I was thinking the other night (an unusual activity in itself) that many classical composers have been fascinated by birdsong. Olivier Messiaen and his musical bird catalogue spring to mind but we can go much further back in musical history. The oldest known composition using six-part voices is the thirteenth century English round Sumer Is Icumen In which includes cuckoo imitations. In 1735 Louis-Claude Daquin used cuckoo calls in a harpsichord piece entitled, not surprisingly Le Coucou though you need to listen carefully to hear them.

One of Handel’s organ concertos of 1738 became known as The Cuckoo and the Nightingale on account of the imitated birdsong in the solo part. Bird themes appear in Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute and Rossini’s The Thieving Magpie. Beethoven added several imitations of bird calls to his Pastoral Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s ballet Swan Lake has swans by the truck-load. Ravel composed a piano suite entitled Miroirs. One of the movements is called Sad Birds, which sounds as though it might be a musical depiction of Walking Street in the rainy season. One of Frederick Delius’s most well-known pieces is called On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring and includes a series of morose cuckoo calls played on the clarinet.

Messiaen referred to birds as “God’s own musicians” and he notated birdsong from all over the world and incorporated many of his transcriptions into his music. According to a poll conducted by Britain’s Classic FM, one of the most popular pieces in the UK is The Lark Ascending by Ralph Vaughan Williams, a composition inspired by one of George Meredith’s poems.

Respighi used a 78rpm recording of birdsong to add realism to his 1924 orchestral work Pines of Rome and almost fifty years later Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara used recordings of birdsong made near the Arctic Circle in his wonderfully evocative Cantus Arcticus. Then of course, from the legends of Russia comes Stravinsky’s wonderful music for The Firebird. I first heard this incredible work as a child a long time ago, when my father started collecting the newly-invented LP records.

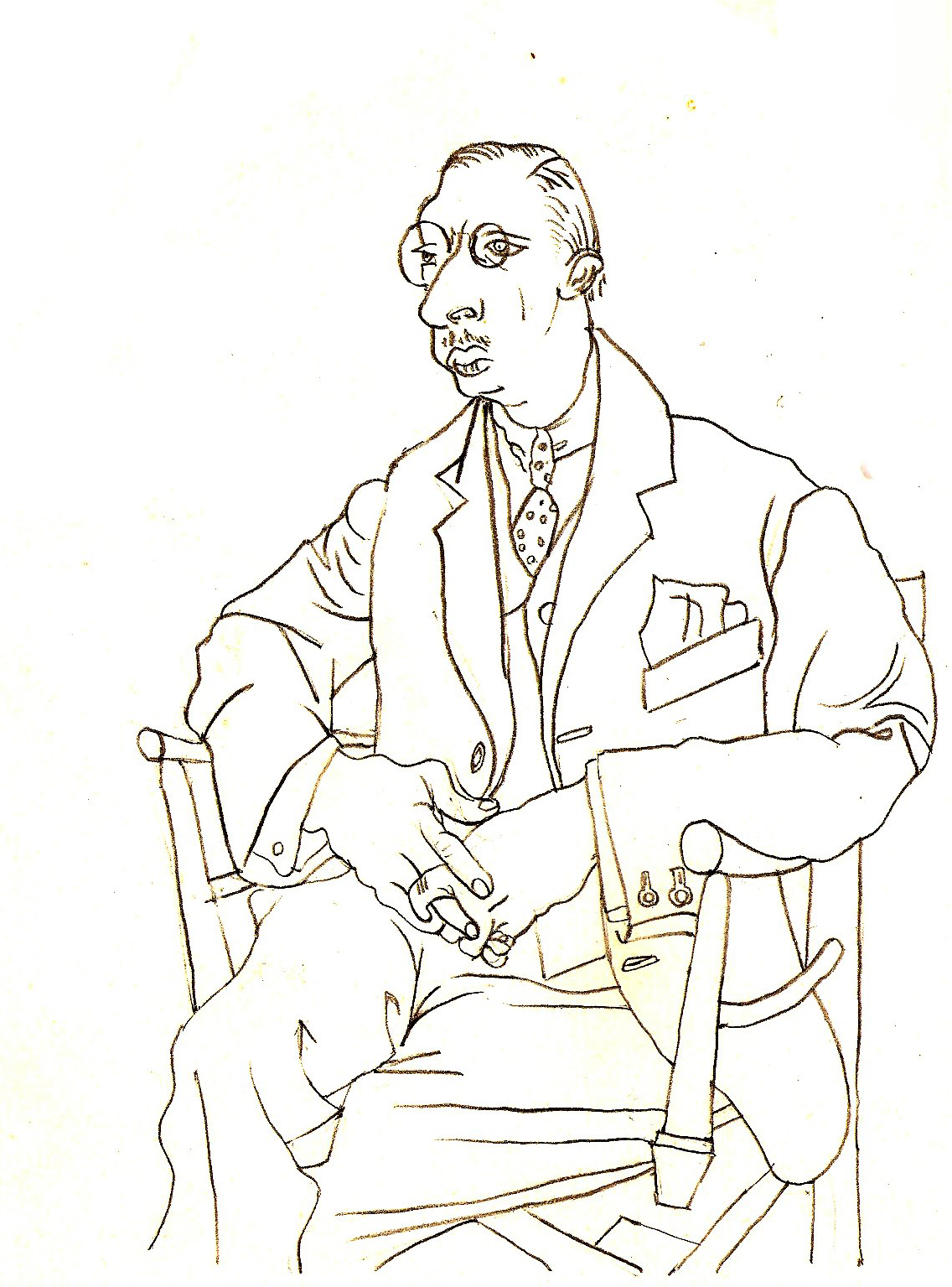

Igor Stravinsky was virtually unknown when Sergei Diaghilev hired him to compose for the Ballets Russes 1910 Paris Season. Diaghilev needed music for a ballet based on Russian folk tales about a legendary and magical glowing bird. At the time, Stravinsky was working on another ornithological project – his opera The Nightingale but put it aside for the commission.

The Firebird was scored for an enormous orchestra which included quadruple woodwind and three harps as well as a piano. The ballet was a momentous success and brought Stravinsky instant fame marking the beginning of a collaboration between Diaghilev and Stravinsky that produced two further ballets, Petrushka and The Rite of Spring which became iconic works of the early twentieth century.

Stravinsky created three separate suites from the ballet in 1911, 1919 and 1945 scored for a smaller orchestra than the original. The five-movement suite from 1919 is the most well-known. This is a superb performance with a French orchestra under a distinguished South Korean conductor who was once a student of bird-loving Messiaen. The rich, sumptuous score has countless magic moments. Just listen to the one at 18:19 where after a slow, hushed passage of tremolo strings, a solo horn announces the majestic melody that eventually brings the work to its heroic conclusion.

Eighteen years after The Firebird was premiered in Paris, Respighi wrote this delightful five-movement suite entitled Gli Uccelli (“The Birds”) scored for small orchestra. It’s based on bird-themed music by seventeenth and eighteenth century composers including Rameau and Pasquini.

Respighi was an expert in early music and among other academic ventures published new editions of the music of Monteverdi and Vivaldi. Music of the past also influenced his own compositions notably his three suites of Ancient Airs and Dances.

In The Birds, Respighi creates imitations of birdsong, fluttering wings, or scratching feet using the musical language of a bygone age, yet with touches that clearly belong to the twentieth century. The opening Prelude also appears at the end of the work and between1965 and 1977 was used as the signature tune for the BBC TV series Going for a Song. During the suite, we hear musical portraits of a pastoral dove, a scraping, clucking hen and a haunting movement inspired by the nightingale. In the sparkling finale, the music gives an animated picture of a playful cuckoo. All this might seem a bit simplistic but it’s sophisticated charming music, brilliantly orchestrated by a past master of the art.

|

|

|