When you come to think about it, Western music notation is quite amazing because it has served musicians pretty well unchanged for several hundred years.

The orchestral music behind the latest blockbuster movie was written using virtually the same notation system used by Bach, Handel and Vivaldi. It’s international too, and a child learning the violin in Glasgow uses the same system as a professional player in Moscow. The music may be simpler but the “language” is the same.

Even so, music notation has its shortcomings. It can’t tell you exactly how loudly or quietly a piece should be played. It can’t tell you exactly how a phrase should be performed or exactly how to apply colour or vibrato to notes. Although the metronome appeared in 1868, not everyone bothered to use it. In the past, composers were often imprecise about what they wanted and wrote something like “a bit louder” or “a bit slower” which is vague to say the least. You might be surprised to know that even today these directions are usually written in Italian. The custom began several hundred years ago and the habit just stuck.

Because of the limitations of notation, a great deal of musical decision-making is left to the performer and one of the most challenging tasks is not actually playing the notes but deciding how to play them. In the case of an orchestra, someone has to make unilateral decisions and this is the role of the conductor. In a big orchestra individual musicians can’t always hear each other, so as well as beating time (which is not always done when the beat is obvious), the conductor has to give cues, control the overall orchestral balance and bring some meaning to the music.

At an orchestral concert you may be surprised that sometimes the conductor doesn’t seem to do very much work. This is because the work has already been done, sometimes weeks, days or hours before the concert. The conductor Leopold Stokowski was fond of saying that music notation is not music; it’s just “black marks on white paper. It’s the job of the performer to convert the black marks into living sounds.”

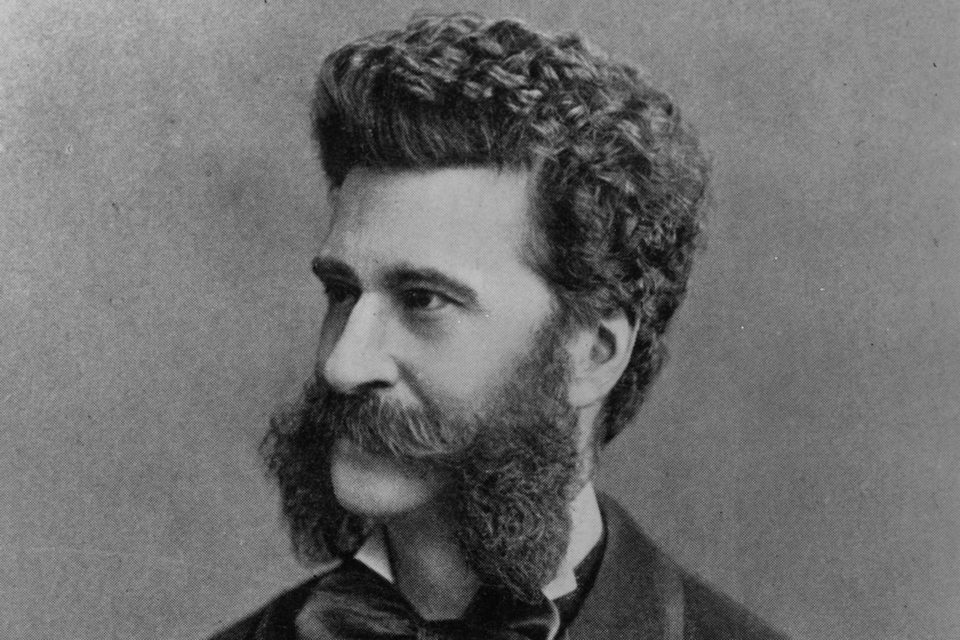

Carlos Kleiber (1930-2004) was one of the less well-known great conductors of the twentieth century, perhaps because in his entire professional life he gave less than a hundred concerts and only about four hundred opera performances. He made comparatively few recordings and refused to give interviews.

Even if you don’t know the opera Die Fledermaus (“The Bat”) you may recognise some of the tunes in the overture. This film was made in 1970 with the South German Radio Orchestra, and a dour-looking no-nonsense bunch they seem too. That’s until Kleiber works his magic with his fast thinking, fertile imagination, quirky sense of humour and his meticulous attention to detail.

Perhaps the most persuasive feature of the rehearsal – and indeed the most moving, is how these grim-looking orchestral players gradually warm to the conductor’s personality, his obvious expertise and his delight in the music. Some of them eventually start smiling and by the end you can even sense a shared feeling of joy. But not only that, if you watch all the way through – and it is really is worth finding the time – you can hear the remarkable transformation in the music from rehearsal to performance.

This piece was originally conceived as a ballet and was first performed over a hundred years ago, but the outrageous nature of the music and the choreography caused a near-riot among the Parisian audience. It’s a challenge to perform and for decades the work was considered virtually impossible to play by all but the best orchestras.

The International Orchestral Academy of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival was founded in Northern Germany by Leonard Bernstein in 1987. Each year the Academy assembles a youth orchestra from more than 1,500 applicants world-wide. Only 120 instrumental players – all under twenty-six years of age – are selected.

This film was made in 1988 and it’s fascinating to watch a legendary musician working so comfortably with such a young orchestra. I remember hearing a record of The Rite of Spring for the first time when I was about fourteen. It was the most exciting music I had ever heard. On reflection, perhaps it still is. Incidentally, when I was a music student in the 1960s, I once spoke to Stravinsky on the phone, because I wanted to arrange an interview while he was in London. The Great Man had a cold and was in a very tetchy mood, and in his squeaky voice and almost impenetrable Russian accent he told me, more or less, to sod off.

|

|

|