The Band: Music From Big Pink (Capitol)

People were dizzy, they needed an antidote. You can only take so much of psychedelic acid rock before you either lose it or turn into a turnip. All them drum solos and lightshows and guitars swirling around the room turning reality into distorted visions that made your brain hurt. People were getting homesick.

Bob Dylan was the first man jumping the ship when he broke the silence after a year and a half and delivered a quiet, simplistic and quite enigmatic set of songs with dirt under their nails on “John Wesley Harding”. The Beatles put their foot down with “Lady Madonna”, as did The Rolling Stones with “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”. Time to sober up.

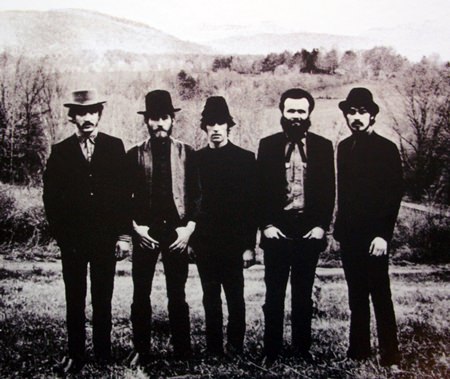

So times were changing. Nevertheless, “Music From Big Pink” came as a revelation when it arrived in July 1968. No studio tricks, no backwards guitars, no interstellar overdrives, just a plain and simple record consisting of songs about basic values performed by a collective of musicians who loved each other’s company and who treated each song, every note they played, with love and awe. The black and white photograph on the sleeve could have been taken during the American Civil War. Or right after. They looked like men from the mountains, men of soil – so distant from Carnaby Street that they probably had travelled through time.

The record buyers reacted slower than the contemporary musicians as The Band received instant god like status among them while the record was a sleeper, entering the Billboard charts in August ’68 and climbing reluctantly to its peak at #30. In England the album didn’t chart at all. And still, that very album allegedly convinced Eric Clapton that Cream was a dead end. And George Harrison was so enchanted by their Musketeers like closeness and mutual respect for each other when he met them that he wanted to quit the Beatles. No egos, just music and a common feeling of affiliation.

“Music From Big Pink” was in many ways a back to the future, the beginning of roots music, an album that spoke to its time through visions from a rich tradition and period in American history (the Civil War is the central pillar of the structure), sometimes using biblical expressions. The album focuses on the collective rather than the soloist.

The Band’s members were so musically versatile that they could switch around on instruments and all could sing, except the Gyro Gearloose of the organ, Garth Hudson, the keyboard wizard who had to tell his mother that he was their piano teacher to be allowed to play and tour with them.

The album is a homogenous whole, the songs are organic, they seem untouched by technology, and when the music flows into your living room – it’s as if you are actually sitting among the musicians while they play. The songs tell their stories without egomaniac interruptions of any kind. These guys play for and with each other with a common goal and total focus on the song, words and music are one.

Bob Dylan wrote three of the 11 tracks, two of them respectively with Richard Manuel (“Tears Of Rage”) and Rick Danko (“This Wheel’s On Fire”), while the third, the album’s redemptive, religious and very uplifting finale, “I Shall Be Released” is his alone. Three excerpts from the summer of 1967 when Dylan and The Band made the legendary demos which later became known as “The Basement Tapes”.

However the album’s central track is “The Weight”, an enigmatic story with a strong, rolling backbeat and a sprinkle of gospel woven into a chorus that touches the heavens. It’s impossible to get tired of “The Weight”. Every listen is gratifying. Even now, 45 years later.

The album was conceived at a time when The Band was a real collective in every meaning of the word, even when it came to writing songs. Robbie Robertson does not carry the load alone, they all participate and deliver.

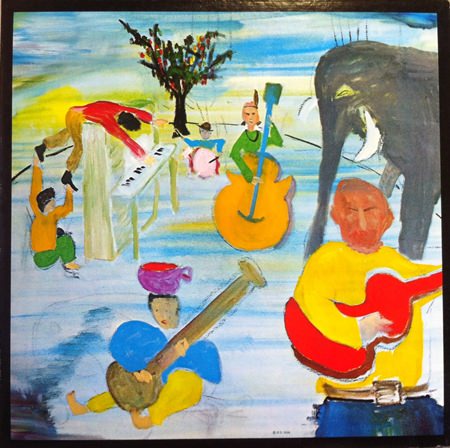

Bob Dylan did the humorous cover painting. It is him in the red sweater being pushed over the piano by Garth Hudson. The elephant and the sitar do not participate in the recording but could be a snide dig at The Beatles and songs like Traffic’s “Hole In My Shoe”.

I won’t say that “Music For Big Pink” saved rock, but it did show that there were other paths to walk, and it sure reclaimed some of what was being lost in the drugged out mumbo jumbo of psychedelia. The Band took you by the arm and said, Hey, this is what it should be about: music and words that touch your soul.

Levon Helm, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel have all left us. But their voices and their playing remain. On “Music For Big Pink” they shine forever.

Released: July 1968

Produced by: John Simon

Side One

1. “Tears of Rage” (Dylan/Manuel) 5:23

2. “To Kingdom Come” (Robertson) 3:22

3. “In a Station” (Manuel) 3:34

4. “Caledonia Mission” (Robertson) 2:59

5. “The Weight” (Robertson) 4:34

Side Two

6. “We Can Talk” (Manuel) 3:06

7. “Long Black Veil” (Wilkin/Dill) 3:06

8. “Chest Fever” (Robertson) 5:18

9. “Lonesome Suzie” (Manuel) 4:04

10. “This Wheel’s on Fire” (Dylan/Danko) 3:14

11. “I Shall Be Released” (Dylan) 3:19

Personnel:

Rick Danko — bass guitar, fiddle, vocals

Levon Helm — drums, tambourine, vocals

Garth Hudson — electronic organ, piano, clavinet, soprano and tenor saxophone

Richard Manuel — piano, organ, drums, vocals

Robbie Robertson — electric and acoustic guitars, vocals

Additional Personnel:

John Simon — producer, baritone horn, tenor saxophone, piano

Don Hahn — engineer

Tony May — engineer

Shelly Yakus — engineer

Bob Dylan — cover painting

Elliott Landy — photography

|

|

|