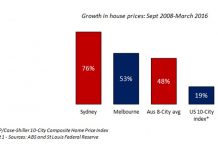

As asset allocators, one of the most important debates we have is our view on inflation, disinflation and deflation. The reason is really very simple, as getting this call right largely determines whether one makes positive or negative returns for investors. So, on that subject, I thought I would share some of the insights of MitonOptimal.

So far this year, the press has been inundated with stories on rising inflation; just to put this into perspective, Joanne Baynham of MitonOptimal did a Google search recently and asked to see all the stories on inflation over the past month alone and the number of hits was four hundred and thirty five million, contrast this with the same search on deflation and the number was a little over one million. Clearly the world is worried and with food prices going sky high, it is not hard to see why. But whilst rising food prices affect everyone and the poor especially, one needs to step back and ask whether these increases will lead to more permanent inflation, or if these are temporary in nature.

Illustration 1

Illustration 1

On that subject our view is that it depends where you are living in the world, to determine the “stickiness” of inflation. In the developed world, at the moment, it is hard to see inflation running away, especially when consumers are still so highly indebted, unemployment remains high and the output gap is still large. But at the same time, we do see prices rising – not falling – going forward, as growth continues to be upgraded, output gaps narrow and companies find themselves with more pricing power. Germany is an excellent example of this, with inflation consistently higher than expected and wage inflation starting to bite thanks to strong export growth with Asia.

The UK is another such example with inflation coming in at 4% in mid/late February, way above the target of 2%, but in the case of the UK it is hard to see this becoming entrenched, as wage inflation remains anaemic, house prices are stagnating (a good proxy for consumer confidence) and a government determined to cut back on fiscal spending. The US is similar to the UK, in the sense that headline inflation might be rising, but not core inflation, and once again the labour market being slack in that economy is helping to keep inflation expectations under control.

In the emerging world, inflation has a far greater chance of becoming more permanent. Higher food prices have a far greater impact on inflation as they are a much larger component of the CPI basket and companies have less slack and hence more pricing power to pass increases on to the consumer. The tricky aspect of inflation in emerging markets (EM) is to establish whether commodity prices are going up because of supply or demand issues, but given the actions of central bankers in the EM, one would have to conclude that they are more concerned about demand leading to higher commodity prices, otherwise they would not be so intent on rising interest rates and reserve requirements for their banks.

So on balance where does that leave us? In the opinion of MitonOptimal, based on the fact that core inflation remains relatively contained and slowly rising in the developing markets (DM), they continue to be overweight equities and underweight bonds. But there will be a point when fears over higher inflation lead to concerns about higher interest rates and this tends to lead equities markets lower. However, they do not believe there is cause for concern yet. The FT recently noted that CPI at 4% could be the line in the sand, as this has traditionally been the point where equity markets have sold off. US consumer prices have risen above 4% fourteen times since 1927 and on every occasion except one, markets have fallen by 5% and sometimes even more. In the EM region they see inflation going higher still and hence are underweight equities and bonds, given concerns about rising interest rates in this region and the fact that real rates remain negative in many EM markets.

Given all of this you can see that market timing is vital and being in multi-asset, multi-managed funds which are liquid is equally as important.

New York Times best-selling financial writer John Mauldin recently wrote a piece entitled “Some Thoughts on Market Timing”. While Mauldin, like ourselves, believes in long term themes and is not a short term market timer he highlights the need to identify major trends. Mauldin refers to the work of the team at Sentiment Traders who distinguish between “smart and dumb money”.

Illustration 2

Illustration 2

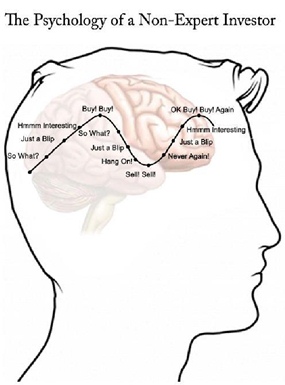

We would never be so judgmental but we believe that too many investors fail to diversify adequately and fail to adjust their portfolio allocation according to changing economic conditions. A totally passive portfolio will be wrongly aligned for significant parts of the economic cycle, only producing optional performance when the lucky coincidence of economic conditions line up with the bought and held portfolio.

We believe that this is because most investors are better at recognising opportunity than risk and, therefore, are great buyers but sometimes lack an exit strategy to sell – the most successful investors know where the entrance and exit is for any asset they buy.

That doesn’t mean that we condone day trading. This is only for the brave and skilled investors. Time and again the proof is that trading with too short term a focus fails to allow enough exposure to the potential trends and incurs too high costs. However, adaptive asset allocation means identifying medium to long term trends – typically 18 months or longer but reflecting the ever changing investment landscape in an ever evolving portfolio allocation decisions – or as Lord Keynes said, “ Sir, where the facts change, I change my mind – what do you do?”

Even more dangerous is whimsical changing of trends, after the event – last year we wrote about non-expert investor psychology. (See the illustration 1)

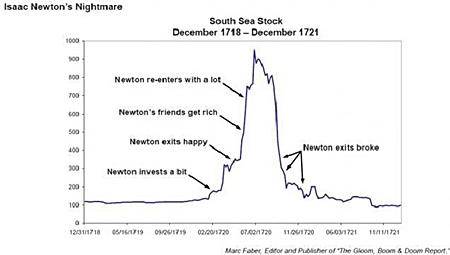

Maybe the best historical example of this is Sir Isaac Newton and the South Sea Bubble. Newton sold his £7,000 of stock for a 100% profit but re-entered the market at the top, losing £20,000 and lamenting, “I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies but not the madness of people.”

The best recent example is probably Sean Quinn and the well-publicised near collapse of the Anglo Irish Bank, which wiped out at least €1 billion of the family’s wealth. It is widely believed that the Quinn Family had acquired up a 25% stake, mainly through contracts for difference. Quinn had continued to buy stock as the share price fell but his averaging in strategy proved useless when the bank had to be nationalized by the Irish government to prevent complete collapse.

If you are not confident on making decisions yourself or, even if you are but need a sounding board then the following may help:

* Investment Professionals take the emotions out of the decision making process of trading.

* It is not only about finding the right asset class but knowing when to get in, looking for any changes in fundamentals that would change the outlook for the asset and, finally most important of all, knowing when to get out.

* Many people will get in to something (buy) quite quickly or easily but it is the selling that is the hardest decision to make and the most critical as the average person tends to sell either way too early or much too late.

* Now with unprecedented QE2 and global financial crisis skewing markets around the world making even old timing indicators less relevant, it is even more imperative to leave it to the experts.

The above data and research was compiled from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither MBMG International Ltd nor its officers can accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the above article nor bear any responsibility for any losses achieved as a result of any actions taken or not taken as a consequence of reading the above article. For more information please contact Graham Macdonald on [email protected]