Gustave Le Gray is not such a well known name as Daguerre, Nadar and Cartier-Bresson (mentioned a few weeks back). Some might even say he is forgotten, but not so. His work and what he accomplished and how he did it has definitely lived on after him. One of my favorite tomes is entitled “Techniques of the World’s Great Photographers” and Gustave Le Gray is awarded six times the space in the book compared to that given to Daguerre. He was not forgotten by that book publisher in 1981.

Le Gray is remembered, amongst many reasons, for the technique of “patching”. This is a way of ending up with a very pleasing photograph, by introducing new elements. This is similar to the still current techniques of dodging and burning, so a brief word on these first will not go astray; however, Le Gray’s technique is actually the forerunner of today’s ‘photoshopping’.

Back to dodging and burning. When a “hand” print was made, the technician controlled the intensity of light falling on the sensitized photographic paper after it came through the negative. In any negative, there will be areas that the photographer would like to see made a little darker, or lighter. Very often the sky lacks a little detail, so the technician will be told to “burn in” the sky and “dodge” the foreground. So while making the exposure of the photographic paper, the technician will give the sky area more exposure time (burning in), while holding back the foreground (dodging).

The end result of this technique is a scene with an “interesting” cloudy sky, rather than just a pale washed out one. So it is “enhancing” the print a little, but this is not photo fudging – the interesting sky was there to begin with, it is just that with the standard printing process you lose the clouds if you keep the foreground shadow details. The problem is the sensitivity of the film and paper, but the selective technique does get over this. This is not photoshopping.

Now pity poor old Gustave Le Gray. In the early 1850’s the negatives themselves were so insensitive that to get a negative which would show any details in the foreground subject(s), the skies were totally overexposed, so there was absolutely no cloud detail at all. You could dodge and burn as much as you liked – if it wasn’t on the negative to begin with, it would never appear on the final print. (This is why you should err on the side of overexposure, rather than underexposure. This was one of my early lessons in photography. If it is on the negative, you can reproduce it.)

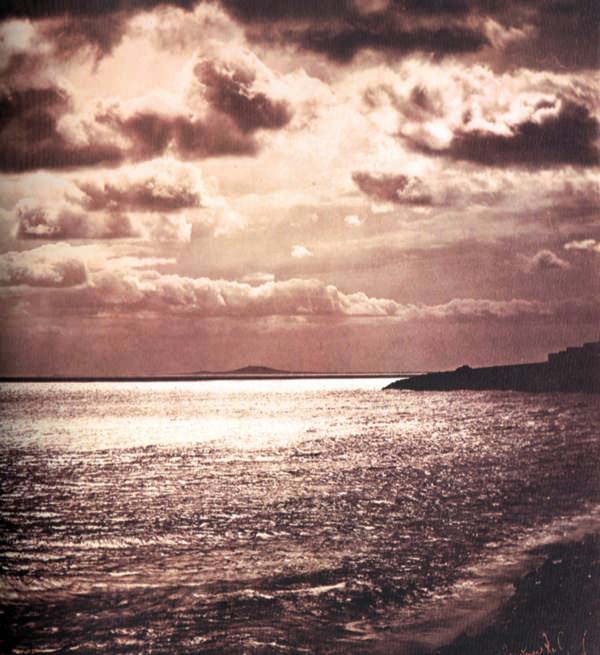

However, Gustave Le Gray produced prints like the one with this week’s article, (which was exhibited in London in 1856). Superb seascape with details in the foreground and ominous skies with plenty of detail. How did he do this? The answer was a technique that Le Gray developed called “patching”. With his insensitive negative there was no sky detail, so what Gustave Le Gray did was to make exposures of “interesting” skies alone, and then doubly expose the print. One exposure was for the foreground, using its own negative, and the second exposure was for the sky, using the special “sky” negative.

This worked very well, as you can see with this week’s photograph, and you can see why Gustave Le Gray chose seascapes to do this with. Confused? Don’t be. The horizon line with seascapes is flat and well defined, so he could easily blank off the top and expose the sea foreground, then blank off the bottom of the print and expose for the second negative producing the clouds and sky. It is still possible to “marry’ two sections together, but the more convoluted the join, the harder it gets, that is why the seascape concept worked so well.

On course, today we can get computer programs to do this for us such as the ubiquitous Photoshop, but do not forget Gustave Le Gray – he did it first! And the Photoshop principle is exactly the same.

|

|

|