Strangely enough, the word “orchestra” originally meant a place, not a thing. In ancient Greece, the orchestra was the circular space used by the chorus in front of the proscenium. It was not until the 17th century that the word assumed its modern meaning. The orchestra we know today has its roots in the groups of instrumental players who were employed by royal or noble families or those who could afford to employ resident musicians. Mind you, they weren’t paid very much but usually a good deal more that what churches offered, which was another source of employment for musicians.

Before 1750 the standardized orchestra was unknown. Ensembles at royal households were pretty small and consisted of whatever musicians were available, though stringed instruments predominated. Part of the reason was economics because the larger the ensemble, the more people you had to pay. In any case, musical performances were informal private affairs held in room a within a royal household. It wasn’t until the appearance of public concerts that larger orchestras became necessary.

In France, the first public concerts were called Concerts Spirituels because they were held on religious festival days when other forms of entertainment were closed. They flourished in Paris throughout the 18th century and the idea was taken up in other countries. Public concerts involved larger audiences and to meet the need for greater volume, orchestras began to expand in size. The string section remained the foundation while other instruments were added if and when they were needed. Most symphonies of the period for example, were scored for strings with just a couple of oboes and horns.

It was not until the early years of the 19th century that the full woodwind and brass sections began to appear. Part of the reason was that the development of music schools and colleges meant that more skilled instrumental players were available. By the end of the 19th century, orchestras sometimes consisted of sixty or seventy players. Some composers wanted even bigger orchestras to produce the sheer volume and expansive sounds that they needed.

Mahler scored his eighth symphony for a massive orchestra and choir, which is why it has acquired the nickname Symphony of a Thousand. And in case you’re wondering, the world’s largest orchestra was assembled in Australia in 2013 to achieve a new Guinness World Record. It consisted of seven thousand participants ranging from beginners to professional musicians. The gargantuan ensemble played a medley which included Waltzing Matilda and Ode to Joy. It’s all good fun but I don’t suppose you would want to hear it very often.

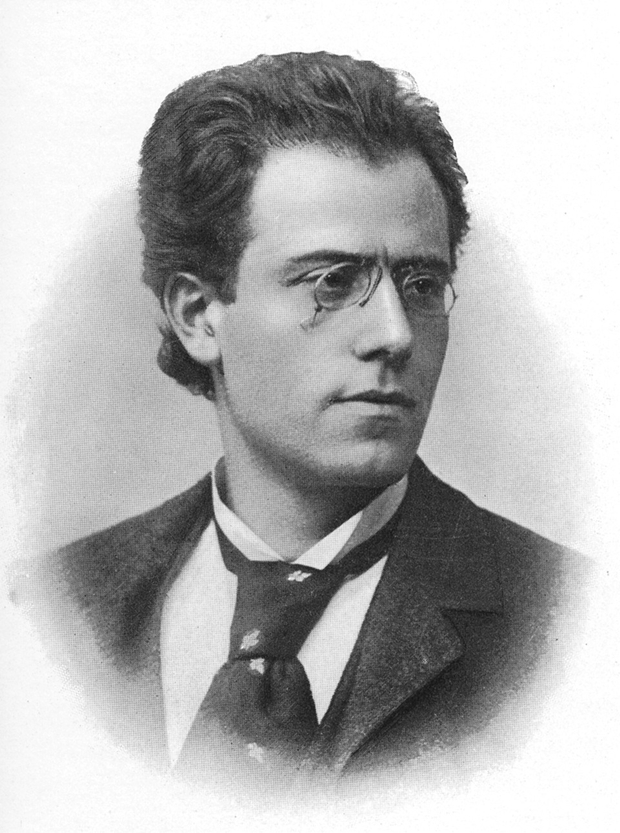

Well, can anything new be said about Mahler symphonies in a few words? I doubt it, but Mahler’s massive ten symphonies cover almost every aspect of human expression. They also form a cultural bridge between the German musical traditions of the nineteen century and those of the twentieth. After several decades of neglect, the 1950s saw Mahler’s work and especially his symphonies being rediscovered by a new generation of listeners. Mahler has become one of the most frequently performed and recorded of all composers. He completed this much-loved symphony in 1902. It’s a powerful, emotional work for a large orchestra and you’ll need to put an hour aside to hear it. If this seems a bit daunting, try taking it in smaller chunks – a movement at a time. I’m sure Mahler wouldn’t mind. The third movement (45:10) is best known from its use in the 1971 Visconti movie, Death in Venice.

The French composer Hector Berlioz was the son of a provincial doctor and attended medical school in Paris, before defying his family’s wishes and taking up music as a profession. His independent spirit and dismissal of tradition caused put him at odds with the conservative musical establishment of Paris. But presumably not the French government, which commissioned this Requiem, completed in 1837.

Berlioz scored his Grande Messe des Morts for over four hundred musicians: over 200 in the orchestra and another 200 choral singers. Berlioz evidently remarked that if there had been enough space, he would have preferred 800 hundred voices. It seems he was never satisfied. The orchestra includes four off-stage brass ensembles and sixteen timpani, though the performance in this video, recorded in Cologne’s impressive cathedral is somewhat scaled down. To my mind, the sound is more well-defined as a result. If you haven’t got an entire hour to spare, just listen to magnificent Tuba Mirum (“Hark the trumpet”) at 15:00 to get a sample of this fine work.

|

|

|