Back in the days when I was a music teacher at a school in London, I was regularly asked by students and parents, “How long does it take to play the violin?” (or the cello, the trombone or whatever). It’s rather like asking how long it takes to learn a foreign language. You see, it all depends on several variables: how intelligent you are, whether you have a natural aptitude for the subject, how many hours you are prepared to spend in study and how good you want to become. Take a foreign language for example. If you want to have a smattering of the language to get around, you could possibly learn enough within a month or two. If on the other hand, you want to be reasonably fluent, you’d need a great deal longer and intensive immersion in the target language. It’s the same with music.

If you’d never touched a piano in your life and you wanted to play “Twinkle, twinkle Little Star” with one finger, I could teach you the notes within twenty minutes – even less if you are a fast learner. There would, of course be a modest fee. But if you wanted to be a top-class classical pianist, we’re talking about many years of study. You’d also need a professional teacher. The bowed stringed instruments are often considered the most challenging. Violinist and teacher Sue Hunt claims that playing the violin is “the most complicated activity” known to humankind. It’s one of the reasons that top players start young.

The Japanese teacher Shinichi Suzuki pioneered the notion that given the right musical environment, infants could learn to play the violin if the learning steps and the instrument were small enough. Some of his beginners were just two years old. This is unusually early and many string teachers consider the ideal age to be between three and five. However, an overwhelming passion to learn the instrument and the ability to concentrate are probably more important than the physical age.

But not everyone wants to be a professional orchestral player. Some people want to play an instrument just for the fun of it. If you’re the wrong side of fifty and you really want to try learning an instrument, then go for it. It’s a wonderful hobby and in some countries there are bands and orchestras for adult beginners. Even playing at beginner level can bring enormous satisfaction and a sense of self-esteem and I’d recommend it to anyone with the motivation to give it a go.

All this talk about learning reminds me of my own musical studies which also included learning the cello. Here are two works which are encountered by every advanced student cellist at some point. They both have their technical challenges but they are tremendously rewarding to perform.

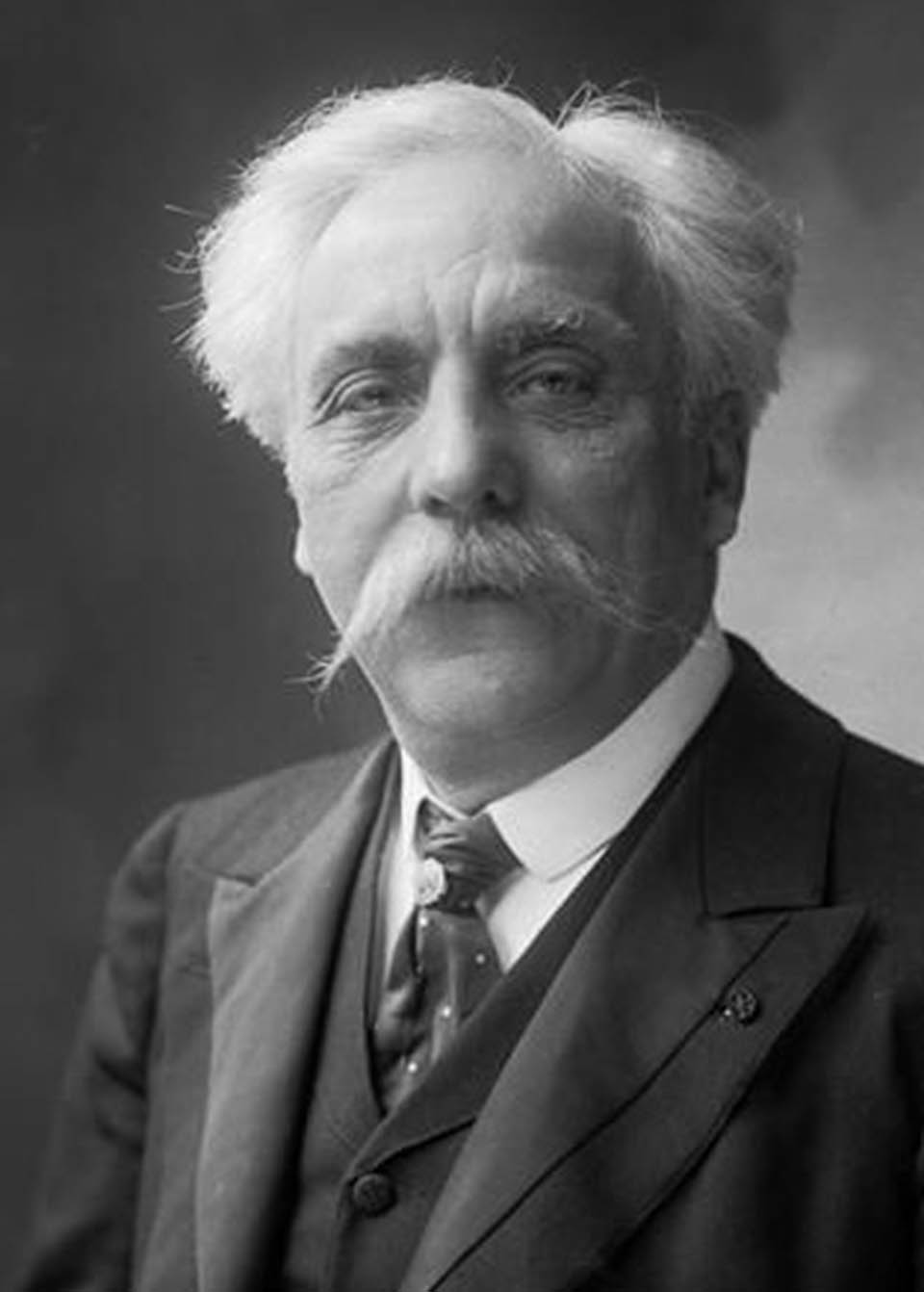

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924): Élégie for cello and orchestra Op. 24. Anna Grondalska (vlc), Szymanowski School of Music Symphony Orchestra cond. Marcin Grabosz (Duration: 07:21; Video: 720p HD)

Fauré (FOR-ray) is today perhaps best-known for his Requiem and was one of the foremost French composers of his generation. In 1880, having just completed his First Piano Quartet, Fauré began work on a cello sonata and in his usual manner, started writing the slow movement first. For some reason the rest of the sonata was never completed and in 1883 the slow movement was published as a stand-alone piece called Élégie. The first performance was such a great success that the conductor Édouard Colonne asked Fauré to write an arrangement for cello and orchestra. The arrangement was premiered in 1901; the legendary Pablo Casals was soloist and the composer conducted. This fine performance given by young musicians from Wroclaw in Poland has excellent audio quality and you can clearly hear the expressive counter-melodies in the woodwind.

Max Bruch (1838-1920): Kol Nidrei for Cello and Orchestra, Op.47. Ivan Karizna (cello), Frankfurt Radio Symphony cond. Christoph Eschenbach (Duration: 12:28; Video: 2160p HD 4K)

Bruch wrote Kol Nidrei in 1880 shortly after he took up the post of Principal Conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic on a three-year contract. The work was composed specifically for Liverpool’s Jewish community and it’s based on two Hebrew melodies, the first which is first heard on the solo cello and comes from the traditional service on the night of Yom Kippur. The title means “all vows” in Aramaic, which was one of the most common languages found in first-century Palestine. This evocative music shows Bruch at his best, with lovely melodies sumptuously harmonized. Although Bruch wasn’t Jewish himself, he really seems to have caught the essence of the Jewish spirit in this delightful music.

|

|

|