It’s that time of year again when you’re either out in the streets having a hilarious time throwing water at everyone else or like me, locked up at home hoping the whole wretched business will be over as quickly as possible. But whether we like it or not, it’s festival time again.

In Moscow’s chilly autumn of 1954, a concert was held at the Bolshoi Theatre to commemorate the anniversary of the October Revolution which had taken place in 1917 and known variously as the Great October Socialist Revolution, the Bolshevik Revolution or simply Red October. The concert was conducted by the Bolshoi conductor Vassili Nebolsin who – so the story goes – suddenly realised a few days before the concert that he didn’t have a suitable new work to open the show. Now you’d have thought that all this would have been planned weeks or even months ahead but clearly, it wasn’t.

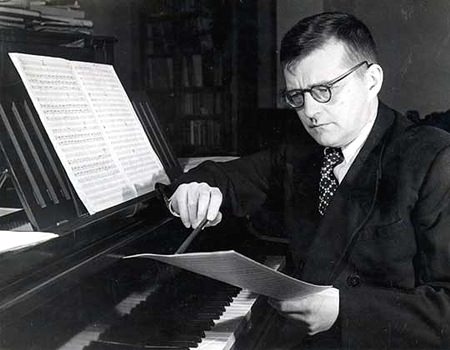

Shostakovich in the 1950s

Shostakovich in the 1950s

Eventually Nebolsin – presumably in a state of some agitation – contacted the composer Dmitri Shostakovich to see if he could come up with something. Shostakovich was one of the leading Russian composers of the time and had a reputation for being able to knock out music at very short notice. And knock it out he did, completing the entire score of Festive Overture within just three days.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975): Festive Overture, Op. 96. Korean Broadcasting System Symphony Orchestra, cond. Hahm Shin-Ik (Duration 06:46, Video: 720p HD)

In Stalinist Russia, music had to be approved by the government and Shostakovich ran into trouble as early as 1936 with his opera Lady Macbeth of Minsk. It was derided in the government press as being “formalist, coarse, primitive and vulgar.”

The same year saw the beginning of the so-called Great Terror, in which many of the composer’s friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed for thought to being opposed to the regime. Not surprisingly, Shostakovich kept a low profile, at least until the first performance of his Fifth Symphony in 1937. It was musically more conservative than his earlier works and deemed acceptable by the authorities. The first performance in Leningrad was a phenomenal success and evidently had a powerful emotional effect on the audience.

Stalin had died in 1953 and perhaps the feeling of joy that we hear in the Festive Overture of 1954 reflects Shostakovich’s sense of relief that a dark episode in Russian history had drawn to a close. The music bears more than a passing resemblance to Glinka’s Russlan and Ludmilla overture in that it has the same kind of mood, style and tempo. Some of the themes in the Festive Overture were lifted out of the ill-fated opera Lady Macbeth of Minsk which now, incidentally is an established part of the repertoire.

The overture demands orchestral playing of the highest calibre and this Korean orchestra gives a spirited performance. This sizzling, exciting music is brilliantly orchestrated and the tension hardly lets up: it’s a breathless race to the finishing line. In some ways, the overture is slightly over-the-top, bordering on vulgarity but I suspect that this was exactly what the composer intended.

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936): Roman Festivals. National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain cond. Vasily Petrenko (Duration: 26:23, Video: 720p HD)

Respighi settled in Rome in 1913 and he’s best known for three symphonic poems: The Fountains of Rome (1916), The Pines of Rome (1924) and Roman Festivals. The third work was first performed in 1929 by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under Arturo Toscanini. It’s the longest and probably the most difficult of the three, both in terms of orchestral writing and its demands on the listener. But don’t let that put you off, because it contains some exhilarating music.

In the first movement (Circuses) Respighi creates an almost photographic sound-picture of an imperial Roman event in which condemned Christian martyrs are thrown to wild animals. We hear the animals grunting, a hymn from the desperate martyrs and the sounds of devastating carnage as the Roman spectators howl with excitement. Compared to this horrific spectacle, Pattaya Songkran is almost sedate.

The second movement (Jubilee) depicts medieval pilgrims arriving in Rome as church bells resound through the city. The third movement (Harvest of October) describes the celebrations that follow the harvest and in the final movement (Epiphany) Respighi portrays a teeming throng of merry-makers packed into the Piazza Navona on the night before Epiphany. The entire work is intensely visual and cinematic. As John Mangum of the New York Philharmonic wrote, it’s “like a soundtrack without a film.”

The NYO gives a remarkably fluent performance of this demanding work under the young Russian conductor Vasily Petrenko who lives in the Wirral Peninsula in Northern England. As well as being an internationally acclaimed conductor, he’s also a football fan and apparently an enthusiastic supporter of Liverpool Football Club.