If you were brought up in Britain, you would know about The Archers. It’s a British radio soap opera which has been broadcast since the early 1950s and famously billed as “an everyday story of country folk”. Set in the fictional English village of Ambridge, it’s still going strong, with millions of people listening to each episode. With over 20,000 episodes broadcast to date, it’s the world’s longest-running radio drama. As a child, I wrongly assumed the programme had something to do with archery and having little interest in sports, bows or arrows, I never listened to it. The programme was introduced with a jaunty signature tune called Barwick Green, a maypole dance written in 1924 by the Yorkshire composer Arthur Wood. The comedian Billy Connolly once quipped that the theme was so typically British, it should be made the British national anthem.

This theme tune sprung to mind when I was listening to some English folk dances the other day. I began to wonder how we would define “folk dances” or “folk music”. In the end, I couldn’t think of a convincing definition so instead went to the kitchen for a gin and tonic, for by then the sun was well over the yardarm. The expression “folk music” is a relatively new one and originated sometime during the 19th century though often applied to music from much earlier. Searching for a definition, I turned once again to my weighty tome entitled The Oxford Companion to Music which devotes two pages to the subject. (Ironically, the same book devotes four pages to Beethoven.)

Traditional folk music has been defined as “music transmitted orally”, “music with unknown composers”, or “music performed by custom over a long period of time”. Clearly, they are not particularly good definitions. However, a consistent definition of folk music proves elusive and there’s still no certain one. It’s an extension of the term folklore, which was coined in 1846 by the English antiquarian William Thoms to describe “the traditions, customs, and superstitions of the uncultured classes.” To dig a little deeper, the word “folk” comes from the German volk which refers to “the people as a whole.”

Of course, throughout most of human history, music has been made by ordinary people during their work and leisure. Manual labour often included singing because it reduced the boredom of repetitive tasks; it kept the rhythm during synchronized pushes and pulls and it set the pace of many rural activities such as planting, weeding, reaping, threshing, weaving and milling.

The late nineteenth century saw an increase of nationalism throughout Europe and folk music began to receive renewed interest among composers and musicologists. In Britain, an interest in folk music had developed as early as the 18th century but peaked during the late 19th century when enthusiasts began to collect and write down folk music that they heard in the countryside. Many British composers, as indeed did many European and American composers consciously incorporated folk music into their work. The 20th century saw the emergence of a sub-culture of folk clubs and folk festivals.

The American folk music revival began during the 1940s and peaked in popularity in the 1960s though its roots extended much further back in time. The revival pushed folk music into popular culture and was led by people like Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan. In the 1960s a sanitized style of American folk music emerged, performed by groups such as Peter, Paul and Mary; described by one writer as resembling “two rabbis and a hooker”.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): Folk Song Suite. United States Marine Band cond. Maj. Ryan J. Nowlin. (Duration: 11.44; Video: 1080p)

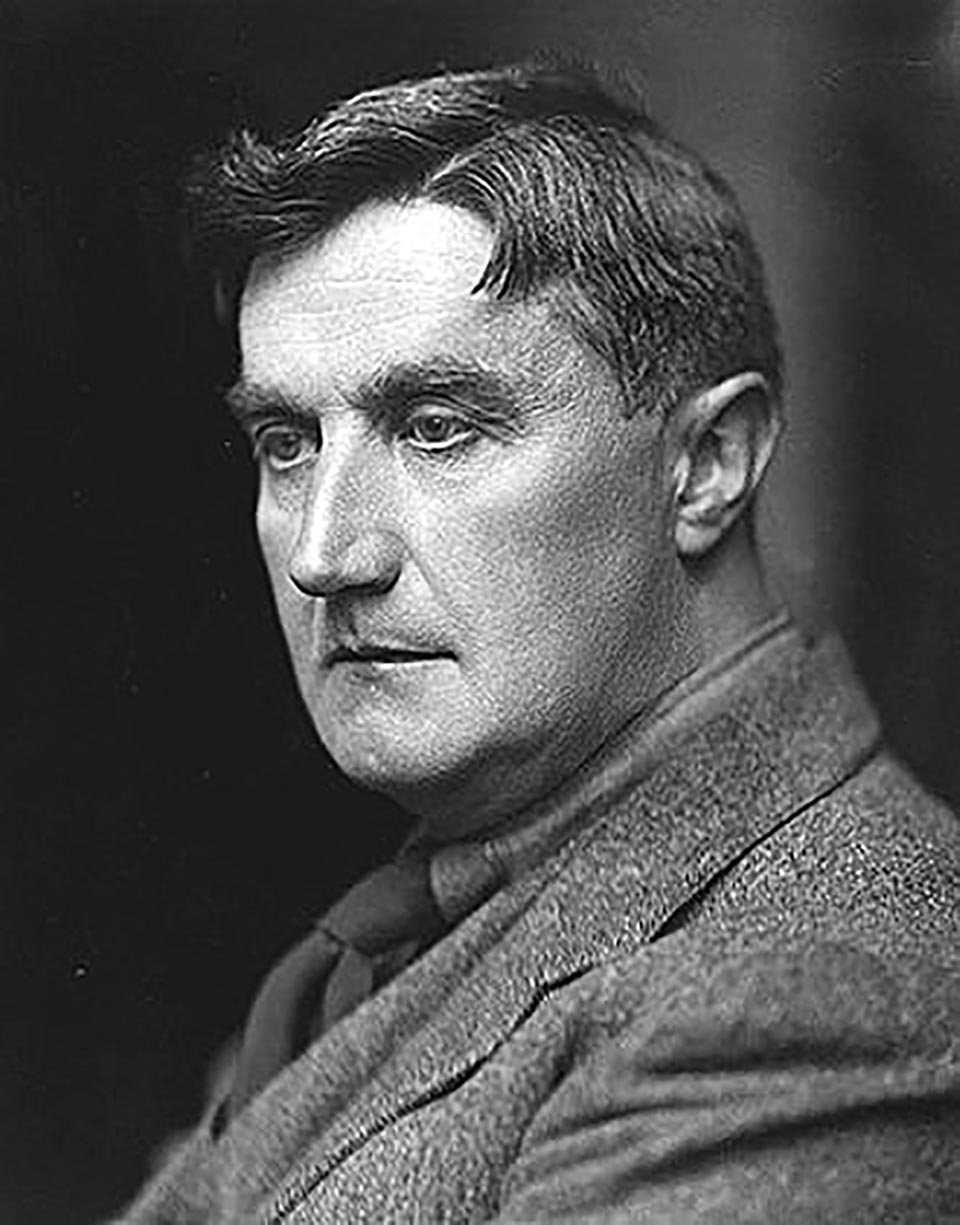

Vaughan Williams was a remarkably prolific composer whose works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies. His first name is pronounced as “Rafe” and he was strongly influenced by Tudor music and especially by English folk-song. In many ways was the quintessential English composer and his easily recognizable musical style broke free from the older German-dominated style of the 19th century.

Although he was born into a well-to-do family with strong moral views, he always sought to be of service to his fellow citizens and believed in making music available to everybody. As a result, he wrote many works for amateur and student performance. The Folk Song Suite is one of his most famous works. It was first published for military band and premiered at Kneller Hall in 1923. The piece was then arranged for full orchestra in 1924 by the composer’s student Gordon Jacob and published as English Folk Song Suite. The work uses the melodies of nine English folk songs, six of which were taken from the collection made by the composer’s friend and colleague Cecil Sharp, one of Britain’s most important collectors of folk songs.

The suite consists of three movements: a march, an intermezzo and another march. The first march is entitled Seventeen Come Sunday, the Intermezzo is subtitled My Bonny Boy and the final movement is Folk Songs from Somerset. The composer adds interest by combining the melodies in unexpected ways and adding characteristic, rich sumptuous harmonies of his own. This recording is the original version scored for military band. The performance by “The President’s Own” is wonderful; the solo playing, phrasing and sense of musicianship are superb. It’s a thrilling performance with perfect ensemble playing of military precision. Literally.