If you are over a certain age, you may recall a recording that was released in the 1950s and remained popular for many years afterwards. The Singing Dogs was not, as some people probably assumed at the time, a canine barking troupe but was actually a recording project by Carl Weismann, an amateur Danish ornithologist who spent much of his time recording bird calls.

In the 1950s, tape recording was pretty much in its infancy having been developed in Germany during the previous decade. One of the major advantages of using tape was that with the aid of a razor blade, some sticky tape and an editing block you could literally cut out any unwanted sounds. On many occasions, Weismann had to remove intrusive dog-barks from his bird recordings, and he eventually came up with a novel idea for using all the lengths of wasted tape.

Wandering around the streets of Copenhagen, Weismann made dozens of recordings of various dogs barking at different pitches, then he carefully spliced together the most suitable, giving the impression that the dogs were actually barking out a melody. It must have been an arduous and time-consuming task, but with the assistance of record producer Don Charles who supplied the backing tracks, the first record was released in 1955 and eventually became a huge hit in Europe and America.

It’s just occurred to me that if you are a dog person you might be under the impression that this week’s column has a canine theme. Well, I’m afraid that I have misled you and it’s actually about Danish classical music. I’m terribly sorry if this revelation has ruined your day, but sometimes life can be a challenge.

The first Danish composer with any claim to greatness was the seventeenth-century Dieterich Buxtehude. History doesn’t record whether or not he had a dog, but his music made a great impression on Bach. Ask any concert-goers to name a Danish person who wrote music and they’ll probably come up with Carl Nielsen, generally considered to be the country’s greatest composer.

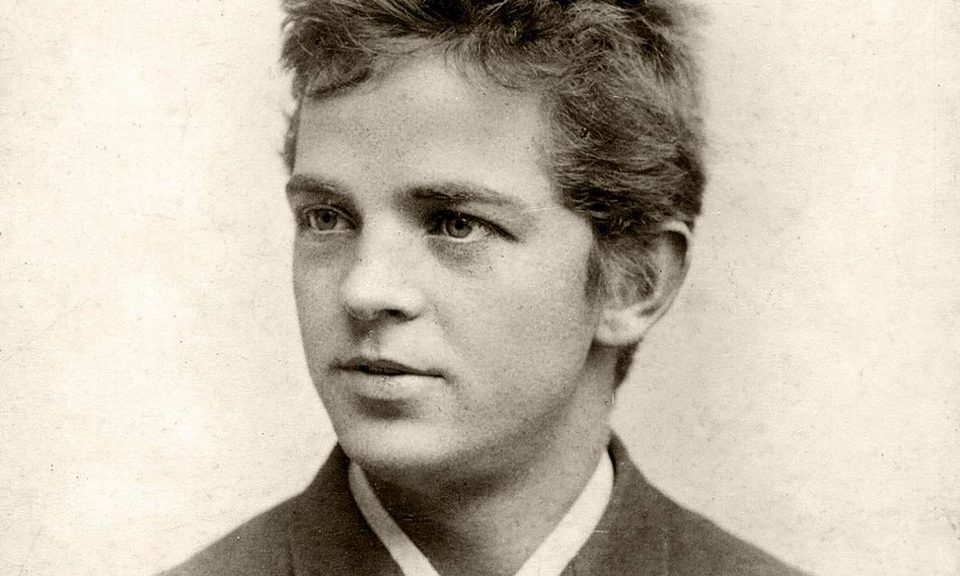

Carl Nielsen (1865-1931): Aladdin Suite Op. 34. Danish National Symphony Orchestra cond. Clemens Schuldt (Duration: 10:36; Video 1080p HD)

Nielsen achieved his first success with Suite for Strings (1888) but by the time he started to write the music for Aladdin he was already an established musician. It was intended for a new production to be performed at The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen in February 1919. Nielsen composed much of the music in Denmark’s seaside town of Skagen during the summer of 1918. The original score runs for over eighty minutes but unfortunately the rehearsals were marred by endless clashes between Nielsen and the director Johannes Poulsen. As it turned out, the production was not much of a success and it closed after only fifteen performances.

The composer often conducted various movements from Aladdin on his concert tours.

Following a major heart attack, Nielsen died in a Hamburg hospital surrounded by his family who had dutifully assembled in his room. His last words to them were evidently “You’re standing there as though you’re waiting for something.”

Hans Christian Lumbye was a contemporary of his namesake, the more well-known but slightly peculiar Hans Christian Andersen. As a young man, Lumbye played trumpet in a military band and at the age of nineteen joined the Horse Guards in Copenhagen. He was also a talented violinist and after hearing a Viennese orchestra play music by Johann Strauss the Elder, he decided to set up a similar orchestra of his own and then started composing waltzes, polkas, mazurkas and gallops, blatantly copying Strauss’s musical style. His music became so popular that the composer eventually earned the nickname “The Strauss of the North”.

For thirty years, Lumbye and his orchestra were associated with the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, where he was the music director and resident composer. He’s best known for his light-hearted compositions, many of which like the Champagne Galop use sound-effects.

The Copenhagen Steam Railway Galop was written in 1847 to celebrate the inauguration of the first Danish railway line between Copenhagen and Roskilde. With the aid of bells, whistles, scrapers and assorted percussion instruments, the music recreates the sounds of a train chugging out of a station and eventually coming to a halt at its destination. Perhaps it all seems a bit simplistic by today’s standards, but in the nineteenth century these jolly sound effects must have delighted the audiences of the day.

|

|

|