In London, carnival usually means only one thing: the Notting Hill Carnival, a lively three-day celebration with street parades around the residential and shopping area of the same name. Led by members of London’s West Indian community, it’s been going since the 1960s and it’s one of the biggest street carnivals anywhere. Even so, it’s not a carnival in the strict sense of the word.

The term carnival has probably come from the Latin expression carne vale, which means “farewell to meat”, signifying the supposed period of fasting and general restraint during the Christian season of Lent. Mind you, I can’t help feeling that a farewell to meat would be a jolly good thing for most people. Perhaps the world needs more vegetarians and vegans and I bet most pigs, sheep and cows would agree. Anyway, it would have been immensely satisfying to tell you that both composers of these two well-known concert overtures were vegetarians, but they weren’t. At least, not as far as I know.

By the end of the eighteenth century favourite opera overtures were being performed as separate items in the concert hall. During the early years of the nineteenth century, many composers started using the word for a stand-alone concert piece, probably because there were no other suitable terms available. They were nearly always fairly short, single-movement pieces for orchestra invariably with some kind of literary or descriptive associations.

Antonín Dvorák (1841-1904): Carnival Overture, Op 92. BBC Symphony Orchestra cond. Jirí Bìlohlávek (Duration: 09:51, Video: 720p HD)

I have to admit that this takes me back a good few years. I remember playing it when I was a cellist in a youth orchestra in Britain. There are some difficult moments in the cello part, and at the time I had a suspicion that old Dvorák had it in for us cellists.

The conductor on this recording also began his musical career as a cello player but eventually moved on to conducting. He worked with the Czech Philharmonic in the 1970s and later became chief conductor of the distinguished Prague Symphony Orchestra.

This work is one of three concert overtures that Dvorák wrote in the 1890s. He intended them to be played together, though in practice they rarely are. If you are new to Dvorák this is probably a good place to start. According to the composer, the lively opening section depicts a festival in full swing at which the noise of instruments is heard everywhere, mingled with shouts of joy of the people giving vent to their feelings in songs and dances.

There’s a lovely romantic and contemplative section in the middle of the overture and at 04:36 a wistful phrase appears on the cor anglais. Incidentally, this instrument is sometimes known by its old-fashioned and somewhat erroneous name the English horn, but it’s neither English nor a horn. At 05:20 the same phrase appears on the cellos and basses producing an ethereal and a magical effect. Then at 05:52 the carnival spirit returns and brings the overture to a joyful conclusion.

This lively overture was first performed in Paris in February 1844. Six years earlier Berlioz had completed his opera Benvenuto Cellini which had been inspired by the colourful memoirs of the eponymous sixteenth century Florentine sculptor. To create this stand-alone piece Berlioz used various melodies from the opera as well as some material from the opera’s carnival scene, hence the overture’s title.

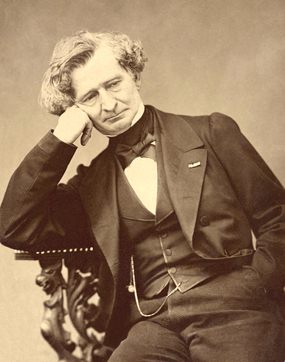

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Berlioz wasn’t a child prodigy and started studying music with the aid of text-books at around the age of twelve. His father was an eminent doctor and the first in Europe to experiment with acupuncture. After leaving high school in 1821, Berlioz was pushed off to Paris to study medicine. But medical studies didn’t interest him. In fact, he hated them. He enrolled instead for private music lessons and attended the Paris Conservatoire. Later, as an established composer, Berlioz acquired a penchant for huge musical forces and conducted several concerts with more than a thousand musicians. Considered by some as perhaps the greatest conductor of his era, he achieved further fame with his highly influential Treatise on Orchestration, published in 1844.

Berlioz was one of the most progressive composers of his time and astounded audiences with modern sounds, unexpected musical twists and original harmonies. Although this overture has a lively beginning, the first few minutes are dominated by a lyrical melody first heard on the cor anglais (yes, another one). Even if you don’t know the overture, you may well recognise this tune. Then at 03:40 the carnival really gets going and jollity abounds. There’s brilliant orchestration too, from a past master of the art.