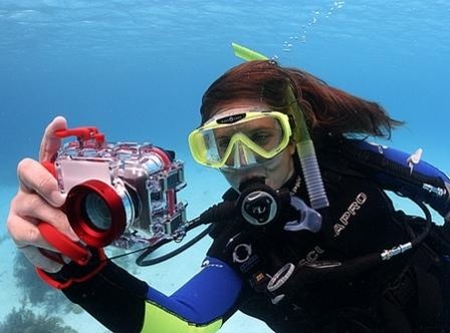

With the floods that we have had recently, there is probably more than one camera that went swimming, and is now (hopefully) the subject of an insurance claim. However, there is truly another world beneath the surface.

A few years back, one of our avid underwater explorers wrote and suggested I should write on this subject. What he did not know, being a weekend flipper and snorkel type as he was, is that I get nervous if the water reaches my knees. Many years ago I struck a bargain with sharks, those denizens of the deep with the amazing dentition. The deal was that I would not swim in their bath water, if they would refrain from swimming in mine. I have been true to my word, and they have also, with no dorsal fins seen anywhere near my bath tub. So because of my fear, my knowledge of underwater photography is restricted to shooting through the portholes of swimming pools!

I actually did a camera test many years ago on the ferociously expensive Nikonos cameras. It was easy to clean – you just directed the garden hose at it, and all the sand washed off (after I had bravely put it under the surface and photographed the model’s feet).

However, with the advent of cheap underwater cameras these days (even disposable ones), you do not have to invest in a Nikonos to try getting a few shots beneath the surface.

Now comes the technical stuff. Not only can you not breathe sea water, what has to be remembered is that water (especially sea water), is 700 times more dense and 2000 times less transparent than air. Even though it may look crystal clear down there with the dugongs, it is not. It has been suggested to me that if you are using natural light (that is from the sun above the waves) then do not go lower than seven meters below the surface. That is five meters deeper than I am high – that definitely precludes my trying it.

For these reasons, underwater photographers will use wide angle lenses, so that they have to be close to the subject, so there is then less water between the camera and the item being photographed. If it is a large fish with teeth, you need to be a knee tremblingly three meters from it, to get a good shot. Far too close for me! Those that claim to know (and I do know a couple of underwater photographers who so far have neither been eaten or drowned) say that a focal length lens of between 28 mm and 15 mm (almost a ‘fish eye’) would be appropriate for 35 mm cameras.

Another tip given to me by the wet-suit and water-wings brigade is to take the meter reading on the surface and open up the aperture one f stop for every three meters depth.

Again when using sunlight, the best time of day is the exact opposite from the above the surface shooter. Forget early morning and late afternoon, as the sun’s rays get reflected away from the surface of the water. The best time is when the sun is directly overhead and the light penetrates the water more easily.

You may have also noticed that underwater shots can have strange colors. This is because the light becomes diffused as it travels through the water, and the different colors, which have different wavelengths, become absorbed at different rates (or depths). Red is the first to go and yellow is the last. The predominant color is then usually bluish or greenish, which explains why underwater shots have that color cast. You can counteract this by manipulation in the computer with your electronic paint brush.

However, whatever the technicalities, if you just want to try something different one weekend, buy one of the inexpensive throw-away waterproof cameras, stay just under the surface and see what you get. You will probably be delighted with the results. But if you are considering SCUBA diving with a spear gun in one hand and a camera in the other, you will need much more specialized equipment! Glug, glug.