It’s probably a pretty safe bet to state that the first music ever to be heard on this planet was made by the human voice. At some point in human evolution, perhaps even before recogniseable speech began to develop, people found that they could make sounds with their voices that were melodious – at least by their standards. The human voice can produce a wide range of sounds and as well as musical pitches, humans can also hum and whistle and make many percussive sounds using the throat or other parts of the body. With a few exceptions, singing is virtually the only human sound that has survived into European classical music.

Many centuries were to elapse before music became structured into modes or scales and these varied considerably from one culture to another. The nearest thing to a western choir emerged in ancient Greece around the second century BC when a chorus was needed for Greek drama.

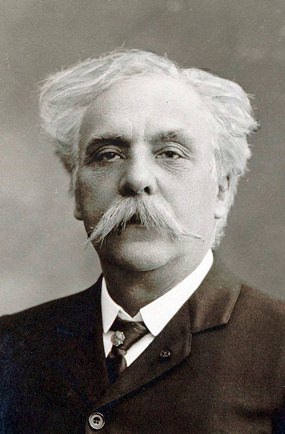

Gabriel Fauré in 1905. (Photo: Pierre Petit)

Gabriel Fauré in 1905. (Photo: Pierre Petit)

Choral singing in the form of simple chants was fostered in the Christian church and became standardised around 500 AD under Pope Gregory. The style of music that became known as Gregorian chant consisted of a single melodic line and many examples of these strangely beautiful melodies have come down to us today. Later, interest was added to these melodies by adding parallel vocal parts. The twelfth century French composers Léonin and Pérotin developed a choral style at Notre Dame in Paris known as organum in which the tenor part held the chant melody (from the Latin, tenere “to hold”) while the lower voices provided a sustained drone-like bass line.

It was another few hundred years that choral music with independent voice parts developed. During the Renaissance, roughly between 1400 and 1600, choral music was well-established and became sophisticated in its use of voices and harmonies. Although choral music originally developed in the church, secular choral music – especially madrigals – began to appear, thanks largely to the invention of printing. The Renaissance saw the divergence of choral music into two broad streams, one using liturgical texts and others using secular.

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924): Requiem, Op. 48. Sylvia Schwartz (sop), Roderick Williams (bar), Denmark Radio Concert Choir and Symphony Orchestra cond. Ivor Bolton (Duration: 38:16, Video: 1080p HD)

Gabriel Fauré composed this charming work in the late 1880s, revised it in the 1890s and finally completed it in 1900. Although it’s probably his best-known work, no one seems to know why he wrote it. The composer himself wrote in a letter to a friend that it “wasn’t written for anything – for pleasure, if I may call it that.” He scored the work for two soloists, chorus and orchestra and the vocal writing is interesting because while sometimes the choir sings in union, at other times he uses rich choral harmonies by dividing the tenor and bass sections.

The work is cast in seven movements and perhaps the best known are the lyrical Sanctus (at 14:04) and the Pie Jesu (at 17:21). The ethereal last movement (at 30:05), In paradisum is stunningly beautiful and quietly moving.

Carl Orff (1895-1982): Carmina Burana. Royal Chorale Cecilia Antwerp, Royal Gent Oratorio Society, Children’s Choir of Wilrijk Music Academy, La Passione Chamber Orchestra Eindhoven, cond. Paul Dinneweth. (Duration 01:03:44, Video: 1080p HD)

You’ notice that this work runs for over an hour, but with Songkran on its way you may need something to pass the time. Even if you have never heard the title before, you’ll surely recognise some of the movements, because they’ve been used in countless movies and television programmes.

Carmina Burana is based on twenty-four poems from the medieval collection of the same name. Compared to the chaste Latin liturgical text that Fauré used for his Requiem, this is more bucolic stuff which is often quite racy in nature. The poems cover a wide range of different subjects such as the fickleness of fortune and wealth, the ephemeral nature of life, the joy of the return of spring and the pleasures and perils of drinking, gluttony, gambling and sexual lust. Even so, don’t worry about children hearing it because all the words are in either Latin or Middle High German.

Orff really captured the spirit of the medieval period in his use of melody, infectious rhythms and simple harmonies. The choral writing is actually quite straightforward and declamatory and the music contains little development in the classical sense.

The cantata contains twenty-five separate movements and was written during 1935 and 1936. It became hugely popular in Germany after its premiere in Frankfurt in 1937 perhaps because of the perceived erotic tone of some of the poems. The composer himself thought it was the best piece he’d ever written and even told his publishers to destroy all his previous works, which of course, they didn’t.