We tend to think of a concerto as a work for a lone soloist battling it out against a full orchestra and during the late romantic period this was a fairly accurate if stereotypical picture.

In the seventeenth century the word concerto was rather vague. It was originally used to describe more-or-less anything for voices with instrumental accompaniment. Later many such works were described as cantatas. During the baroque two types of concerto emerged and they existed pretty well side by side. One was the solo concerto for a single instrument and orchestra, and the other was the so-called concerto grosso or “big concerto”. The main feature of the big concerto was that it was conceived for two groups: a small group of soloists known as the concertino – literally the “little ensemble” – and the larger group often described as the ripieno. The concertino or soloists’ group predictably contained more virtuosic music than that of the ripieno.

Countless concerti grossi – to use the correct Italian plural – were churned out by baroque composers but the best-known were those of Corelli, Handel and Vivaldi. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos are mostly concerti grossi in all but name. Eventually the concerto grosso went the way of most things and by the 1750s had simply fallen out of fashion. It gave way to the solo concerto which so perfectly matched the romantic ideals of the century to come.

Like so many historical forms, the concerto grosso was revived in the twentieth century by composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Ernest Bloch, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Heitor Villa-Lobos who used various baroque ideas within a more modern musical language.

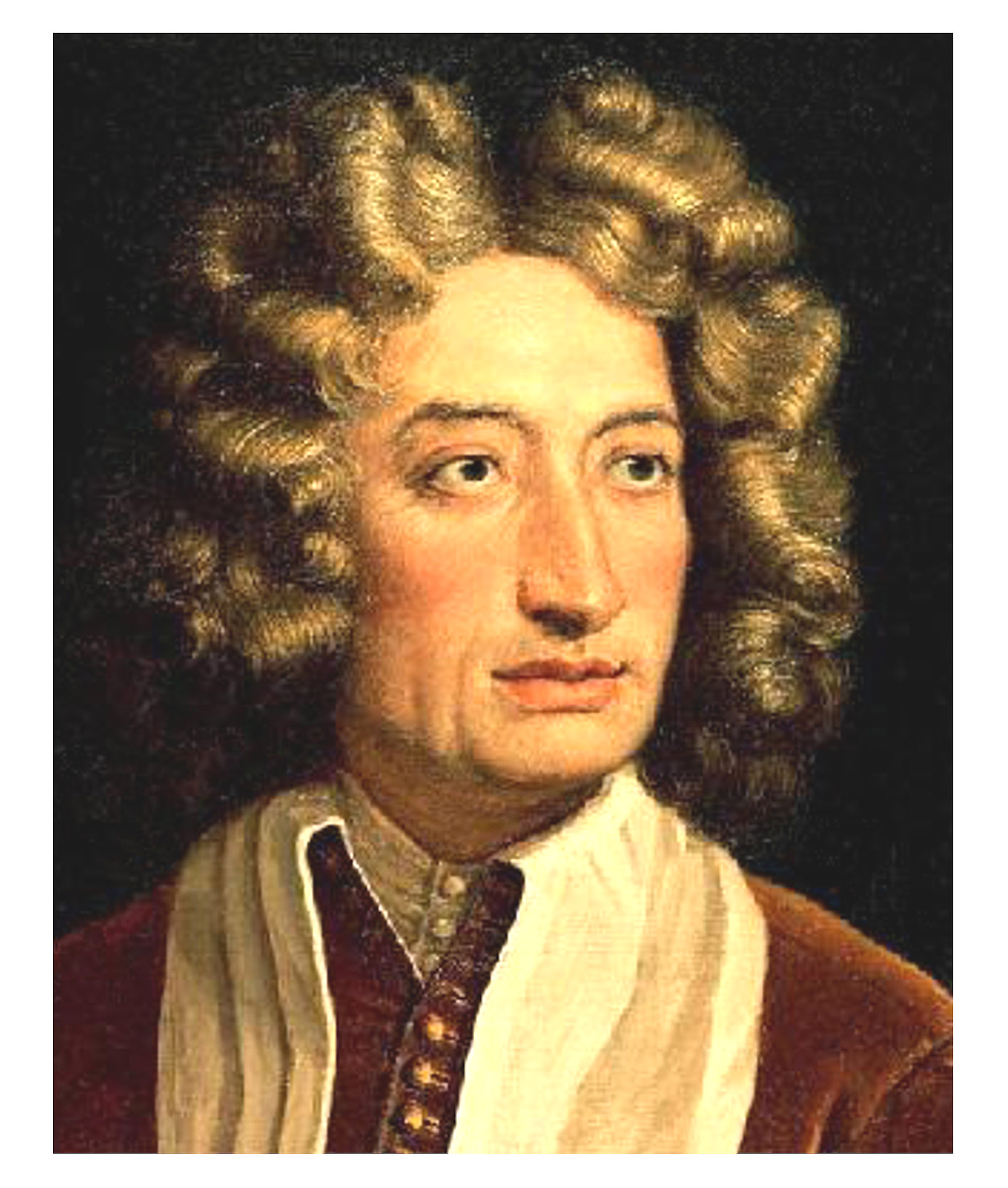

Arcangelo Corelli was the first important composer to use the description “concerto grosso” although the format of a small group contrasted against a larger one had been around for some years. He was a key figure in baroque music and one of the most influential violinists of all time. His twelve concerti grossi were published in Amsterdam in 1714 and their influence was enormous.

Although considered a fine violinist, Corelli never ventured above the note D on the highest string. By today’s standards that is conservative indeed. This C minor concerto follows the conventional pattern of slow-fast-slow-fast-fast and each movement becomes progressively longer. The concertino group consists of just two violins and cello. There’s a typical declamatory opening that leads into a quicker movement. The following slow movement is rich in harmony although it must have sounded quite progressive at the time. The vivace movement is vivacious indeed and so is the scurrying finale but sadly some of the detail in the fast passages is almost lost in the cavernous acoustic of the church.

Fast-forward twenty years and we find something quite different. Handel wrote a couple of dozen concerti grossi, nearly all of which are found in two sets: the Opus 3 and the Opus 6. The earlier set was compiled in 1734 by a London publisher simply by cobbling together various bits and pieces of Handel’s music together without the composer’s involvement or even his permission. In those days they could get away with that sort of thing. The Opus 6 collection consists of twelve concertos that Handel had written specifically as a coherent set during 1739.

Like the Corelli, they’re scored for a concertino group of two violins and cello and a string orchestra with harpsichord continuo. The overall pattern is pretty similar to that of Corelli’s as well but there the similarity ends. Handel brings to the music a huge variety of musical styles and these concerti and are generally considered to be amongst the finest examples of the genre.

Incidentally this is a charming performance too from students at The Colburn Young Artists Academy in Los Angeles. There’s some fine string playing, lovely ensemble contrast and a careful observation of dynamics. There are a couple of moments when the tempo feels slightly insecure but considering they are playing without a conductor I certainly won’t hold that against them.

The first short movement starts dramatically and leads into a lively fast movement. The third is slow and dignified in which the violin soloists build phrases in imitation with some lovely harmonies. The lively fourth movement sounds as though it’s going to be a fugue but instead turns into a delightful episodic movement with some jolly tunes and a few musical surprises too. The dance-like final movement (at 08:22) uses a great deal of spirited imitation in which at times the soloists echo phrases played by the full orchestra, revealing Handel at his light-hearted best.

|

|

|