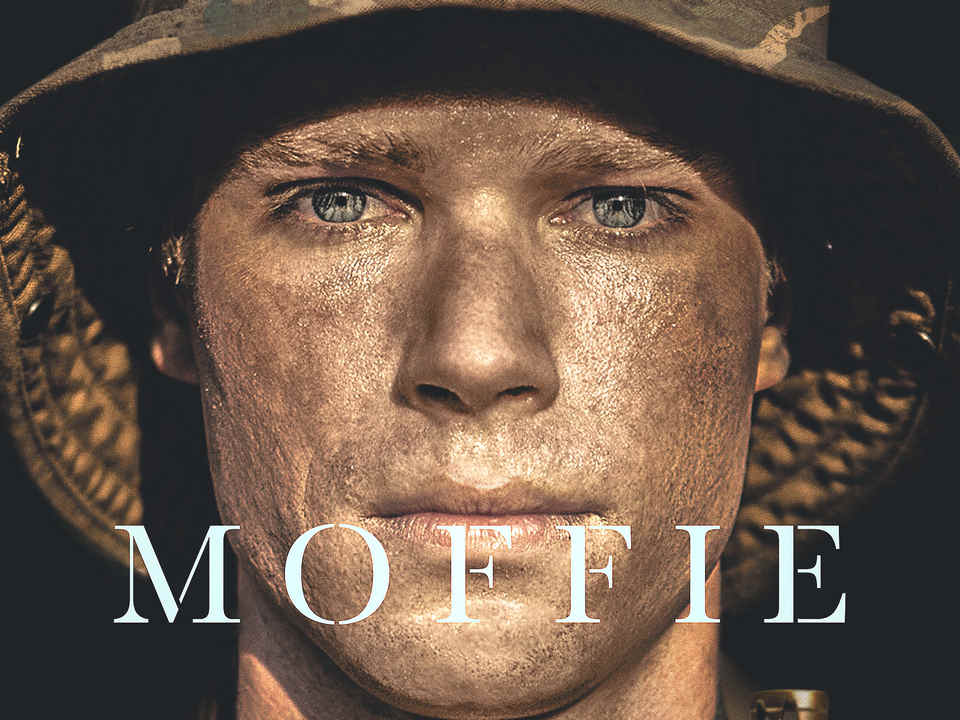

If Shepherds and Butchers (2016) described the rampant racism in South Africa’s system of capital punishment of blacks under Apartheid, Moffie (2021) examines extreme homophobia as well as white supremacy. A terrified teenager, played by Kai Luke Brummer, is conscripted into the discipline-crazy South African army in 1981 to fight the insurgents from neighboring Angola. He is a closeted gay.

Moffie, which means faggot or puffter in Afrikaans, is the second gay-themed drama of director Oliver Hermanus following his 2011 vivid Beauty which also exposed the violent homophobia universally present in the patriarchal white Afrikaans population. Moffie examines prejudice from the stifled perspective of an English-descended young soldier learning to adapt or die in his Afrikaan-run barracks. Whilst most films set in that period are all about the black-white divide, this movie is about rage in the ruling class.

Nicholas van der Swart, the teen actor’s name in the movie, is a placid and well-spoken youth who is devastated by his call-up papers. But he and his family put on a brave face, even throwing him a farewell party which is a kind of rite de passage into manhood. His father tries to ignore the fact that his son is destined to fight in a border war, spun by the South African government as a Christian campaign to prevent communism from spreading, and gives him a girlie magazine as a send-off present.

The training camp, preceded by an awful train journey, is horrendous in its brutality which is akin to that portrayed in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. More effeminate recruits are weeded out for special torture, but Nicholas gets by for the most part as he is tall, athletic and nimble. But when a silent and flickering understanding starts between him and rebellious squad member Stassen (played by Ryan de Villiers), Nicholas finds it hard to keep his head down. There is no sexual activity beyond gazing into each other’s eyes.

In fact, there is no hard sex in the movie. Two recruits are almost beaten to death when discovered together in a toilet, but the accusations don’t go beyond “kissing and stuff”. There is a flashback to Nicholas’ childhood when an innocent and unconscious glance in a public shower room unleashes an explosion of masculine insecurity and aggression by the furious attendant. The audience is invited to believe that Nicholas’ stoical attitude – he rarely smiles throughout the entire movie – has been born out of that experience as a child. He has learned to keep himself to himself in a hostile world.

Black persons appear only twice in Moffie. Early on, during the train journey carrying the recruits to the training camp, a black guy in a suit is waiting at a railway station and is covered in vomit by a bag thrown by one of the aggressive white teens. The victim scarcely reacts at all: he knows his place and the dangers if he answers in any way. At the end of the movie, Nicholas shoots a terrorist in battle and stands over the body with his usual expressionless gaze. It is perhaps the lack of visible emotion in this highly regulated and violent environment which is the hallmark of Moffie.

Meanwhile, of course, emotions of many kinds are brimming under the surface. Almost every scene in the movie is aesthetically considered and connected by theme as vast disgust, revulsion and silent yearnings lurk just out of sight. The movie is a queer coming-of-age movie totally without precedent in this genre. Moffie is a single word title which is derogatory in meaning. What intense meanings lie beneath it are the real issues in this unique movie.

|

|

|