Following on from a piece my business partner, Paul Gambles, penned for The Nation recently, people keep asking us about how best we can understand the state of modern capitalism, and whether the cocktail of protest, social unrest, and financial scandal (etc.) are taking us any further along the road to some kind of ‘event’.

Talking to CNBC’s Patricia Szarvas recently, she asked Paul how repeating the mistakes of 1930s today could ever lead us to blunder into war again. He explained how social discontent is often a breeding ground for geo-political tensions. As a result, he wrote the following guest blog piece for CNBC.

There is a saying that, “To a man with a hammer, everything apparently looks like a nail.”

Karl Marx’s hammer was economic input in all its forms (primarily capital – i.e. money, surplus capital – i.e. profit, and above all labour).

As a result of this obsession, Marxian economic theories tended to start and finish with inputs of some form, invariably labour.

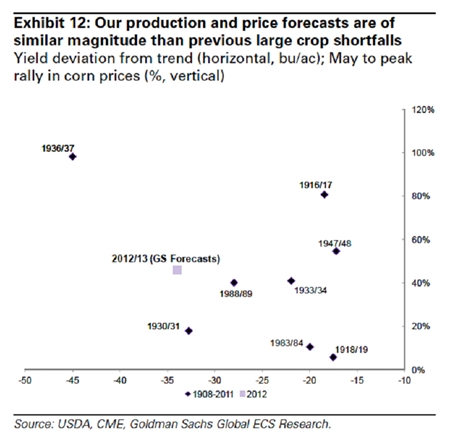

Source: Goldman Sachs, August 2012

Source: Goldman Sachs, August 2012

This tendency so irritated Eugen Bohm-Bawerk that when the bearded German socialist philosopher had been laid to rest in Highgate Cemetery, Bohm-Bawerk got this off his chest in a very tetchy pamphlet (Karl Marx and the Close of His System).

If it had been intended as a cathartic piece it failed miserably. Herr Bohm-Bawerk’s rather emotive conclusion was that despite having demonstrated all the shortcomings of Marxian theories, Karl Marx would still secure permanent fame just like Hegel (who also annoyed Herr Bohm-Bawerk intensely):

“The theoretical work of each was a most ingeniously conceived structure, built up by a magical power of combination, of numerous storeys of thought, held together by a marvelous mental grasp, but – a house of cards.”

At this point, perhaps Herr Bohm-Bawerk should have spent sometime in the company of Dr. Freud.

The pamphlet acknowledged that Marx and his economic theories owed a great deal to the earlier pioneering work of Adam Smith. Smith’s fate has subsequently become inexorably intertwined with that of Marx: their seminal works are read nowhere near as widely as they should be. Marx has a political schema named after him by left wing extremists and Smith has a right wing politicized think-tank. Neither of these accurately reflect the beliefs of their eponymous heroes.

This is especially ironic as the system identified by Smith (capitalism) has generally come to be seen as diametrically (and dialectically) opposed to Marxism. The truth, as ever, is rather more complex.

Capitalism’s adherents believe that an inherent form of socio-economic Darwinism will always enable the system to evolve to something stronger and better by making the most logical choices about deployment of capital, which drives all other decisions. Not so much an ‘invisible hand’ as a whole invisible Mexican Wave.

Despite the credit crunch, the GFC, Lehman’s collapse and the ‘Lie-bore’ allegations, capitalism’s advocates see it as such an inherently efficient system that, by its own processes, it makes itself stronger and more efficient every day. An example of this blind faith can be found in Professor Victor Lippit’s book Capitalism:

“Capitalism continually renews and re-invents itself. This helps us to understand the fact that despite its severe internal contradictions, contradictions that Marx anticipated would bring about the ultimate collapse of capitalism, the capitalist system has managed to remain vibrant over the centuries.”

Both Smith and Marx warned that too great an imbalance between the suppliers of capital and the suppliers of labour could destroy the foundations of democratic capitalism – the difference being that Smith wanted to avert this while Marx agitated to bring it about. Occupy Wall Street (OWS), in its rare moments of coherence, came close to linking these imbalances with the venality of politicians, bankers and, by extension, the so-called 1%.

Both income and wealth have, much to the chagrin of OWS, become ever more concentrated: American salaries have stagnated for 40 years whereas corporate profits climbed to dizzying, barely sustainable heights.

Record amounts of income have been transferred from employees to business shareholders.

In developed markets, Small Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) are increasingly deprived of access to capital while Multi-National Corporations (MNCs) and public companies hold record levels of cash and have unprecedented access to debt and equity capital.

The biggest transfer mechanism of all remains the Euro – the single currency that in its relatively short lifespan has facilitated enormous transfer of wealth to the core nations, primarily Germany and the transfer of debt to the peripheral nations, the GIPSIs of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy.

The most widely recognized measurement of income distribution (the Gini co-efficient) is at extreme levels in developed and developing markets.

These are all symptoms of a socio-economic structure at breaking point – where social tensions could quickly spiral out of control so dramatically that the imbalance between the suppliers of capital and the suppliers of labour could destroy the whole system.

These symptoms are visible everyday from the protest movements of Jasmine Riots, impoverished GIPSIs and Arab Springs (now into its second year), to violently enforced regime changes to the widespread resentment of ‘highly-paid privileged bankers’ or anyone else whose ‘scapegoating’ or culpability can be offered to the masses as a way of exonerating our political leaders despite their hands looking equally dirty.

That is not to say that these symptoms will inevitably erupt into full-blown contagion. Maybe OWS’ inability to formulate a cogent message and strategy will simply see the resumption of widespread complacency among ‘we the global people’. But the very existence of protest movements should be a warning. We would not be the first generation to totally stuff things up and then have to look back ruefully on what we had destroyed.

“We did not realize how fragile our civilization was” – Friedrich Von Hayek in the years following WW I.

We don’t seem to realize how fragile our civilization is in 2012 either.

Perception, in this instance, is much more important than objective reality. A recent study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation showed that 25 percent of the UK population is living below the standard that they see as acceptable. This may be riddled with methodological flaws and questionable assumptions but I don’t fancy the chances of debating that with 15 million people if they take to the streets armed with pitchforks, as unlikely as that might seem today.

All of this is backed up by Jeremy Grantham’s latest Quarterly Report where he asks if we are entering a long term and politically dangerous food crisis. Grantham believes that we are five years into a severe global food crisis that is very unlikely to go away in a hurry. It threatens poor countries with increased malnutrition and starvation, even collapse.

Resource squabbles and waves of food induced migration will definitely threaten global stability and global growth. Grantham believes that this threat is badly underestimated by almost everybody and all institutions with the possible exception of some military establishments.

The extent of the most recent shock to the system is captured in a chart from Goldman Sachs. It provides the most recent update on the deteriorating US corn situation. The vertical axis shows how much prices have surged since May to a given year’s peak rally. The horizontal axis shows crop yield deviation from historical trends. At the time it was created, it was not even August, and the 2012 crop yield had already sailed past almost every other record-deviating year. While it has a ways to go before it leaves what one might call “the known yield-deviation universe” by surpassing the ‘36 crop, there is still more room to run.

Please read Jeremy Grantham’s quarterly letter for the full report but the executive summary is that the current weather driven spike in US corn prices may only be the tip of the iceberg. It may be that we are about five years into a chronic food crisis that is unlikely to fade for any decades (yes decades!) or at least until the global population has considerably declined from its peak of over nine billion in 2050.

I have no political axes to grind whatsoever. I equally distrust politicians of every stripe. But I do worry that unless we do something to ensure greater perceived inclusion of the rapidly growing body of those who see themselves as economically disenfranchised then we might look back, like Von Hayek, too late and lament what we have lost.

More balance might be needed if the warnings of the student, Karl Marx, are not to destroy the democratic capitalist system of his mentor, Adam Smith.

| The above data and research was compiled from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither MBMG International Ltd nor its officers can accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the above article nor bear any responsibility for any losses achieved as a result of any actions taken or not taken as a consequence of reading the above article. For more information please contact Graham Macdonald on [email protected] |