“There is nothing wrong with your television set. Do not attempt to adjust the picture…We will control the horizontal. We will control the vertical…”

If you are over A Certain Age, these words may bring back memories of television of the 1960s. You might also recall messing about with the control knobs to prevent the image from inexplicably rolling, or turning into meaningless diagonal patterns, which it tended to do at moments of high drama. To anyone under forty, the references to the horizontal and the vertical are probably meaningless, because by the early 1980s improved technology had rendered these manual controls unnecessary.

The quotation comes from the spoken introduction to an iconic television series called The Outer Limits which first appeared in the early 1960s. Many composers have also pushed music to the outer limits, especially during the twentieth century. Even so, the quest for newness isn’t particularly new.

In the fifteenth century, the Flemish composers Johannes Ockeghem and Josquin des Prez were pushing musical techniques forward and in the sixteenth century, Adrian Willaert was developing chromatic harmony and creating new musical structures. But there were dozens of others. Frescobaldi in the seventeenth century wrote virtuosic passages that challenge performers today, and some of his music delved deeply into chromaticism. The beginning of the twentieth century saw some of the greatest changes ever in music composition. But what about the sixties, when The Outer Limits was scaring the wits out of its audience? What was new then?

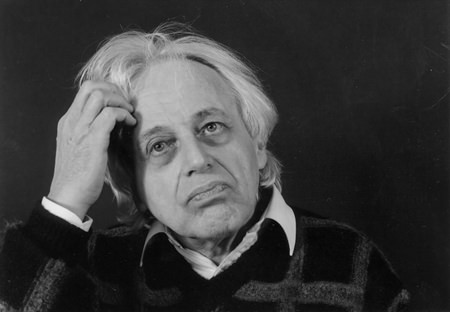

György Ligeti (jurj LIH-geh-tee) wrote this piece in 1967. It’s a powerful, brooding work in which he takes us by the hand (or, more precisely by the ear) and leads us into an alien, uncharted territory where reality and unreality are indistinguishable. Don’t try to search for “meaning” in this music: it doesn’t actually describe anything in the sense that Smetana’s Vltava describes a river, or Debussy’s La Mer evokes images of a troubled sea.

Lontano begins almost inaudibly with a single A flat on the flute, then gradually other instruments enter playing the same note. They’re joined almost imperceptibly by the trumpets but then the woodwinds move one by one down to G, thereby creating an increasingly cutting dissonance. If you’ve not heard this piece before, your first reaction could be, “What’s going on here?”

Ligeti wrote an explanation (but take a deep breath). “The harmonic crystallization within the area of sonority leads to an intervallic-harmonic thought process… achieved with the aid of polyphonic methods: the fictive harmonies emerge from the complex vocal woven texture and the gradual opacity and new crystallization are the result of discrete alterations in the individual parts”. Yes, well. Perhaps it makes more sense in the original Hungarian. He seems to be saying that many horizontal threads of simultaneous melody sometimes combine to produce brief moments of recogniseable harmony.

From time to time, a familiar-sounding chord emerges through the rich texture then fades away as quickly as it appeared, tantalizingly out of reach. I have always loved Lontano and find it immensely satisfying. The score contains many detailed written instructions and interestingly, the piece ends with a silent bar which lasts between ten and twenty seconds. Not many people know that.

The title of this amazing work is derived from the Greek word poly meaning “many” and morph meaning “shape” or “form”. Another Greek word – aukso (“growth”) was borrowed by the orchestra, which is one of Europe’s most progressive ensembles.

Krzysztof Penderecki (KZHISH-toff pen-der-ETS-kee) has been described as Poland’s greatest living composer, probably best known for his Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima and the St. Luke Passion. Polymorphia is scored for 48 stringed instruments and is probably one of the most scary-sounding works ever written. It was used in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining and perhaps more famously in William Friedkin’s The Exorcist.

The piece was first performed in 1961, thus pre-dating The Outer Limits by a couple of years. Conventional melody and harmony don’t exist in this sound-world that Penderecki created. He sometimes employed unusual playing techniques for which he devised his own form of notation.

Parts of the work are based on sound interpretations of electroencephalograms, which detect electrical activity in the brain and record it in the form of wavy lines. These were recorded at the Kraków Medical Center while volunteer patients listened to Penderecki’s own piece, Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, thus creating a pleasing symmetry which must have brought considerable satisfaction to the composer. Of course, you’d never have guessed that the music was inspired by brain waves, but it doesn’t really matter. It’s the thought that counts.

|

|

|