by Chalerm Raksanti

The Rabari are one of perhaps a dozen or so castes of

livestock-breeding, semi-nomadic peoples of northwest India. Their origins

are unknown, and old census reports dismiss them as camel rustlers, cactus

eaters, and stealers of wheat. They have also acted as messengers to great

armies during regional warfare.

Rabari

bride being tattooed before her wedding.

Rabari

bride being tattooed before her wedding.

According to one tradition, all the Rabari once lived

in Jaisalmer, in the state of Rajasthan, in the Great Indian Desert. Over

the centuries they spread into many other states, integrating themselves

into Hindu culture as they went, splintering into countless sub-castes,

but always retaining their unique ways and differences.

Today, it is clear that in modern India their way of

life is in trouble. The Rabari population is estimated to be about

270,000. They now often keep only a few camels for transport. Many earn a

living by selling sheep and goats for meat, dung for fertilizer, and wool.

With open land filling up through development, and conflicts with settled

people increasing, more and more the Rabari are forced to give up their

herds and look for other work.

Herdsman

assists a kid to suckle.

Herdsman

assists a kid to suckle.

An early October morning in Gujarat finds the Rabari

camped in tarpaulin shelters, preparing for their annual migration they

call the “dang”. This is when groups of from five to fifteen families

set out with their livestock in search of green pasture. They wander from

autumn through the following spring, during the dry months between the

southwest monsoons. There is an urgency to get all the work done in

preparation to decamp. Women run barefoot over stones and thorns, chasing

lambs. The shepherds pound the ground with their staffs and curse the

sheep as they corral them into makeshift pens. Each shepherd has a

slightly different call, whistle or shriek to call his flock and the noise

is deafening. Then one watches the gentle firmness with which a herdsman

will get a reluctant goat to suckle a kid and realizes how precious these

animals are to the Rabari.

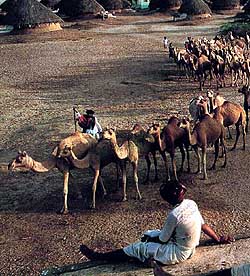

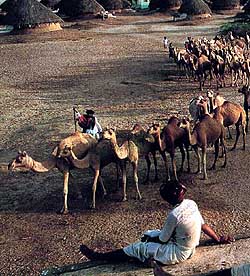

Rabari

camel train departs for greener pastures.

Rabari

camel train departs for greener pastures.

By day the Rabari men guard their animals from wolves

and jackals. The forests are also crawling with bandits. At night he herds

them together with other men’s livestock for protection against thieves.

A pistol or a rifle is essential for protection, but most Rabari have only

their staffs and sling shots. Besides stealing animals, the bandits often

kidnap women for random. Village police provide no justice since the

system is rife with corruption.

Fine

hand crafted jewelry adorns this woman’s hands during festive occasions

Fine

hand crafted jewelry adorns this woman’s hands during festive occasions

Throughout India grazing land is rapidly shrinking.

Previously, farmers and nomads enjoyed a symbiotic relationship. Pastoral

nomads provided farmers with dung in exchange for grazing privileges.

There was enough room for everyone. The farmers tilled the arable land and

the grazers fed their herds in land unfit for farming. Unfortunately,

times have changed and although the farmers still want the dung, they do

not want the nomad’s herds eating the cash crop standing between them

and financial ruin.

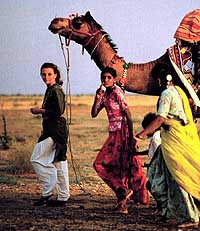

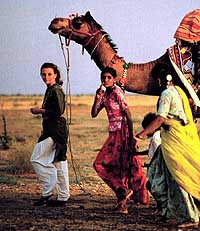

Young

Rabari women on the trek across the Great Indian Desert.

Young

Rabari women on the trek across the Great Indian Desert.

Still one can still see a timeless train of camels

leaving the villages and setting off for the Rabari’s annual migration.

They migrate south in a rough loop, through a labyrinth of sea and desert,

into the fertile farmlands of the neighboring Surashtra region, then back

again before the advent of the pounding monsoon rains.

Rabari

bride being tattooed before her wedding.

Rabari

bride being tattooed before her wedding. Herdsman

assists a kid to suckle.

Herdsman

assists a kid to suckle. Rabari

camel train departs for greener pastures.

Rabari

camel train departs for greener pastures. Fine

hand crafted jewelry adorns this woman’s hands during festive occasions

Fine

hand crafted jewelry adorns this woman’s hands during festive occasions Young

Rabari women on the trek across the Great Indian Desert.

Young

Rabari women on the trek across the Great Indian Desert.