Sum rap Thai literally means “a Thai set,” and applies to the correct serving and pairing of Thai dishes.

Popular Thai food critic and writer Mom Luang Sirichalerm Svasti, who goes by the pen name Chef McDang, writes in his book Principles of Thai Cookery, “We think of all parts of the meal as a whole – sum rap Thai (the way Thais eat), is the term we use for the unique components that make up a characteristically Thai meal.”

In essence, sum rap Thai conveys firstly how a meal is served and eaten, including for class and regional variations; and secondly how particular dishes are paired with others.

Thais have become more sophisticated in their eating habits over the past two centuries, explains McDang, and “Sum rap Thai is a fairly new invention in Thai food culture. It came about as the country is the land of plenty and people have become richer, and the abundance of raw materials to cook with has expanded.”

“In ancient times we considered rice a meal.” McDang continues. “We ate it with fruits and fish sauce; or something as simple as just sticky rice and jaeow (a northeastern Thai or I-San style dip). This would still constitute a meal. So do not mistake the ancient way of eating with sum rap Thai,” reiterating that sum rap Thai was “invented by sophisticated Thai diners later on in Thai culinary history.”

How to order Thai food

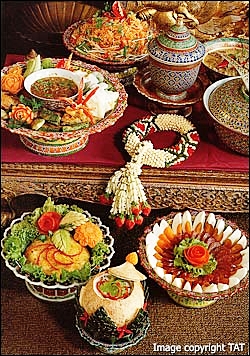

A typical Thai meal set today includes a curry; a stir fry vegetable usually with meat; a fried dish; soup; a tart salad-like yum; and a dipping sauce (kreung jim) with cooked and/or fresh vegetables. In this list, McDang calls such dipping sauce condiments “perhaps most important of all”. But surprisingly, it is the dish least known to foreigners, and relatively rare to find in an overseas restaurant menu. Likened to a chilli jam or condiment, examples like nam prik, lohn and jaeow highlight the simplest of set menus. For example, a farmer packs his plaid pha khao mah cloth ‘lunchbox’ with rice and nam prik for protein, plus some local fruits and vegetables – a uniquely Asian version of a ploughman’s lunch. But that is not sum rap Thai.

In a more formal setting, the composition of all dishes is important. Soup, for example, clears the palate and washes things down. The remaining dishes all add contrasting yet complementary flavours and textures, but each one is individually different.

Presumably the reason so many tourists complain Thai food is too spicy-hot or too sweet is because they don’t marry or pair dishes of contrasting flavours. Simply put, not all Thai dishes are uniformly chilli-hot, so match a spicy yum or hot kaeng pa jungle curry with blander fried foods that coat the mouth. Likewise, sweet-savoury offerings foil chilli as do cooling soups and neutralising rice.

How Thais Eat

“Kin khao”, the colloquial invitation to dine in Thai, means ‘‘eat rice’’. Every Thai meal’s main glory is that grain, whether white, coloured, blended, sticky or standard. One can go so far as to state that all other dishes, known collectively as kap khao (which literally means with rice), are mere accompaniments.

“In Thailand everything is served all at once, and you eat it with rice,” explains McDang. “There are no courses.” Likewise, there is no appetizer, although there are snacks aplenty, especially for those grazing market stalls.

Hawker food aside, don’t order a single dish to consume on your own. Thai dining is the essence of relaxed conviviality, and the sharing of several dishes is part and parcel of the ritual. Rather, Thai diners communally portion dishes from the middle of the table. You are quite likely to see Thais doing the same thing when eating at fine French restaurants in Bangkok – it is ingrained in their culture.

A typical place setting features rice on individual plates for eating main dishes. Sometimes the rice is served separately in small bowls or from large communal bowls, then portioned on to a plate. While each person is served his own grain, other foods are served from bowls or small platters placed in the centre, then on to personal plates. Food is not scooped atop a rice bowl as in China.

More importantly, as individual dishes are consumed together as a set, uninitiated foreigners are cautioned not to dive into each dish when it first comes to table. Thais are seemingly lethargic until all the dishes are put before them — a full set or sum rap, so to speak. Even then, take only a small portion of one dish to consume at a time, before a second morsel from another platter. And unlike, say, an Indian meal where rice reigns at the plate centre with ‘courtier’ side servings ringed around, in a Thai meal one never takes everything at the same time.

One reason for this is Thai concepts of food temperature – or lack thereof. “Thais have no concept of hot food served hot, and cold food served cold, ’’ explains McDang. “It’s all room temperature. We live in the tropics, and we serve hot rice and ‘cold’ main dishes.”

Harried cooks will value the fact that preparing a Thai meal does not mean precise timing from stove to table. Although soups are invariably hot (“When hot food is eaten, it opens the pores in your mouth, giving you fresher tastes,” says McDang) and stir-fries easily cooked to order, other dishes like kaeng (or gaeng) curries are commonly served at room temperature. Granted, tropical room temperature may prove much warmer than in other parts of the world. Once a curry cooks, for example, it can sit well away from the stove until ready to eat or sell, and in fact, the flavour of many of these dishes improves during this slow steeping.

Spoon and Fork

In regional areas like Lao Isan and in the Lanna North, both where sticky rice prevails, locals still eat with their hands. But nearly two centuries ago Thais were introduced to forks and spoons. With most of the food cut or chopped into small mouth-sized pieces, knives remain an anomaly and are not provided outside of international restaurants. Likewise, chopsticks are reserved solely for streetside noodle dishes or dining in Chinese eateries. Consequently, Thai servings are pre-cut into portions small enough for a spoon, or tender enough to break apart using just a fork and spoon. In Thailand, never put your fork in your mouth – that is what spoons are for.

“The fork and spoon are well-suited to Thai food: the fork shepherds the food onto the spoon, which is then used to lift the food to the mouth,” McDang explains. By contrast, when eating rice and curries with a fork (as in the West) “you miss out on all the great juices and curry that are an integral part of the taste experience ”.

In an article he wrote for CNNGo, McDang goes on to discuss this concept of kluk (pronounced ‘klook’). “Use a spoon to get a real snapshot of what Thai food is about. Mixing different dishes into your rice with your fork and spoon, getting your own personal measures of each dish on your spoon each time. This is very important to Thai food: it’s part of our culture and makes eating so interesting because you get so many flavours and textures.”

When eating a Thai dish, counsels McDang, “Just shut your eyes, stick it in your mouth and just experience the flavours and textures blending in your mouth. You mix everything in your mouth and when you chew it you blend it all together.’’ We hasten to add, he is talking about eating one specific dish at a time, albeit with rice; not a combination of several dishes scooped together.

“This absolutely contrasts to French cuisine, where it is all blended before you put it in your mouth,” he explains, using the example of steak au poivre – with its pre-seasoning and sauce. “When you eat Thai cuisine, you can’t approach it like a Western meal.”

McDang notes that there are is also a sum rap-style set for Thai desserts, but warns that Westerners over the past century have not been especially enamoured of them. Thai desserts are essentially dumplings made from coconut milk or cream, palm sugar, salt, fruits, rice flour and sticky rice flour. They are generally very sweet. With Thailand offering some of the best tropical fruits in the world, many restaurants and households, especially those hosting foreigners, offer fresh fruits at the end of a meal as a refreshing palate cleanser.

Regional Flavours:

Regional examples of sum rap include northern khan toke, and northeastern I-san Palaeng – or dinner set, served from short-raised tables with guests sitting phub phiab cross-legged on the floor. Both are served with sticky rice, and in the case of Chiang Mai in the north, local specialties like nam prik num or nong chilli dip, crispy fried pork skins, Indian-spicy kaeng hunglay or herbal kaeng kae, and haw mok custard. “But for the Central Plains, a set meal means a lot more, because it means ‘what goes with what,’” says McDang. Central Thailand, which includes the capital Bangkok, is a trade entrepot. Consequently, it reflects the riches of a kingdom, not just one region. “So it’s why we started eating different dishes, with fusion included, from all the trade.”

In essence, the origin of sum rap Thai.

Do’s and Don’ts

Select a range of cooking styles and flavours: a soup, a curry, a salad, fried and deep fried dishes, for example.

Order several dishes to share; not per person.

Place dishes in the centre of the table, and serve communally.

Eat with rice.

Dish yourself a minimal portion of one item at a time; not all together.

Eat with your spoon, pushing food on to the spoon with the fork.

Be adventurous!

Perfect Pairing

“To a Thai, certain pairings are known innately,” states Chef McDang, noting that the variety of “accompaniments necessary for each dish depends on how rich or poor you are and whether you are able to procure these ingredients to accompany the dish.” Here are his recommended couplings of dishes “that have to be accompanied by other things to improve taste”.

Sour Curry (Kaeng Som)

Accompanied by:

Thai Omellette (Kai Jeow) or Fried Crispy Salty Fish (Pla Krop)

Kaeng Pa Jungle Curry “any style with any type of protein”

No coconut milk in these curries

Accompanied by:

Fried Salted Fish (Pla Khem Tot) or Salted Pork (Moo Dat Deow Tot)

Green Curry “with any kind of protein” (Kaeng Kheow Wan)

Accompanied by:

Crispy Fried Sun Dried Fish (Pla Salit Tot)

or Salted Fish (Pla Khem Tot)

or Salted Egg (Khai Khem)

Yellow Curry “with any kind of protein” (Kaeng Karie)

Accompanied by:

Toasted Coconut Chips (Maphrao Kua) or Fried Ripe Bananas (Kluay Tot)

Chili Dip in a Boat (Nam Prik Long Ruea)

Accompanied by cooked and raw vegetables such as cucumber or Curcuma (Khamin Khao)

or Crispy Flaky Fried Catfish Meat (Pla Duk Foo)

or Sweet Tender Pork Belly Pieces (Moo Wan)

or Salted Egg (Khai Khem)

Green Beef Curry with Fresh Garden Thai Chilli Peppers (Kaeng Kheow Wan Nuea Prik Kee Nu Suan)

Accompanied by:

Fried Roti (Roti Tot)

Chef McDang’s Suggested menu

Sum Rap # 1

Beef Jungle Curry with Pumpkin (Kaeng Pa Nuea Kup Fak Thong)

Stir Fried Chinese Broccoli and Salted Fish (Pat Kahna Pla Khem)

Coriander Roots, Thai Garlic and White Peppercorn Marinated Deep Fried Fish

(Pla Tot Kratiem Prik Thai)

Pork Broth with Vegetable, Ground Pork and Egg Custard (Kaeng Jued Look Lawk)

Fermented Soybean and Coconut Cream Dip with accompanying vegetables

(Lohn Tao Jeow)

Wing Bean Salad (Yum Tua Plu)

Sum Rap # 2

Green Curry with Pla Grai Fish Balls (Gaeng Kheow Wan Look Chin Pla Krai)

Hearts of Coconut Stir-fried with Chili Garlic and Prawns (Yot Maprao Pat Koong)

Spicy Vegetable Soup (Kaeng Liang)

Marinated River Prawns fried with Garlic, White Peppercorns and Cilantro Roots

(Koong Mae Nam Tot Gratiem Prik Thai)

Thai Beef Salad, Plah Style (Plah Nuea)

Fresh Young Tamarind Chili Dip with accompanying vegetable, sweet pork, and salted egg (Nam Prik Makham Sot Gup Pak Ruam, Moo Wan, Lae Khai Khem)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robert Carmack is author of several cookbooks, and writes widely on Asian food and travel. He and his partner Morrison Polkinghorne host gastronomic tours to Asia. To learn more, visit their websites www.globetrottingourmet.com and www.asianfoodtours.com.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to think Mom Luang Sirichalerm Svasti (“Chef McDang”) and Vatcharin Bhumichitr for their invaluable assistance in preparing this article.

Chef McDang has become a household name in Thailand, appearing both on television and in print. He is arguably the kingdom’s most famous food expert, and a respected ambassador for Thai cuisine.

Vatcharin Bhumichitr is a long-time restaurateur, and author of about ten English-language books on Thai and Southeast Asian cooking. His latest projects are building Cinnamon resort on Koh Samui and La Bhusalah near Chiang Mai. The latter is a resort incorporating a small cooking school and facilities for art courses. Nearby he has just opened a noodle restaurant.