Washington (AP) – Bacteria live on everyone’s skin, and new research shows some friendly germs produce natural antibiotics that ward off their disease-causing cousins. Now scientists are mixing the good bugs into lotions in hopes of spreading protection.

In one early test, those customized creams guarded five patients with a kind of itchy eczema against risky bacteria that were gathering on their cracked skin, researchers reported Wednesday.

“It’s boosting the body’s overall immune defenses,” said Dr. Richard Gallo, dermatology chairman at the University of California, San Diego, who is leading the work.

We share our bodies with trillions of microbes that live on our skin, in our noses, in the gut. This community – what scientists call the microbiome – plays critical roles in whether we stay healthy or become more vulnerable to various diseases. Learning what makes a healthy microbiome is a huge field of research, and already scientists are altering gut bacteria to fight diarrhea-causing infections.

Wednesday’s research sheds new light on the skin’s microbiome – suggesting that one day it may be possible to restore the right balance of good bugs to treat skin disorders, too.

“It’s a really important paper,” said Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, who wasn’t involved with the new research. “It does open a window for a potential new treatment.”

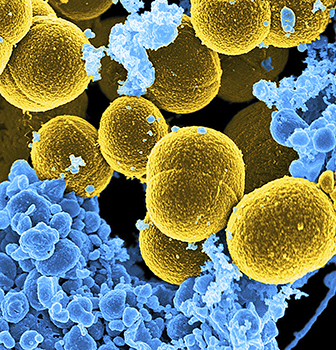

Healthy skin harbors a different mix of bacteria than skin damaged by disorders such as atopic dermatitis, the most common form of eczema. Those patches of dry, red, itchy skin are at increased risk of infections, particularly from a worrisome germ known as Staphylococcus aureus.

Gallo’s team took a closer look at how microbes in healthy skin might be keeping that bad staph in check.

They discovered certain strains of some protective bacteria secrete two “antimicrobial peptides,” a type of natural antibiotic. In lab tests and on the surface of animal skin, those substances could selectively kill Staph aureus, and even a drug-resistant strain known as MRSA, without killing neighboring bacteria like regular antibiotics do, the team reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

But those good bugs are rare in the skin of people with atopic dermatitis, Gallo said.

“People with this type of eczema, for some reason that’s not quite known yet, have a lot of bacteria on the skin but it’s the wrong type of bacteria. They’re not producing the antimicrobials they need,” he explained.

Would replenishing the good bugs help? “They’re normal skin bacteria, so we knew they would be safe,” Gallo noted.

His team tested five volunteers with atopic dermatitis who had Staph aureus growing on their skin’s surface – what’s called colonization – but didn’t have an infection. Researchers culled some of the rare protective bacteria from the volunteers’ skin, grew a larger supply and mixed a dose into an over-the-counter moisturizer. Volunteers had the doctored lotion slathered onto one arm and regular moisturizer on the other.

A day later, much of the staph on the treated arms was killed – and in two cases, it was wiped out – compared to the untreated arms, Gallo said.

“We’re encouraged that we see the Staph aureus, which we know makes the disease worse, go away,” he said.

The study couldn’t address the bigger question of whether exposure to the right mix of protective bacteria might improve atopic dermatitis itself, cautioned Mount Sinai’s Guttman-Yassky.

Next-step clinical trials are underway to start testing effects of longer-term use.