It’s one of the most well-known split infinitives of the last few decades, thanks to the cult TV series Star Trek. Each programme began with a voice-over from Capt. Kirk (William Shatner) which included the line, “To boldly go where no man has gone before”. In later programmes the word “man” was replaced, presumably on the grounds of gender stereotyping, but the split infinitive joyously remained.

Of course, to be grammatically correct, it should be “to go boldly” but this doesn’t quite have the same gravitas. Anyway, the phrase came to mind when I was listening to one of the Bart๓k string quartets recently. He was one of the many composers who broke away from the conventional and took his music to where no one had gone before. As a schoolboy, I remember being thrilled on hearing a recording of his Divertimento for Strings. It sounded “modern” back then as did the string quartets, but somehow Bart๓k’s musical language seems to have mellowed over the years. Or perhaps we simply don’t get shocked by that kind of dissonance any more.

Like so many other composers, Béla Bartók (BAY-lah BAR-tohk) created his own musical soundscapes and you can often recognise his personal “Hungarian” sound within seconds. I suppose much the same could be said of people like Sibelius, Delius, Debussy, Stravinsky or Vaughan Williams. They developed the ability to build a musical sound-world that’s instantly recognizable. Many painters too had this same ability to create a unique visual style. Just think how easy it is to recognise a work by Caravaggio, Hieronymus Bosch, Max Ernst, Salvador Dali or Paul Cézanne. And you could probably recognise one of Mark Rothko’s enormous “Seagram” paintings at two hundred yards.

Béla Bartók (1881-1945): Concerto for Orchestra. The Orchestra of the University of Music Franz Liszt, Weimar cond. Nicolás Pasquet (Duration: 40:04, Video: 1080p HD)

Bartók left his home country of Hungary in 1940 and settled in America but within a short time he was diagnosed with leukemia. During his last years, he had a surge of creative energy and composed some of his finest works. One of them was the Concerto for Orchestra. Bartók completed the score in October 1943 and the work was performed two months later by the Boston Symphony conducted by Serge Koussevitzky who had commissioned the work. The title might seem rather odd because concertos are normally for a solo instrument with orchestral accompaniment. Bartók explained that he called the piece a concerto rather than a symphony because each section of instruments is treated in a solo-like manner.

It has become Bartók’s best-known orchestral work and if you are unfamiliar with this composer, this five movement concerto is a good place to start. It may have sounded “modern” seventy years ago, but now it falls easily on the ear with plenty of attractive Hungarian-style melodies and lively rhythms. The talented young students from the University at Weimar give a stunningly good performance too.

Elliott Carter (1908-2012): Concerto for Orchestra. Tanglewood Festival Orchestra cond. Oliver Knussen (Duration: 23:27, Video: 360p)

You may find Elliott Carter’s Concerto for Orchestra a bit of a challenge, even though he was one of the grand old men of American music. Like the Bartók work, Carter’s piece is a concerto in several senses, not only for the entire orchestra but also for soloists as well as small groups of instruments. It’s a four-movement work written in 1969 commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and it’s been praised by musicians and critics alike. Tom Service of The Guardian newspaper described it as “an incandescent blaze of musical poetry.”

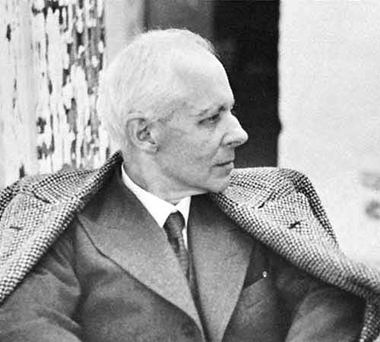

Even so, Elliott Carter wrote music of exceptional complexity and like Bartók, pushed music to where no one had gone before, boldly or otherwise. He was a remarkably prolific composer especially in his later years and published more than forty works between the ages of 90 and 100. After his 100th birthday, when most people would seriously consider taking a break, he wrote twenty more works.

Carter spent four years composing this concerto and it’s the most complex of all of his works. It’s possibly the most complex work written by anyone. The technical and musical challenges are such that at the premiere in 1969, some members of the New York Philharmonic considered the work almost unplayable, so this performance by these young Tanglewood musicians is all the more remarkable.

In the days before the concert, conductor Oliver Knussen evidently spent considerable time drilling the musicians at a series of intensive rehearsals. At the end of this incredible performance, there’s a standing ovation and a heart-warming appearance by the one-hundred-year old composer, accompanied by whoops and yells from a wildly enthusiastic audience.

|

|

|