I’ll leave you to complete the phrase but please try to think of something more imaginative than “chalk and cheese.” Anyway, the point is that I want to tell you about two interesting pieces which are about as different as they can get. In a way, they sit at opposite ends of a creative spectrum.

One of them is a pious and affectionate statement of love and religious devotion, while the other is an expression of loathing, terror and despair brought about by one of the cruelest leaders the world has encountered. The harmonic language is different too in that one of them gazes fondly back to the nineteenth century while the other sits firmly in the twentieth.

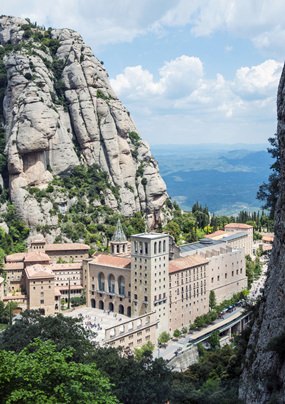

The Abbey of Santa Maria de Montserrat. (Photo/Chensiyuan)

The Abbey of Santa Maria de Montserrat. (Photo/Chensiyuan)

One work is written for a fairly small group of singers while the other is scored for an enormous orchestra. The only thing that the performances have in common is that they’re given by children or young adults who collectively have achieved world-wide recognition.

Antoni Pérez Moya (1884-1964): Virgo Veneranda. Escolania de Montserrat, cond. Llorenç Castelló (Duration: 7:34; Video: 720p HD)

In the year 1025, the Benedictine community of Santa Maria de Montserrat was founded near Barcelona in Catalonia. In case your Spanish geography is a bit hazy, Catalonia is that bit of Spain which sits up in the top north-east corner, next door to France.

Sometime during the early fourteenth century, the choir school L’Escolania de Montserrat was established. It is still in the same place today, right next to the Benedictine monastery nestling under the daunting crags of Montserrat’s Roca de St. Jaume. And just in case you’re wondering, escolania means “choir school” and Montserrat means “serrated mountain”.

The choir is made up of more than fifty boy sopranos and altos between the ages of nine and fourteen who come from various towns in Catalonia and other parts of Spain. The school provides full primary and secondary education with an emphasis on music. Each student is required to study an orchestral instrument plus the piano and of course participate in the choir which gives daily performances in the Basilica for groups of tourists from around the world. When the repertoire demands, the choir is augmented with lower voices, either ex-choirboys or monks from the abbey.

The midday singing of Salve Regina has become a popular tourist attraction as you’ll see from this video but despite the throngs of onlookers the magic remains. This performance uses only a couple of dozen singers but their characteristic choral sound and remarkable tone quality is sublime.

Virgo Veneranda (Virgin most Venerable) is a short choral work from the prolific but little-known Catalan composer Antoni Pérez Moya, remembered today for only a handful of works though he actually wrote over a thousand. This is a lovely piece with delicious twists of harmony that illuminate the soaring melodies and it’s accompanied on an impressive-looking four-manual modern organ.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975): Symphony No. 10. Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela cond. Gustavo Dudamel (Duration: 59:24; Video: 480p)

The performance of this magisterial symphony couldn’t be more different from the rarified atmosphere of the Basilica of Santa Maria. Dudamel conducts the work entirely from memory and at the start, you somehow get the feeling of embarking on a long journey.

The work dates from 1953 and was composed in the same year that Joseph Stalin died. Shostakovich wrote “I depict Stalin in my next symphony, the tenth. I wrote it right after Stalin’s death and no one has yet guessed what the symphony is about.”

The work begins in a dark reflective mood and ominous tensions begin to build during the first movement, which is actually an enormous slow waltz. In the second movement, you can almost sense the demonic evil and frenzied violence. It’s a short and fiery scherzo which the composer admitted was a musical portrait of Stalin who had the distinction of being described as “one of the most powerful and murderous dictators in history”. Dudamel takes the movement at a furious tempo and the orchestra plays brilliantly.

The third movement is a strangely troubled and macabre waltz that seems to be searching for something elusive while the final movement has some of the slowest music in the entire work and at times evokes a cold and barren wasteland. Later, it becomes more animated and optimistic and finally ends in a thrilling mood of triumphant defiance.

Dudamel is his usual exuberant self and brings out the best from these young Venezuelans, although it has to be admitted that some of them are not so young anymore. But even so, it’s a stunningly good performance and one of the most exciting that you’re likely to hear, if you can manage to ignore the inane chatter of the television presenters at the start.