by Chalerm Raksanti

Today, despite the Spartan living conditions of most of

China, and a government whose control reaches into the most intimate

aspects of people’s lives, many Chinese, even those in Beijing, closest

to the center of control, manage to enjoy happy lives with their families,

to pursue their private passions, and to find please in unlikely places.

A

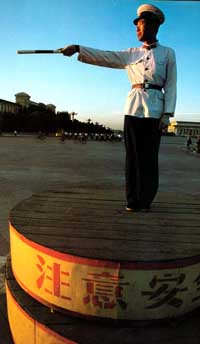

baton-wielding traffic policeman stands on a platform in Tiananmen Square.

The sign warns, “Pay attention to safety.”

A

baton-wielding traffic policeman stands on a platform in Tiananmen Square.

The sign warns, “Pay attention to safety.”

Far from being the soulless blue ants of yesteryear,

the people of the city are avid movie-goers, tireless tourists and sports

enthusiasts. At dawn, the parks of Beijing are filled not only with old

folks, moving through the ancient rhythms of taijiquan, but also with

legions of young joggers and aerobic exercise freaks. Settling into the

city’s rhythms one must learn where to look. Stamp collectors meet on

park benches and sell or exchange their postage stamps from around the

world. Some people congregate with pets, pedigreed Western dogs, caged

songbirds, and amateur horticulturists abound.

This

pheasant-plumed actress impersonates a warrior in a Beijing Opera

production.

This

pheasant-plumed actress impersonates a warrior in a Beijing Opera

production.

But the center of life for the Chinese is unremitting

labor. They have overcome Beijing’s natural handicaps and the ravages of

successive invasions, and established the city as a world capital.

Ambitious irrigation schemes, some begun more than 2,000 years ago,

transformed the arid North China Plain into a productive agricultural

region. The Grand Canal was extended in the 7th century to link the

Beijing region to the towns of the Yellow and Yangtze River Valleys.

Seat

of power during the Quing Dynasty, the imperial throne stands in the Hall

of Mental Cultivation in the Forbidden City.

Seat

of power during the Quing Dynasty, the imperial throne stands in the Hall

of Mental Cultivation in the Forbidden City.

Since 1949 the Chinese have also added thousands of

miles to their rail network to tie the rest of China more closely to the

capital. Beijing’s people are tough and resilient. Their ancestors

labored to build and rebuild the city and over centuries impressed their

own character on it, triumphing over a harsh climate and foreign

invasions, and surviving indifferent and brutal leaders. Today’s

citizens are worthy successors, and their city’s survival and growth

make it a fitting symbol for all of China.

In

Beijing, as many as 500 bicycles may cross an intersection every minute.

In

Beijing, as many as 500 bicycles may cross an intersection every minute.

Finding your way around Beijing is relatively simple.

Surviving to tell the tale is something else. A Beijing traffic jam is a

lurching, heart-stopping amalgam of motorcycles, three-wheeled vans,

articulated buses with accordion-pleated center sections, and in all of

this mess seems all the city’s 4 million bicycles molded into a thriving

hive of flexing leg muscles and elbows. The basic rule of the road is that

the streets belong to the cyclists who ply the roads as though other

vehicles do not exist. Heedless of stoplights and pedestrians, the traffic

virtually hums like a wasp’s nest. The beleaguered traffic policemen try

to restore order, but nothing works for very long. When Chinese are in a

hurry, red lights, traffic cops and lane markings mean nothing at all.