Music has become so much a part of Christmas festivities that it’s difficult to imagine Christmas without it. Or at least, without Christmas carols. Although carols have become synonymous with Christmas and Advent, they can relate to any time of the year. The word comes from the Old French carole, a circle dance accompanied by singers which was popular during the middle ages.

Carols fell into decline in the sixteenth century but were revived during the nineteenth. Most of the well-known hymns and carols sung today were composed during that period. Several composers have used carols as a basis for choral or orchestral works. Benjamin Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols springs to mind, as does the Fantasia on Christmas Carols, by Vaughan Williams for baritone, chorus, and orchestra. Then there was the Carol Symphony composed by Victor Hely-Hutchinson whose music is largely forgotten today, though he was once a big name in the early days of the BBC.

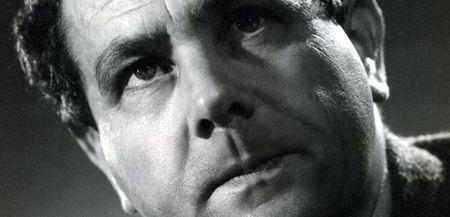

Gerald Finzi.

Gerald Finzi.

In the world of classical music, one Christmas work stands above all others. It’s Bach’s Christmas Oratorio which tells the entire Christmas story. Composed in 1734, the oratorio is in six sections and was cobbled together from earlier works. It runs for nearly three hours and each section was intended for performance on one of the feast days associated with Christmas. There’s a good recording on YouTube by Concentus Musicus Wien conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt although I find Harnoncourt’s conducting style somewhat irritating. The film was made in 1972 and shows its age. But so do I, so I can hardly complain.

The other important Christmas work is the Weihnachtshistorie (“Christmas Story”) by the German baroque composer Heinrich Schütz who was born a hundred years before Bach. It runs for only about forty-five minutes but musically it belongs to another age. There’s a compelling performance of this work on YouTube given by the Monteverdi Choir of Würzburg. And this brings me rather conveniently to the first offering this week, because it’s sung by the same excellent choir.

Max Bruch (1838-1920): Gruss An Die Heilige Nacht, Op 62. Monteverdi Choir, Mainphilharmonie Würzburg cond. Matthias Beckert (Duration: 07:39; Video: 360p)

Bruch is best known for his First Violin Concerto and the Scottish Fantasy for violin and orchestra. In his time, Bruch was more associated with choral music and this work (“Greeting to the Holy Night”) which dates from the 1890s shows him at his best. The music is scored for contralto solo, choir, organ and orchestra and it’s both joyous and uplifting. Sometimes there are moments of rich, luminous harmony and the music sounds more like that of Mahler or Richard Strauss. It is compelling music of remarkable beauty and ends in a spirit of serene, radiant happiness. It would make a wonderful ending to Christmas Day.

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976): A Ceremony of Carols. Svetlana Belaya (sop), Tonica Children’s Choir (Minsk, Belarus), Eugene Galtsov (pno) cond. Alexey Snitko (Duration: 14:34; Video: 1080p HD)

This is not a performance for purists. For a start, the choir includes both male and female voices whereas the original was intended only for boys’ voices. Secondly, the work was scored for harp yet this performance uses a piano. As a result the magical harp sound is lost, but I enjoyed the gutsy performance and the rich sound of these young Belarusian singers.

In 1942, after three years in America, Britten began a month-long voyage to Britain on a Swedish cargo ship. It must have been a hazardous undertaking because U-boat activity in the North Atlantic was at its height. On the way, when the ship was berthed in Nova Scotia, Britten visited Halifax and came across a book of medieval poems in Middle English. He set some of these to music during the voyage. The work was originally intended as a collection of unrelated songs but later unified into a single piece, the eleven-movement Ceremony of Carols.

Gerald Finzi (1901-1956): In Terra Pax, Op 39. Alana Grossman (sop), Benjamin Howard (bar), Northwestern University Chorale, Northwestern University Symphony Orchestra cond. Donald Nally (Duration: 13:53; Video 1080p HD)

We don’t hear much of Finzi’s music these days, but his musical language, like that of Elgar and Vaughan Williams, is unmistakably English. This pastoral, nostalgic piece is a setting of two verses of a poem by Robert Bridges which the composer places before and after St Luke’s account of the angels’ appearance to the shepherds. The work was written in 1954 when the composer already knew he was dying of leukemia.

The origin for In Terra Pax (“Peace on Earth”) goes back to thirty years earlier, when late one Christmas Eve, Finzi visited a favourite church on a hill between Gloucester and Cheltenham. For the rest of his life, he never forgot the sound of the midnight bells joyfully ringing out over the dark, frosty English valleys.