A couple of days ago I was in a local restaurant having coffee with a friend. Suddenly he put down his cappuccino and said, “I’ve got a good musical question for you.” I thought he was going to ask me something obscure like the name of Wagner’s dog. (And in case you’re wondering, Wagner’s first dog was called Robber, a massive 160-pound Newfoundland originally owned by the composer’s landlord. Wagner clearly admired large dogs as well as large operas.) But instead, my friend asked me to explain the difference between a symphony orchestra and a philharmonic orchestra. It’s a good question and judging by the number of online articles on the subject, it’s a question that many people ask.

Well, there are two answers, a short one and a long one. I will give you both. The short answer is “nothing”. The long answer will require seven hundred words, so take a deep breath. But if you can’t be bothered for all that reading, go and do something else. I couldn’t care less. Just don’t expect a Christmas card from me next year.

Perhaps it’s better to unpack the question bit by bit and first look the meaning of the word “orchestra”. Oddly enough, originally it wasn’t a thing but a place. My hefty but ever-reliable tome, The Oxford Companion to Music states that the word has its origins in ancient Greek theatre and the word orkhēstra (“dancing place”) was the area in front of the stage where the chorus danced and sang during performances.

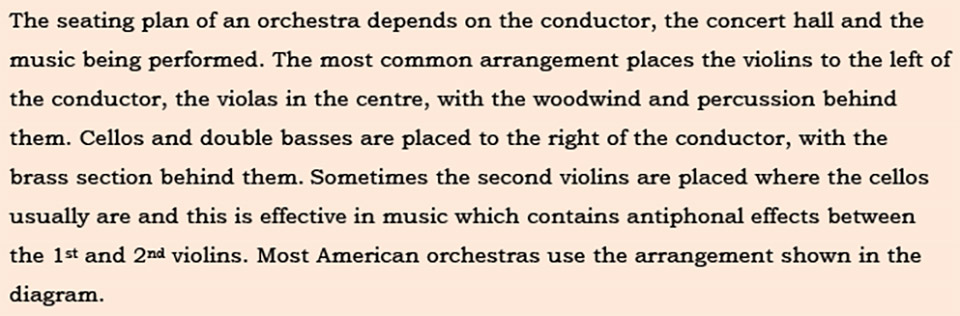

It was usually a flat circular or semi-circular area and the more up-market ones were paved with marble. In Roman theatres which often had a similar design, the orkhēstra was sometimes used for VIP guests such as senators or nobility. “The first Italian operas,” the article continues, “which appeared in the early 17th century were based on classical drama and it seemed logical to retain the term “orchestra” which gradually came to be used for the ensemble that played there.”

The ensemble that we would recognise as an orchestra didn’t really emerge until the middle of the eighteenth century. Before then, instrumental ensembles consisted of a motley collection of instruments and whatever happened to be available, but invariably with strings and a keyboard instrument.

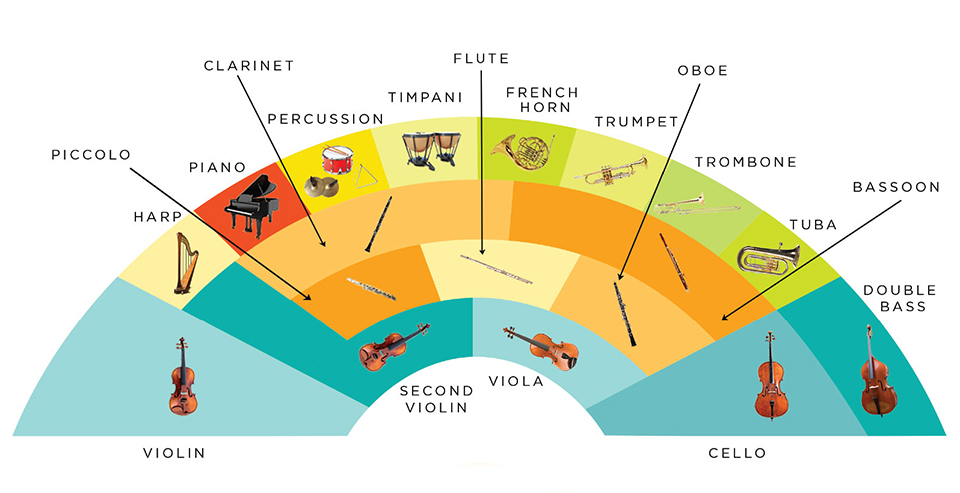

Early symphonies were usually scored for a small string section plus a few woodwind instruments and a couple of horns to add colour and contrast. Like the burgeoning cites of eighteenth-century Europe, the orchestra itself was growing to meet the musical demands of composers. By the time Tchaikovsky’s was adding the finishing touches to his Symphony No. 4 in 1878 orchestras were much the same size as they are today, with well-defined strings, woodwind, brass and percussion sections.

The word symphony comes from the ancient Greek symphōnía, meaning an agreement or concord of sound. During the Middle Ages, the Latin form symphonia was used to describe various musical instruments. During the Renaissance and Baroque eras, the word had changed to mean almost any music played by instruments rather than sung. It could also refer to instrumental interludes that were part of a larger dramatic work. For most of the Baroque era, the words symphony and sinfonia were used interchangeably for a range of different compositions, including instrumental pieces used in operas.

By the 18th century the opera sinfonia, had become pretty well standardized into a format of three contrasting movements: two fast movements separated by a slow one. This became the template for the 18th century symphony, but it became the custom to write four-movement symphonies with the addition of a minuet after the slow movement. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians states that “the symphony was cultivated with extraordinary intensity in the 18th century”. It played a role in many areas of public life, including church services, but there was amn enthusiasm for symphonies among the European aristocracy.

The expression “symphony orchestra” is therefore generic and it’s used for orchestras that are large enough to play symphonies. It implies a band of at least twenty players though in practice, often considerably more. Today of course, we can use the word for any large ensemble of players, such as a wind orchestra, a jazz orchestra or a Javanese gamelan orchestra.

But where does “philharmonic” come in? The word itself derives – in a rather roundabout way – from the Greek philos (“loving”) and harmonica (“harmony”). In 1813 when there were no permanent London orchestras, a group of London music professionals set up the Philharmonic Society of London. The Society’s aim was “to promote the performance, in the most perfect manner possible of the best and most approved instrumental music”. The Society commissioned Beethoven to write his Ninth Symphony and commissioned Mendelssohn to write his Italian Symphony. The Society also hired distinguished conductors including Ludwig Spohr, Hector Berlioz, Richard Wagner and Peter Tchaikovsky. The Society continues its work to the present day and is headquartered in a handsome building in Central London’s Great Marlborough Street. It became the Royal Philharmonic Society during its 100th concert season in 1912.

It was not the first of these philanthropic musical societies. The Philharmonic Society of New York was founded fourteen years earlier in 1799. In the following years, many other similar societies were founded, often with their own orchestras which usually included the word “philharmonic” in their name.

And there we have it. “Same-same, but a little bit different” as they might say in these parts. While the expression “symphony orchestra” is generic, a “philharmonic orchestra” is technically a symphony orchestra founded by a philharmonic society. At least, it was in the past. During the 20th century the word was used more freely and the words “symphony” and “philharmonic” are now virtually interchangeable. The London Philharmonic Orchestra was formed in 1932 and the name was chosen to distinguish it from the London Symphony Orchestra which had been inaugurated almost thirty years earlier.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791): Symphony No. 29 in A major K201. Ensemble Philmusica Tokyo cond. Christoph Koncz (Duration: 23:49; Video: 1080p HD)

Mozart completed this elegant symphony on 6th April 1774 after returning in the autumn of 1773 from a trip to Vienna with his father. It could be regarded as among the finest of all his early works. It was one of seven symphonies which Mozart composed for the new and grandly-named Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg Hieronymous von Colloredo. It has since become one of Mozart’s most popular works yet he was only seventeen when it was written. Oddly enough, no one is quite certain how many symphonies Mozart wrote. For many years, it was always assumed that he wrote forty-one, but recent research has shown that there were probably several others that have since been lost. This delightful and graceful work is scored for two oboes, two horns and strings. The Ensemble Philmusica Tokyo is virtually a chamber orchestra but typical in size of an 18th century orchestra which was made up mostly of strings plus a couple of woodwind or brass instruments. It’s perfect for Mozart because this is pretty much as he would have heard the symphony himself.

For a seventeen-year-old living in the late 18th century, this is a remarkable achievement. Mozart set the work in the four-movement format which was then fairly standard and in all the movement except the third one he uses a kind of musical template known as sonata form, a three-part structure which has two principal themes and develops them during the middle section. The first movement shows all the characteristics that were to define Mozart’s musical style, while the serene and pastoral second movement is scored for muted strings with limited use of the winds. During the 18th century, the third movement had become standardized as a minuet, and borrowed from the social dance, though the symphonic style of the minuet was more sophisticated or dramatic and usually included a middle section known as the trio. The energetic last movement fairly bowls along and shows the young Mozart as his most brilliant, full of invention, with confident youthful zest and sparkle.