Every one of the countless number of Yamaha motorcycles sports the company’s famous logo. If you look at it closely, it should be obvious that it’s an image of three overlaid tuning forks. This might seem a curious choice for a motorbike but it reminds us that when the Yamaha Company was established in 1887 it produced pianos and reed organs. It wasn’t until the mid 1950s that it started making electronic equipment and motor bikes.

The Yamaha story began when a watchmaker named Torakusu Yamaha tried his hand at building a reed organ in 1887. Unfortunately, the instrument was criticised for being out of tune but undaunted, Torakusu went back to the drawing-board and began to study music theory and tuning. After four months of endless daily labour, he finally built a successful reed organ with the help of tuning forks, which had been invented in England 170 years earlier by a British musician named John Shore.

Oddly enough, the tuning fork logo didn’t appear on Yamaha products until 1967 even though the company had been producing pianos for years. Today, Yamaha also makes a wide range of fine orchestral instruments and their brass and woodwind instruments are especially popular. Japan has become the producer of top-or-the-range instruments including saxophones from Yanagisawa and flutes from Miyazawa and Nagahara. You may be interested to know that one of the Nagahara professional flutes is made of 18K gold and comes at the eye-watering price of $33,000.

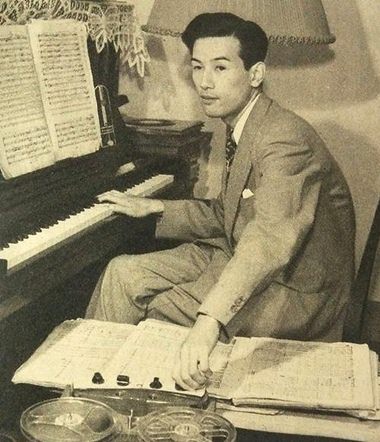

For some reason, we don’t seem to hear much music from Japanese composers, although there are plenty of them. Since the latter half of the nineteenth century, Japanese composers have looked towards western musical culture, often drawing on elements from Japanese traditional music. K๔mei Abe was one of the leading Japanese composers of the last century. His First Symphony of 1957 is a good introduction although it’s a curious mix of musical styles. The incredibly prolific Toshiro Mayuzumi composed more than a hundred film scores and if you’d like an entertaining musical experience, seek out his Concertino for Xylophone and Orchestra. Kunihico Hashimoto was one of the leading Japanese composers in the twentieth century, whose music reflects elements of late romanticism and impressionism, as well as of the traditional music of Japan.

Yasushi Akutagawa was a student of Hashimoto at the Tokyo Conservatory of Music. His lucky break came in 1954 when he illegally entered the Soviet Union and became friends with Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian and Dmitri Kabalevsky. He was the only Japanese composer whose music was officially published in the Soviet Union at that time. His 1950 Music for Symphony Orchestra certainly owes a debt to Shostakovich and the Triptyque is a spiky work which shows influences of Stravinsky and Prokofiev. Incidentally, Akutagawa was one of the few composers who was also a popular presenter of television shows.

Takemitsu is currently Japan’s best-known composer but his fame came about by someone else’s mistake. When Stravinsky visited Japan in 1958, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation NHK arranged for him to hear some of the latest Japanese music. A recent recording of Takemitsu’s Requiem for String Orchestra was played by mistake but Stravinsky insisted on hearing it to the end. He greatly admired the work and later invited the young composer to lunch. Takemitsu later received a commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation, no doubt thanks to Stravinsky who must have put in a good word for him.

Takemitsu was virtually self-taught and began to compose at the age of sixteen. He gradually acquired orchestration skills and learned how to combine elements of Japanese and Western ideas, creating a sound which was entirely his own. This work was commissioned by Carnegie Hall in celebration of its 100th anniversary. Although it is effectively a concerto for percussion it is not intended as the composer explained, “to show off the virtuosity of the soloists. The ruling emotion of the work is one of prayer.”

The title comes from a poem by Makoto Ooka, a Japanese poet and friend of the composer. And incidentally, you’ll need to give the piece some time to get going, but when it does you’ll enter Takemitsu’s highly personal and evocative sound-world, perhaps inspired by the music of Messiaen and Ligeti. He uses some exotic instruments too but if so-called “modern music” isn’t normally your idea of fun, do give this compelling work a try.

To return to Mr Yamaha and his tuning forks, I sometimes wonder how many Yamaha motor bike owners have the remotest idea what the logo represents. Not many, I suspect.

|

|

|