As you probably remember, most of Chile lies sandwiched between the Andes Mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is about 3,000 miles from the northern border with Peru down to the southern tip of the country and the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego. For centuries, Chile was accessible only by sea. The southernmost headland is Cape Horn, first rounded in 1616 by Dutch navigators and named after the city of Hoorn in the Netherlands. More significantly for mariners, Cape Horn is where the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet. About a hundred years earlier in 1520, the first European set foot on this land. The foot belonged to the Spanish explorer Ferdinand Magellan and the sea passage that separates Tierra del Fuego from the mainland is named after him. There are many theories about how Chile got its name. The explanation I find most alluring is that it comes from a Mapuche word which means “where the land ends”.

You might be surprised to know that they’ve been growing vines in Chile since the sixteenth century, after the country was colonized (or invaded, if you prefer) by the Spanish. The earliest Spanish conquistadors arrived from Peru in the north, hoping to exploit the area for gold and silver. But finding little of value, they traipsed back to Peru. Later, other groups of Spanish conquistadors and missionaries brought European vines – and religion – to the region. According to local legend, the first of these were planted by the conquistador Francisco de Aguirre himself. The vines may have originated from established Spanish vineyards in Peru where Francisco lived along with his retinue of soldiers and slaves.

It would have seemed rational if the Spanish newcomers encouraged the locals to develop their own wine industry. But not a bit of it. During Spanish rule, Chilean vineyards were severely restricted in production and the Chileans were instructed to buy all their wine from Spain. Most of them didn’t, because they preferred their own wine, though it may have been little more than rustic plonk. In any case, after a long voyage across the Atlantic, any Spanish wine would probably have become oxidized and barely drinkable. In 1641, in the true spirit of imperial colonialism, the mean-minded Spanish banned Chile from exporting its wine, but this ruling was also largely ignored.

During the mid-19th century, the Chilean wine-makers’ luck changed due to the disastrous arrival of the phylloxera vineyard epidemic in Europe. With countless French vineyards in ruins, many wine makers moved to South America bringing their experience and vinification techniques with them. As a result, the history of wine making in Chile has been largely influenced by the French, especially the wine-making traditions of Bordeaux. The burgeoning of European vineyards during the early twentieth century put Chilean wines temporarily in the shade and Chilean wine fell out of popularity abroad. But in later years, substantial foreign investment and technical advances had an enormous impact on the industry with the result that today Chile is producing some world-class wines.

Toby Morrhall has been a wine buyer for The Wine Society since 1992, having previously been a buyer for Sainsbury’s. He wrote recently, “Chile first became known for its cheap Cabernets and Merlots made from high yielding vines in the fertile Central Valley. However, Chile is no longer a cheap country. Its economy is based on copper and it’s the world’s largest producer. Labour for the wine industry is becoming more expensive and scarcer…and energy costs have risen rapidly. The future for Chile is bright, but it’s not for cheap wines. Chile has incredible potential for quality and is only just scratching the surface. This remarkable country includes all the world’s climates apart from sub-tropical and tropical. Different grape varieties need different climates to prosper and Chile can accommodate all of them.”

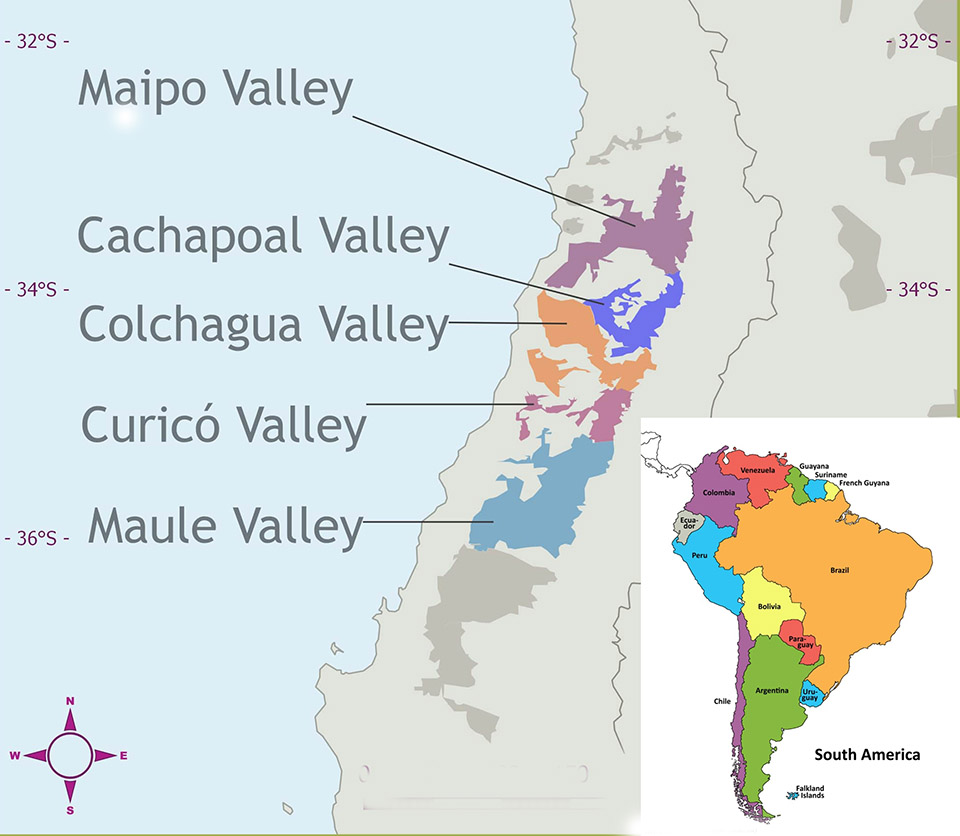

By the turn of the 21st century. Chile’s export increased, becoming the third largest exporter to the United States. Most of Chile’s vineyards lie along an 800-mile central stretch of land that has a temperate climate like that of California. Viñedos Errázuriz Ovalle is a large family-owned wine estate in Chile, with over 2,500 hectares of vineyards in the premium Colchagua and Curicó valleys. Since the mid-1990s, the family have transformed the estate, producing outstanding quality grapes. The diversity of terroirs across this vast estate allows the wine-making team to produce an exceptional range of every-day drinking wines which display great freshness and purity of flavour. The grapes are grown on the large Viñedos Marchigüe (bee-NYEH-dohs mar-TZEE-way) estate which was founded in 1994 in the town of the same name, located near the coastal area of the Colchagua Valley. The company handles a range of local wine brands including those of Viñedos Errázuriz Ovalle.

Panul Reserva Sauvignon Blanc 2022, Viña Marchigüe (Chile) ฿699 @ Villa Market

The Panul range of wines includes a selection of fourteen popular varietals. This vegan Sauvignon Blanc comes from grapes grown in the Curicó Valley. To my surprise, this bottle was closed with a cork. Nearly all everyday wines these days are instead sealed with the so-called Stelvin closure, a type of aluminum screw cap. This particular cork turned out to be a real pig, and I had to ferret out my strongest twin-lever bottle opener to haul it out. It’s useful to have one of these devices, because they can deal with the most stubborn corks when a simple T-shaped cork-screw simply wouldn’t stand a chance. “But why?” I kept asking myself, because a screw-cap is just so much more convenient for everyday table wine. Chilean tradition, I suppose.

Sauvignon Blanc (SOH-vihn-yohn BLAHN) is a green-skinned grape variety that originates from France. The name comes from the French words sauvage (“wild”) and blanc (“white”) and probably refers to its “wild” origin as an indigenous grape from the South West of France. It’s planted in many of the world’s wine regions. The makers describe this wine as having “a zesty, herbaceous and extremely refreshing style” a description with which I would entirely agree. The grape harvest was in late February and early March 2022, when the grapes had reached their maximum expression. The grape must was then fermented in stainless steel tanks for a couple of weeks at 13-14º C, thus preserving the natural freshness of the wine.

It has a distinctive greenish tinge, typical of Sauvignon Blanc but what struck me most was the lovely delicate aroma that immediately drifts out of the opened bottle. Assuming, of course that you succeed in pulling out the cork. It’s a fresh, delightfully scented aroma of white peach, fresh tangerine and herbs.

On the palate the texture is soft and smooth but there’s a precise acidic grip which follows right through to the surprisingly long finish. I especially appreciated the balance, because the fruit has been kept in restraint and not allowed to dominate the taste. At just 12.5º ABV, this is a lively, light-bodied wine; completely dry and with a zesty acidity. Even so, the acidity is much less assertive than some of the toe-curling Sauvignon Blancs from New Zealand.

Served well chilled, this pleasant wine would make an excellent accompaniment for light fish or chicken dishes. The wine is light, so keep the pairings light and try it with turkey, pork or smoked salmon. Some people associate red wine with cheese, but many whites make even more successful partners. This Sauvignon Blanc proved an excellent partner for some splendid French Coulommiers cheese which I’d bought locally. Not often seen in these parts, it’s a gentle, soft-ripened cheese from the commune of the same name in northern France’s Seine-et-Marne. It’s rather like Brie in taste though smaller and thicker with a nuttier flavour. It goes superbly with Sauvignon Blanc. I’d like to try this wine with Chicken Kiev too, because there would be an attractive contrast between the buttery, herby filling and the vibrant acidity of the wine. I might try that tonight, if the dogs haven’t finished off the bottle.