Mention the words “night music” and I suppose the first classical piece that springs to mind is Mozart’s sprightly Serenade No. 13 in G Major, better known as Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. The literal translation is a bit misleading because the German word nachtmusik actually means “serenade”. Despite the title, it’s virtually a text-book example of an eighteenth century symphony.

Although it remains one of Mozart’s most popular works its origin is shrouded in mystery. Mozart completed it on August 10, 1787 and that’s about all we know about the work. Like most professional composers, Mozart nearly always wrote for commissions but we don’t know who commissioned it. We don’t even know why it was commissioned and the occasion for which it was intended. Oddly enough, no one seems to know where or when it was first performed. It’s possible that Mozart wrote it for one of the popular al fresco performances in one of Vienna’s parks or gardens. For some reason though, the work lay forgotten for years and wasn’t published until 1827, thirty six years after Mozart had breathed his last.

These days, we tend to hear the work played by string orchestra but it was actually written for a string quartet with optional double bass. There’s a fine video of this original version on YouTube, given by the Gewandhaus Quartet of Leipzig, which incidentally is the oldest string quartet in the world. It was established in 1808 and has been going ever since, though not of course with the original members.

You’d think there are dozens of classical works that are inspired by the notion of night time but I can’t think of many at the moment. But that’s hardly surprising at this stage of the week. There’s Mussorgsky’s Night on the Bare Mountain and Manual de Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain. Oh yes, then there’s the lovely Summer Night on the River by Frederick Delius. Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata doesn’t count, because the music has nothing to do with the moon or even night. The sonata acquired its romantic nickname five years after Beethoven’s death, thanks to an imaginative German music critic and poet named Ludwig Rellstab. Then there are the piano nocturnes by Chopin and by the Irish composer John Field, who is thought to be the inventor of the genre.

Mendelssohn was a brilliant child prodigy and the delightful string symphonies were written when he was twelve years old. He was seventeen when he wrote this overture in 1826 after reading August Schlegel’s German translation of Shakespeare’s play of the same name. The English musician George Grove (he of dictionary fame) called the overture “the greatest marvel of early maturity that the world has ever seen in music”. It was intended as a stand-alone concert overture and not until many years later did Mendelssohn write the incidental music for the same play. The famous Wedding March comes from this later work.

This is a charming, evocative work and remarkable for its striking orchestral effects, such as the imitation of scampering fairy feet near the beginning. It’s been suggested that Mendelssohn got the idea after hearing an evening breeze rustle the leaves in the garden of the family home.

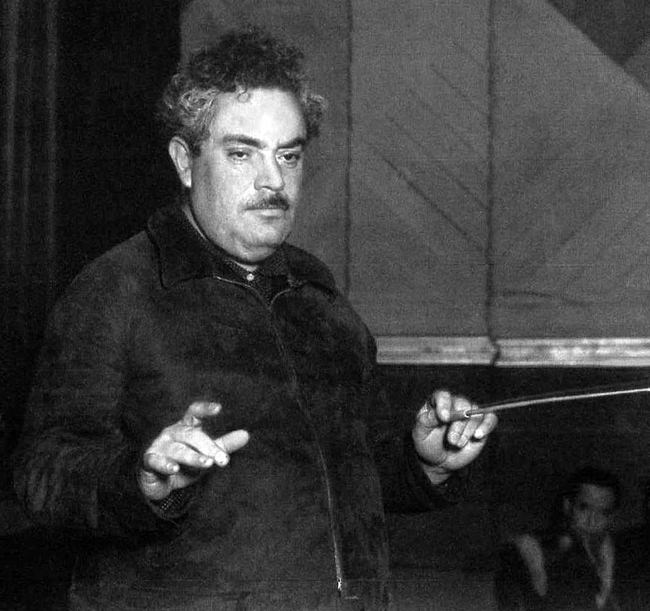

The conductor is the younger brother of the renowned Estonian conductor Paavo Järvi and this piece could hardly be more different from Mendelssohn’s gentle evocation of night-time. Revueltas is considered one of the most significant Mexican composers of twentieth-century. He used dissonance freely and his works have a rhythmic vitality and raw energy. His best-known composition is the score for the 1939 Mexican film La Noche de los Mayas (“The Night of the Mayas”).

Revueltas decided to create an orchestral suite from the dramatic music but he died before even starting it. The task was taken up by his younger compatriot José Ives Limantour and the reworking of the original film score preserves the composer’s native Mexican rhythms. The work is scored for a busload of percussion players and uses a selection of native Mexican instruments including the exotic-sounding caracol, huehuetl, sonajas, tumbadora and the tumkul. The work is symphonic in design and cast in four movements with this one, Night of Enchantment being the last.

You’ll need a good sound system or high quality headphones to fully appreciate this thrilling and relentlessly percussive music. Notice the so-called “Bartók pizzicato” near the beginning of the movement, when the string players pluck the string with such force that it slaps noisily against the fingerboard. Needless to say, the music is real blood-and-guts stuff and not for those of a delicate disposition.

|

|

|