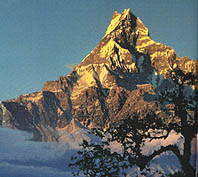

The

sacred summit of the Machapuchare is a Nepalese deity and off limits to

climbers

The

sacred summit of the Machapuchare is a Nepalese deity and off limits to

climbers

Here the awesome Himalayas pause and step back to expose an

amphitheatre three miles wide. Rising directly from its walls are nine peaks

over 21,000 feet high, each draped in a shattered cascade of glacial ice. Far

below the eternal snows, meadows and streams roll across the undulating floor

of the sanctuary. The trail is clean. The visitor is surrounded by beauty, not

trash. The master plan works because the local people make it work. And the

wildness of the surrounding landscape is in good hands.