Dividing lines are always controversial, but the 1960 movie Psycho is surely one of the clearest. It has some novel features: the first time, for example, that a flushing toilet was ever shown in a mainstream movie. It symbolized both the end of the “film noir” tradition of stylish crime-drama black and white movies with dark shadows and the beginning of something far more cynical in the form of slasher films. Psycho bridges the gap.

No other Hitchcock film had a greater impact. The ads shouted, “Do not reveal the surprises!” and cinemas would not let you in once the film had started. And it is true that no audience member could have predicted the surprises. They included the shock that Janet Leigh, the principal actress, was murdered a third of the way through or that her theft of US$40,000 actually has nothing to do with the overriding story line. The irrelevancy of the cash is known as a McGuffin, or red herring, and there are several others in the history of Hitchcock movies.

The key to the success of the movie is the relationship, however brief, between victim Janet Leigh and her murderer Anthony Perkins at the fateful motel. Hitchcock loved to describe the guilt of an ordinary person trapped in a criminal situation. It is true Marion Crane (Leigh’s character) does steal the enormous sum (in 1960) from her employer, but that’s just to help her lover continue his alimony payments and maybe marry her. Within 24 hours she determines to go back and repay the cash, but by then it’s too late.

Birds have a key role to play in this movie

Several of Hitchcock’s personal phobias are represented in Psycho, including a dislike of policemen. A highway patrolman wakes Marion from a roadside nap and almost sees the envelope with the stolen money. She trades in her car at the next town, but at the dealership is startled to see the same cop, arms folded, standing at his squad car and staring at her from across the street. The dealer is also suspicious of his new customer’s desire to seal the deal immediately and drive away. “It’s not that I don’t trust you but …” It’s the only time, he says, when a customer tried to high pressure the salesman.

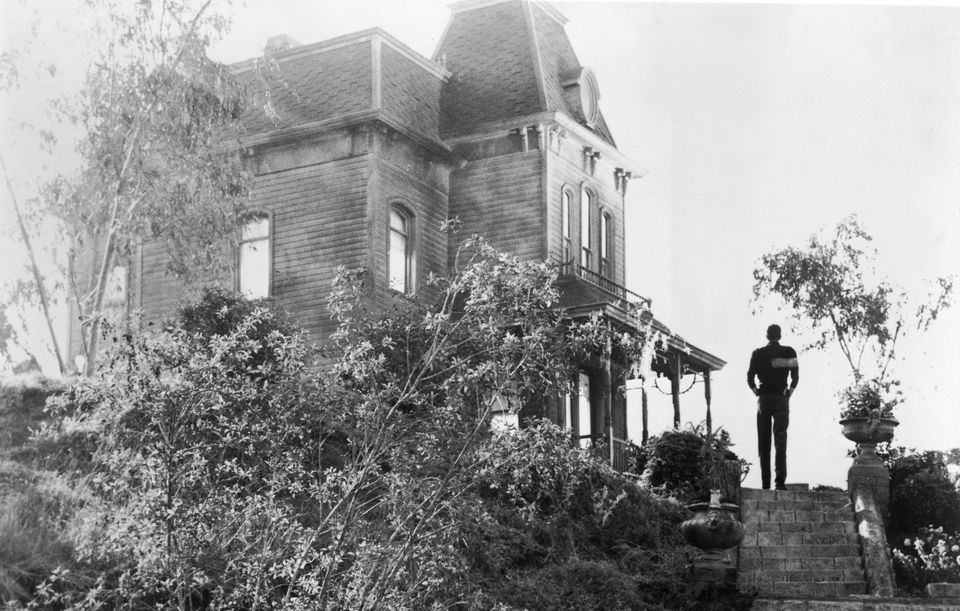

At length she pulls in to the failing Bates Motel and begins her short relationship with Norman Bates. The couple have a long conversation in the office parlor where there are many indications Norman is a bird of prey stalking the innocent. She signs in with the surname Crane, the office has many stuffed birds (ready to swoop down) and Norman himself munches candy in a bird-like fashion. But Marion has heard the angry voice of Norman’s mother and sympathizes with his plight even suggesting she be put in a care home. Norman is both touched and threatened by Marion’s interest. That is why she must die.

Then there is the shower scene, perhaps the most famous thirty seconds in movie history. Unlike modern horror films, Psycho never really shows knife striking flesh. There are no wounds shown. There is blood but not much of it. Hitchcock confirmed later it was chocolate sauce. The slashing chords of Bernard Herrmann’s soundtrack substitute for more grisly side effects and the slicing noises were actually donated courtesy of a melon. The whole episode remains the most effective slashing in movie history, demonstrating that situation and artistry are more important than graphic details.

Psycho’s only weakness is the final scene

The death of Marion is accompanied by the mopping up operation by Norman. Audiences still assume mother is the murderess and many members, if not most, are already siding with Norman and hoping he gets rid of all traces of the slaying. This was much to the credit of Perkins who successfully portrayed a madman whilst also demonstrating his likeability by skipping onto the porch, grinning and jamming his hands into his jeans pocket. There was no sign yet that the nice boy next door could be an assassin. We are encouraged to side with Norman, even wishing with him that the swamp will totally cover the car hiding Marion’s body. Not to mention the US$40,000 too.

The rest of the movie is melodrama. Marion’s sister turns up with the boyfriend Sam Loomis to search for the victim, whilst private eye Arbogast (Martin Balsam) is murdered in a shot that uses back-projection seeming to follow him down the stairs as he totters. And, of course, the identity of mother is eventually shown – a skeletal corpse. In order to fool us, no fewer than three actresses with different voices and body sizes played the part of mother. You were meant to be confused.

There is one surviving mystery of Psycho which is why Hitchcock included a finale sequence in which a long-winded psychiatrist lectures the assembled locals on the causes of Norman’s psychopathic behavior and actions. This is an anti-climax taken to the point of parody. Nobody, least of all Hitchcock, has been able successfully to explain this segment of the movie. Perhaps it was to satisfy the censors in the USA. None the less Psycho comments directly on all our fears: we might impulsively commit a crime, be questioned by the police, become the victim of a madman and, of course, worry that we might disappoint our mother. No film has ever achieved so much or shed so much light on our inner selves.

|

|

|