France’s reputation as a leader in fine wine has been achieved because their winemakers have spent many centuries learning the complex skills of wine-making. But not only that; they have studied the cultivation of grapes and paid close attention to the subtle differences in the various plots of land, the composition and drainage of the soils, the sun direction, the ambient temperatures and the influence of the local climate. The French have a word for all these factors. They refer to them as terroir, an all-encompassing word that influences the qualities of the grapes grown in a particular vineyard or even part of a vineyard.

When we think of the major wine regions of France, Bordeaux and Burgundy usually first spring to mind. But France has many more wine regions: between nine and eleven, depending on the way they’re counted. The Loire Valley is one of them, and it lies roughly midway between Paris and Bordeaux. It takes its name of course from France’s longest river, the Loire (LWAH) which rises in the Massif Central in the hills of the Cévennes. This region was featured by the Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer Robert Louis Stevenson who, in the late 1870s, trekked the Cévennes with his truculent and stubborn donkey named Modestine.

From the Massif Central, the river flows north through Pouilly-sur-Loire to Orléans and then west through Tours and Nantes until it reaches the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. On its journey to the sea, the river passes through the great Sauvignon Blanc regions of Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé and through the Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc heartlands of Anjou, Vouvray and Saumur before finally reaching the most westerly wine region of Muscadet.

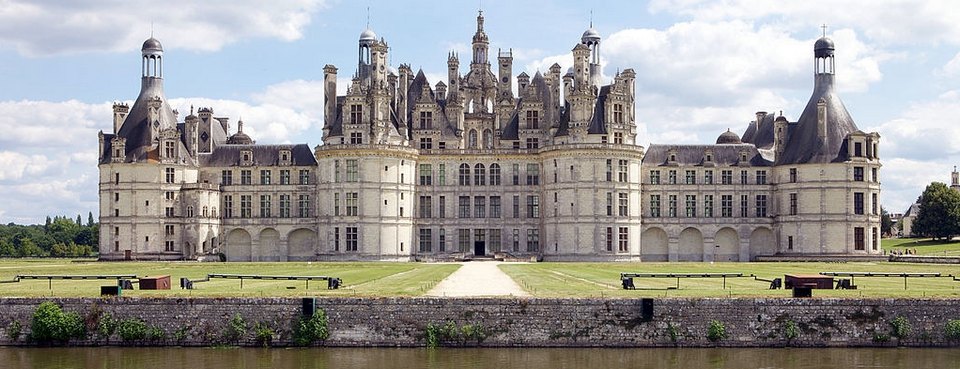

The Loire Valley has been called the “Garden of France” because of the many vineyards, orchards and cherry fields which line the banks of the river. The Loire Valley is also home to three hundred castles, which range from grim-looking feudal strongholds of the 10th century to ostentatious palatial residences built five hundred years later. When the French royal families began building their magnificent castles in the Loire Valley during the sixteenth century, the aristocratic classes, not wanting to be too far from the seat of power, followed the trend.

Winemaking in the Loire Valley dates back 2,000 years to when Romans planted the first vineyards. Over the years, the vineyards expanded dramatically and by the High Middle Ages, they were mostly in the hands of Augustine and Benedictine monks. At the time, Loire Valley wines were the most esteemed wines of France, even more prized than those from Bordeaux. Today, The Loire is the third-largest appellation in France and produces enormous quantities of everyday table wines – around 400,000,000 liters each year. The region also produces a smaller quantity of top-quality premium wines.

Production of the pink wine known as rosé has expanded significantly in the Loire Valley in recent years. It has become France’s second-largest rosé wine-producing region and most famous perhaps for the fruity Rosé d’Anjou with its characteristic aromas of raspberry and redcurrant. People sometimes assume that rosé (ro-ZAY) is a relatively modern invention, but its origins can be traced back to medieval times. It was probably first made in or near Marseille, that sprawling cosmopolitan city on the shores of the Mediterranean. For years, rosé was dismissed by wine connoisseurs as undistinguished plonk, but those days have long since gone and in more recent times, many wine makers have taken the style more seriously and some produce top-quality rosé wines.

Many rosés are not pink at all, but range from pale orange to a faint purple, depending on the grapes used and the way the wine was made. Fresh grape juice is almost colourless when it’s pressed and the colour comes mostly from the grape skins. When red wine is made, the skins (usually along with the seeds and stems) are left to soak in the grape juice for anything between three and a hundred days. The process is known as maceration and it draws the colour out of the skins into the grape juice. Rosé, on the other hand requires maceration of just a few hours to create the delicate pink colour for which it is so admired.

A glass of ice-cold rosé looks tantalizingly tempting and perfect for light meals, al fresco or otherwise. Rosé is nearly always dry or off-dry and best served really cold. Rosé is not intended for ageing, so it’s usually better to drink it young. It makes an excellent apéritif but also goes well with a surprisingly wide range of foods. In fact, you can drink rosé with almost anything.

J. de Villebois Pinot Noir Rosé 2022, Val de Loire (France) Bt 739 @ Villa Market.

Rosé is the ideal choice for light snacks on warm summer evenings. This one is designated IGP Val de Loire and as you might recall, IGP stands for Indication Géographique Protégée. In practical terms, this is a guarantee of quality and a notch above the basic Vin de France appellation. The wine comes from the family winery of J. de Villebois in the Loire Valley. Descended from a 19th century French family resident in the Netherlands, Joost and Miguela de Villebois are Sauvignon Blanc specialists but they also grow some Pinot Noir, the classical red grape of Burgundy. Their website explains how they attempt to “translate” the terroir of each vineyard and each grape variety into wines that best show what nature offers the winemaker.

This rosé is made solely from Pinot Noir (PEE-noh NWAH) grapes grown in selected terroirs, harvested at night to benefit from the low temperature. The wine is a lovely light orange-peach colour and looks really inviting in the glass. And this, incidentally is why wine glasses should always be transparent rather than coloured. The aroma brings floral, fruity aromas of cherry and raspberry and a suggestion of pomegranate. The mouth-feel is fresh, remarkably smooth and silky, with rounded light fruit and minimal acidity. Although the wine is unmistakably dry, there’s a hint of sweetness and the long and dry satisfying finish brings a delightful touch of tartness, a bit like sour cherries. At just 12% ABV this is a light and charming wine made in an interesting and novel style.

The grapes were evidently harvested early while still fresh, and gently squeezed in a pneumatic press to obtain this delicately coloured wine. The grape juice was fermented in stainless steel tanks for about twenty days and the wine bottled during the winter to preserve the aromas. The wine is fascinating just to enjoy on its own, and it would make an excellent apéritif. The makers suggest a serving temperature of 10-12° but you can drink it straight out of the fridge, because in this climate the wine will soon become warmer. If you prefer your wine with food, try something light such as a delicate chicken or fish dish. Even a simple Mediterranean-style salad would make a good partner as would spicy food or soft cheeses. If you enjoy rosé wines, you might like to give this interesting example a try.