There could still be a way of putting your children through university which does not involve accumulating huge debts or creating gaping holes in your bank balance.

Despite governments of the world’s biggest economies concentrating on the size of their own public debt, the massive amount of private debt is actually the real issue.1

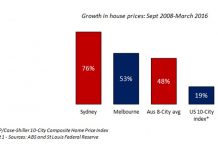

Slight progress has been made on that front – for example, household debt as a percentage of disposable income has decreased to some extent in four of the G7 countries,2 compared with levels at the eve of the global financial crisis (see chart 1).

However, one area which is still a cause of growing concern is student debt. In the US, for example, student loan debt is the only form of consumer debt that has grown since 2008. Balances of student loans have eclipsed both vehicle loans and credit cards, making student loan debt the largest form of consumer debt other than mortgages.3

The situation is even worse in England. A recent report found that, according to multiple estimates, the average English student faces the highest levels of graduate debt of the 8 Anglophone countries surveyed (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland, US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand).4 The report suggests that English students graduate last year with higher average levels of debt (around US$64,000) than even the average graduate of a private for-profit US university (US$32,600),5 while Canada-based students left university in 2015 owing an average of just over US$21,700.

Since 1995, 14 of the OECD’s 25 member countries have implemented reforms on higher education tuition fees – most of which have led to an increase in the average level of these fees.6 The trickle-down effect of this is that it is increasingly difficult to send our children to higher education, without taking out a loan or using a substantial chunk of our savings.

All-in-all it’s an expensive business, yet remains popular: 17% of students who attend American colleges ranked in the world top 200 aren’t from the US.7 It has to be worth questioning whether these institutions provide value for money, given the debts accumulated and the broad nature of college courses: in the first year students tend to take courses from a variety of fields and only declare a major at the end of the first year or even during the second year.8

One way to avoid such a large financial commitment is to join the US military, which offers free college education.9 Otherwise you could look beyond borders and consider universities in a whole range of countries. Your kids don’t have to study in your local or home country: there is a wide range of cheaper options where courses are taught in English or another non-local language and the level of education is equal, if not better.

Universities in Ireland don’t generally charge fees to EU passport holders; nor do universities in Denmark or Sweden, who offer a large number of courses taught in English. The Netherlands was the pioneer of the non-Anglophone countries to teach courses entirely in English and fees start at US$2,230 a year, whilst German institutions (in all except two regions) charge between just US$170 and US$280 a year.10

On a cautionary note, there’s a little more to it than that. The figures I’ve used are the cheapest possible and to get a truer idea of what the fees will really cost, we’d need to delve further into factors such as type of course (medicine is often one of the most expensive undergraduate courses11), the university and its location. The last of these is important as there can be huge differences: institutions in Bavaria and Lower Saxony often charge between 4 and 6 times more than elsewhere in Germany; and whilst Brussels-based courses charge an already reasonable minimum of US$415, their Flemish equivalents’ lowest rate is just one US Dollar!

Possibly the largest discrepancy though, is in the UK. In England the legal maximum a university can charge an EU/EEA citizen for an undergraduate course is GBP9,000 (c. US$13,040) – and all but a handful do so.12 In Scotland the standard fee is GBP1,820 (c. US$2,640), which could be paid for by the Student Awards Agency for Scotland if your daughter or son qualifies for Scottish or other EU nationality and residency… unless they are categorised as an English resident, in which case you may have to pay GBP9,000 (c. US$13,040).13 Residency for this purpose is defined as “ordinarily resident in the EU, the EU overseas territories, elsewhere in the EEA or Switzerland for the three years immediately before the first day of the first academic year of the course” and nationality of an EU country means either the student or a family member.14

If students don’t meet the residency requirements, they can still qualify for funding if they were born in and have spent the greater part of their lives in the place they declare as home; or they (or a family member) are returning from temporary employment or study outside of that place. To get the full fee funding, you or your son/daughter may have to have lived previously in Scotland; otherwise you could qualify for the standard Scotland rate.

To qualify for local fees for universities in other EU/EEA nations15, the student must usually be a national of one of those countries.16 However, some European countries also allow the same rates to apply to someone who has lived in the EU for a certain period of time before applying for the study programme or holds a permanent residence permit in any EU country.

If your daughter/son doesn’t meet the EU/EEA criteria, fees are generally much higher in European universities; although there are exceptions in France and Germany and costs remain relatively low in Belgium (especially Flanders) and you may qualify for some kind of scholarship or financial assistance.

Unfortunately, it’s not purely about tuition fees: we also have to factor in the cost of living in general. Adding together an average spend on food, rent for a 1-bedroom apartment and a monthly public transport pass, shows us there’s quite a difference depending on where the university is located (see table).

The actual figures will of course differ according to individual spending patterns, but the table gives us some indication as to how much you’d need to fund your child through an undergraduate course. Greece comes out as a clear winner with many courses taught in English,17 zero fees for EU and just US$1,115 for non-EU citizens,18 plus average monthly living costs of around US$725.19

The numbers mentioned are just a rough idea of the potential costs involved. Having said that, I think they open the eyes to the possibilities of a value-for-money university education outside Thailand or your ‘home’ country.

If your children aren’t yet at university age yet, thinking about fees can be a useful reminder to put together a financial plan for the last years of their education. We all know it can be very costly and it’s vital to have some money set aside. Those student days will come sooner than you realise!

Footnotes:

1 http://www.ideaeconomics.org/

2 https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-debt.htm

3 https://www.newyorkfed.org/studentloandebt/index.html

4 http://www.suttontrust.com/researcharchive/degrees-of-debt/

5 idem

6 OECD (2011) How much do tertiary students pay and what public subsidies do they receive? p. 257, OECD, Paris.

7 https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/world-ranked-universities-most-international-students

8 http://www.internationalstudent.com/study-abroad/guide/uk-usa-education-system/

9 http://www.military.com/education/money-for-school/going-to-college-for-free-can-you-afford-not-to.html

10 www.studyineurope.eu

11 ibid

12 http://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/university-tuition-fees/reddin-survey-of-university-tuition-fees/foundation-undergraduate-tuition-fees-2015–16-ukeu/

13 http://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/university-tuition-fees/going-to-university-in-scotland/

14 http://www.saas.gov.uk/full_time/pg/eligibility.htm

15 EEA = EU countries, plus Iceland, Liechtenstein & Norway

16 http://www.studyineurope.eu/who-is-an-eu-student

17 www.bachelorsportal.eu/countries/25/greece.html

18 www.studyineurope.eu

19 Numbeo.com

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook: /MBMGGroup |