Do you remember that song? It was one of Cole Porter’s most popular hits and written in 1932 for the musical Gay Divorce. Those were the days when for most people, the word “gay” had rather a different connotation than it does today and meant cheerful, carefree or light-hearted. Over the years, the song Night and Day was recorded by dozens of people and it’s fascinating from a technical viewpoint. It has an unusual structure for its time and uses surprising and rather complex harmonies. Cole Porter studied classical music at Yale University and became one of the major songwriters for the theatre. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Porter wrote both the lyrics and the music for his songs. According to writer Melissa Block, Night and Day was heavily influenced by an Islamic call to prayer that the composer had heard while travelling in Morocco, thus bringing a pleasing touch of irony to the story.

Many pieces of classical music were inspired by a particular time of night or day, and last week, having nothing much to do recently I started to make a list of them. Yes, sad I know, but my excuse is that there was an all-day power cut in the village and little else could be achieved. One of the first pieces that came to mind was the overture to Morning, Noon, and Night in Vienna by the studious-looking Austrian composer Franz von Suppé. He wrote about thirty operettas, nearly all of which have faded into obscurity though some of the lively overtures are still performed. At birth, Suppé’s parents, perhaps in a moment of temporary insanity, christened him Francesco Ezechiele Ermenegildo Cavaliere di Suppé-Demelli. but he sensibly abbreviated this elephantine name at the earliest opportunity.

Most of the classical pieces I could recall were about evening or night rather than the daytime. There’s that lovely piece by Delius, Summer Night on the River and the sumptuously harmonic Verklärte Nacht by Schoenberg, written before he ventured down the musical cul-de-sac of serialism. Then there’s Khachaturian’s nocturne from the Masquerade Suite and of course all those other nocturnes by Chopin, Fauré and Liszt. The word “nocturne” (usually in its Italian form of Notturno) was first applied to 18th century ensemble pieces. The music was not intended to be evocative of the night, but was for an evening performance such as a courtly dinner party. By the 19th century to meaning has changed to describe a piece for solo piano, a form developed by the Irish composer John Field, who wrote nocturnes with a song-like melody over a guitar-like accompaniment.

Two other well-known nocturnal pieces are Manuel de Falla’s brilliant Nights in the Gardens of Spain and Mussorgsky’s hair-raising Night on the Bare Mountain, known by alternative English titles depending on how the original Russian is translated. You can probably think of other examples, but here are three piece that are linked with morning, afternoon and night.

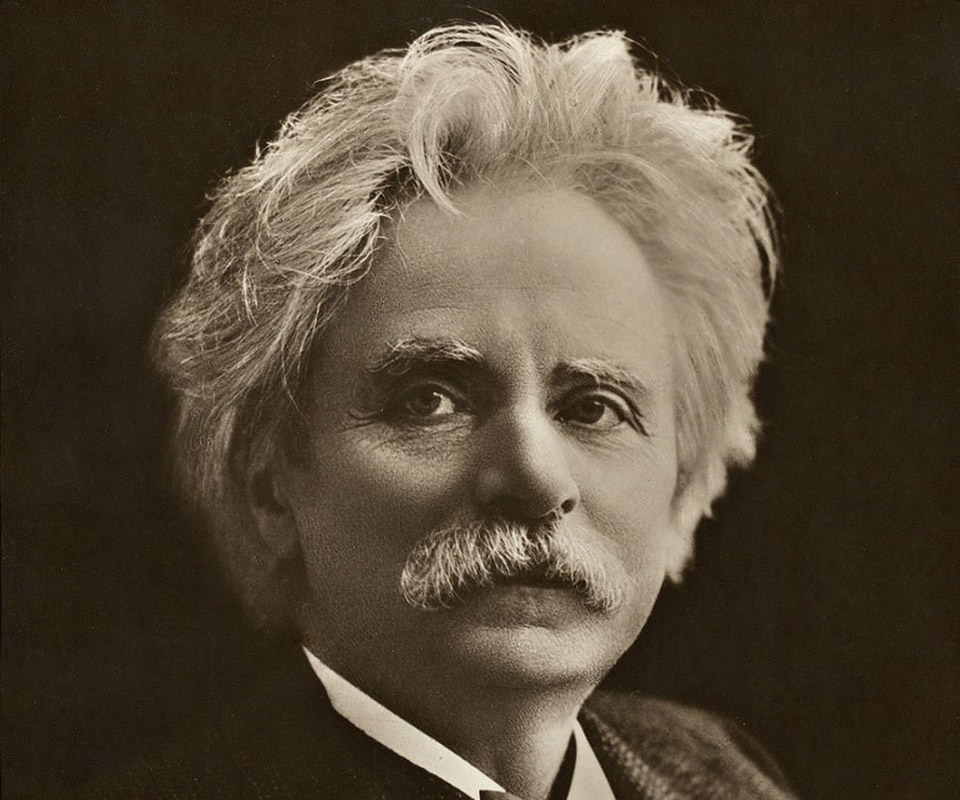

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907): Morning Mood from Peer Gynt Suite No 1. Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Zubin Mehta (Duration 04:08; Video 1080p HD)

This piece has acquired international fame through its use in films and television programmes. Edvard Grieg provided the incidental music to Henrik Ibsen’s 1867 play of the same name, which describes the adventures and dubious exploits during the life of Peer Gynt. About twenty years later, Grieg extracted various sections of the music to create two suites each of four movements, though why he waited so long is anyone’s guess. Morning Mood is the first movement of the first suite, and many people assume that it depicts Peer Gynt gazing heroically over some Nordic landscape.

In fact, it comes from the fourth act of the play, when the sun rises to reveal our eponymous hero clinging to the branches of a tree in Morocco to escape a horde of grunting apes below. This is a memorable performance, given in 2015 outside the magnificent Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the incomparable Zubin Mehta.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918): Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra cond. Andrés Orozco-Estrada. (Duration: 11:45, Video: 720p)

This evocative work (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun) was written in 1894 and was inspired by a poem of the same name by the Parisian poet and critic Stéphane Mallarmé. The music was years ahead of its time, consisting of a complex organization of musical cells and motifs. It’s not descriptive in the usual sense of the word, but more of a musical interpretation of the poem using rich whole-tone harmonies and daring orchestration. Stéphane Mallarmé was much impressed with Debussy’s music though to many people it must have sounded unbearably modern. Leonard Bernstein wrote with characteristic vision that the work “stretched the limits of tonality” and in so doing, set the harmonic stage for the atonal music of the century to come.

Debussy himself wrote: “The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads, he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature.” In 1912, Vaslav Nijinsky choreographed Debussy’s work for a ballet of the same name. And in case you had forgotten, a faun is a half-human and half-goat mythological creature that frequently appears in Greek and Roman mythology and evidently preferred to reside in quiet, rustic or desolate places.

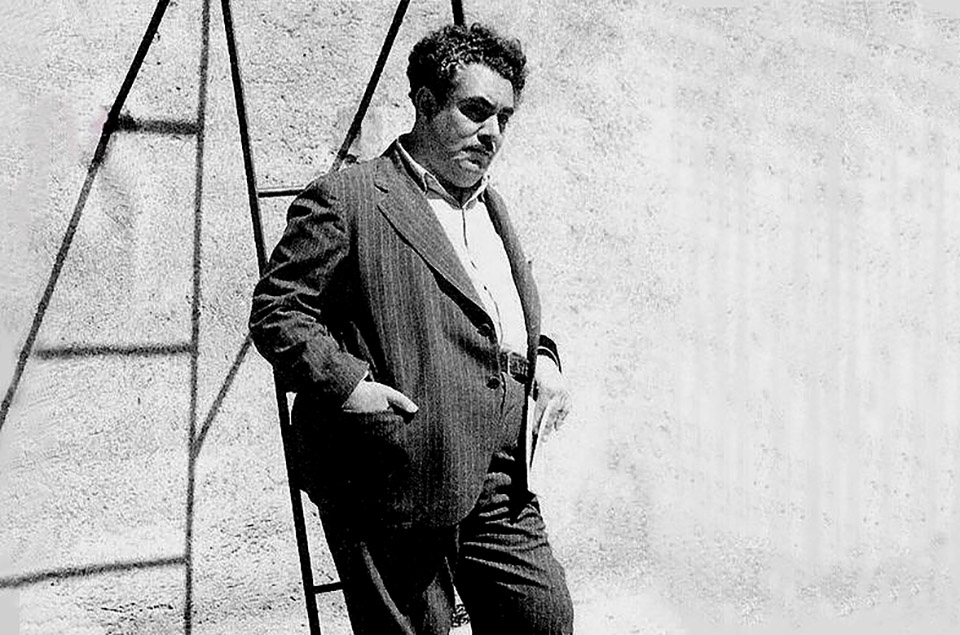

Silvestre Revueltas Sánchez (1899-1940) Noche de Encantamiento (Finale). Orchestre de Paris cond. Kristjan Järvi (Duration: 13:15; Video: 720p HD)

Revueltas is considered one of the most significant composers of twentieth-century Mexican music. He used dissonance freely and his works have a rhythmic vitality and raw energy. He once wrote, “My rhythms are booming, dynamic, tactile and visual”. Although Revueltas wrote chamber music, songs and several other works, his best-known composition is the score for the 1939 Mexican film La Noche de los Mayas (“The Night of the Mayas”) about the cultural clash between a tribe of Mayans and the modern world. Like Grieg, Revueltas decided to create an orchestral suite from the dramatic music but he died before even starting it. The work was taken up by his brilliantly talented younger compatriot and conductor, José Ives Limantour and the reworking of the original film score preserves the composer’s use of native Mexican rhythms.

Limantour conducted the first performance with the Guadalajara Symphony Orchestra in 1961. Like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, this symphonic suite is evocative, ritualistic music, and it ends with a wild sacrificial dance calling for eleven percussionists. It uses a selection of traditional Mexican instruments including the caracol, guiro, huehuetl, sonajas, tumbadora and the tumkul. The work is symphonic in design and cast in four movements with this one, Night of Enchantment being the last. You’ll need a good sound system to fully appreciate this thrilling and relentlessly percussive music. It’s real blood-and-guts stuff and not music for wimps or those of a delicate disposition.