Most woodwind players spend a great deal of their time fretting about reeds. Flute players are lucky because flutes don’t use reeds but all other woodwind instruments do. This preoccupation with reeds is justified because the reed is where the sound begins. You can have the finest clarinet in the world but with a poor reed the instrument will sound awful.

Reeds are usually made from a type of giant cane known to botanists as Arundo donax. In their box, reeds look pretty much the same but there’s no way of knowing what a reed will actually sound like until you stick it in the mouthpiece and try it out. A clarinet player I know used to travel regularly to Paris to buy boxes of reeds direct from the factory and then spend days testing them individually and selecting the best for concert work. A good reed might give him about fifteen or twenty hours’ use and sometimes considerably less. They break easily, too. You’ve got to be pretty dedicated to go through all that palaver.

Oboe and bassoon players have a more difficult time because their instruments use double reeds – two pieces of cane bound together. Not surprisingly double reeds are more expensive. A professional oboe or bassoon reed, bought at a specialist woodwind shop could cost up to thirty dollars. That’s not for a box of them, it’s for one. As a result, some players make their own reeds but it takes a great deal of skill and practice. They then have to spend hours trying them out, which gave rise to the old orchestral joke about how many oboists are needed to change a light bulb. The answer is only one, but he’ll go through thirty of forty bulbs to find the best.

The oboe has a bright and penetrating tone, which is why it’s used to sound the note “A” to which other orchestral instruments tune. It was a popular concerto instrument during the baroque and classical periods but strangely enough, only a handful of rather obscure nineteenth century composers wrote a concerto for the instrument.

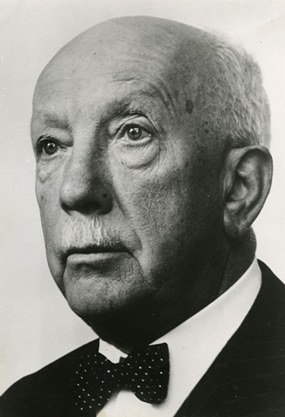

Richard Strauss (1864-1949): Concerto for Oboe in D Major. Marin Tinev (ob), Orchestra of the Trossingen Musikhochschule (Germany) cond. Sebastian Tewinkel (Duration: 20:14; Video 480p)

This was one of the composer’s last works, but it may not have been written at all, had it not been for young Corporal John de Lancie of the US Army, who in civilian life was Principal Oboist with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. In 1945, Corporal Lancie was stationed near the Bavarian winter-sports town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen where Richard Strauss lived. On one occasion he was taken by a friend to visit the composer at his home. The Corporal asked Strauss whether he’d ever considered writing a concerto for oboe, which he hadn’t, but the idea evidently grew on him and by September of the same year Strauss had completed the work.

It is a challenging concerto for the soloist, especially the opening in which the oboe has a solo of fifty-seven bars with hardly a rest between phrases. But for the listener, it’s a charming and approachable work which contains some lovely lyrical music with much interplay between the soloist and the orchestral woodwind. The scoring is light and delicate and at times, especially in the melancholy slow movement, it sounds positively old-fashioned as though the composer is glancing back longingly over his shoulder to a bygone age.

Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826): Concerto for Bassoon. Laurent Lefèvre (bsn), Simon Bolivar Orchestra cond. Pablo Castellanos (Duration: 20:14; Video 480p)

Weber was a contemporary of Beethoven, though sixteen years his junior and best-known for his operas which had a huge influence on those written later in the nineteenth century. Unusually, Weber was also interested in the music of other cultures and was the first Western composer to use a genuine Chinese melody in one of his pieces of incidental music for a play. His instrumental music remains popular today especially the two piano concertos, the horn concerto and the two clarinet concertos. There are also two symphonies, though these are rarely heard.

This concerto was written in Munich in 1811 when the composer was twenty-five. Along with Mozart’s bassoon concerto, it’s considered one of the finest for the instrument. At times it even sounds slightly Mozartian and is thoroughly classical in conception. The composer revised the work some years later, but it is essentially the same piece with brilliant virtuosic writing.

The soloist in this recording was appointed Principal Bassoon in the Orchestra of the Opera National of Paris at the age of only twenty-two, a position he still holds today as well as teaching and giving solo concert performances. But you can be certain that he also spends a great deal of time messing about with reeds.

|

|

|