A week or so ago, I attended a classical chamber concert at which a group of people in the audience began applauding after every movement. Not just once, but throughout most of the concert. They must have wondered why nobody else joined them in their applause. No one corrected them, at least, not as far as I could see, but that would have been bad manners anyway. One of today’s Golden Rules of classical music concert etiquette is that one doesn’t clap between movements. We’ve all been to one of those concerts where someone starts clapping at an inappropriate moment, causing a general feeling of discomfort or annoyance among everyone else. More importantly it disturbs the flow and continuity of the music.

At a concert a couple of years ago during the performance of a Bach concerto, there was a tentative ripple of polite applause from some students the back of the hall at the end of the first movement. One of the concert promoters leapt from his seat and gestured wildly at the offenders, thus making himself more of a distraction than those he was foolishly and misguidedly reprimanding. Anyway, the subject of applause last week got me wondering about where the concept began. When and why did people decide that slapping their palms together could be used to show approval?

The word “applause” (as you might have guessed, or possibly knew already) comes from the Latin word applaudere which simply means to clap or strike something. No one knows the origin of clapping though it certainly goes back well before the ancient Romans and if found in many different cultures. A study by Alison W Fletcher of the University of Chester discovered that chimpanzees sometimes clap but usually because they want to direct attention to themselves or want food. She found that clapping is quite common among adult chimpanzees but less so in younger ones. It is common in many human societies to attract attention by clapping. Interestingly, clapping to attract attention is common in some countries, especially in Asia.

The idea of clapping to show approval is considered by some psychologists to be a learned behavior and although babies clap before the age of one, not to show approval but probably just to make a noise. It’s possible that the concept of clapping goes back to the earliest humans, or possibly even before them. Professor Bella Itkin of DePaul University’s Theatre School believes that clapping is one of the earliest human activities. It may have been used initially to scare away unwanted animals rather than to show approval. However, in the Bible, Psalm 47 includes the passage: “O clap your hands, all ye people; shout unto God with the voice of triumph.” This is clearly applause to display acclaim and the Psalms date from before the fifth century BC.

Megan Garber writes, “Applause, in the ancient world, was acclamation. But it was also communication. It was, in its way, power. Applause, participatory and observational at the same time, was an early form of mass media, connecting people to each other and to their leaders, instantly and visually and, of course, audibly.” The use of organised applause to show approval could well have begun with the ancient Greeks. Certainly, it was widespread in the Roman Empire in which there were set rituals at public performances to express degrees of approval: snapping the finger and thumb or clapping with the flat or hollow palm. I read somewhere that when the dictator Joseph Stalin entered conferences in Soviet Russia, audience members who didn’t clap for long enough would be arrested.

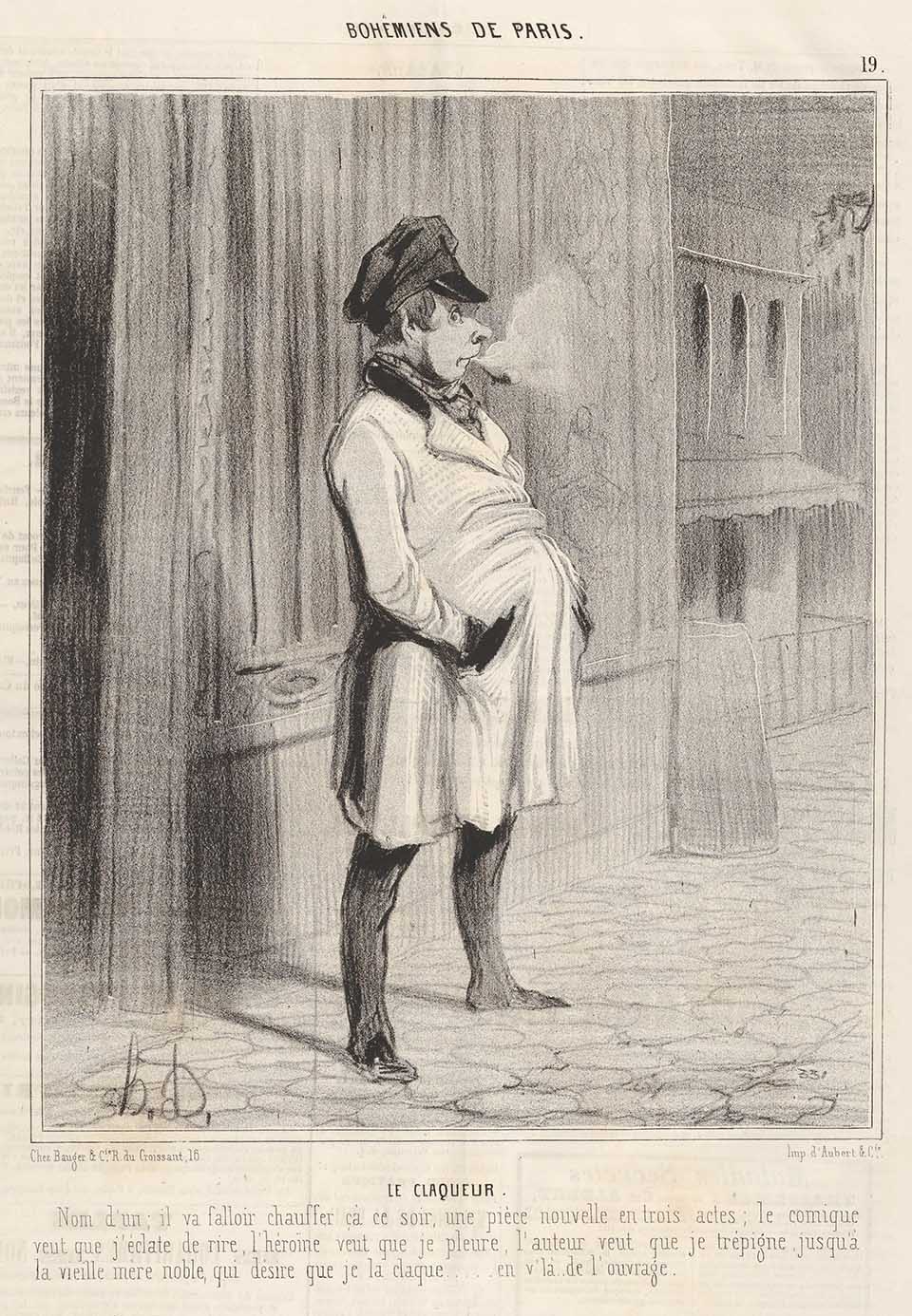

In the theatre and opera house, applause became so integral to the performance that people were sometimes paid to clap or cheer at appropriate places during a performance. The practice of hiring people to applaud dramatic performances was common in Roman times.

The 16th century French poet Jean Daurat revived the idea and gave away free tickets to his plays to those who would clap when instructed. By the middle of the 19th century the practice of using claques, as these hired clappers were called, had taken hold in almost every opera house in Europe along with the practice of hiring people who would shout for encores or laugh loudly at any jokes. In 1820 an agency opened in Paris to manage and supply claqueurs for any occasion. Today we consider the practice a bit quaint but the concept is similar in some ways to the use of “laugh tracks” and “applause tracks” that have been used in TV shows since the 1950s. TV studios invariably used applause light boxes to ensure the audience applauded when desired.

“Up until the beginning of the twentieth century”, writes the American music critic Alex Ross, “Applause between movements and even during movements was the sign of a knowledgeable, appreciative audience, not of an ignorant one.” In the 18th century, applauding during a concert was encouraged. We know from letters written by Mozart to his father that he enjoyed having his music bring interrupted by an enthusiastic audience and purposely wrote orchestral passages that would cause the audience to erupt in spontaneous applause. “Right in the middle of the first allegro,” Mozart once wrote, “came a passage that I knew would please, and the entire audience was sent into raptures – there was a big applaudissement – and as I knew, when I wrote the passage, what good effect it would make.”

At the first performance of Brahms’s First Piano Concerto in 1858 the composer knew things were not going well because there was no applause after the first movement. On the other hand (if you’ll excuse the irresistible pun), Mendelssohn explicitly asked that his Third Symphony be played without a break to avoid what he described as “the usual lengthy interruptions”. It’s thought that the practice of keeping quiet between movements may have originated in Germany during the late nineteenth century when there was a move towards a more passive audience.

I remember once hearing a thrilling performance of a Beethoven piano concerto in which the dramatic end of the first movement surely must have been composed to elicit an audience reaction. I cannot have been the only one who wanted to release my excitement and applaud or even cheer the soloist. But of course, nothing of the sort happened apart from the usual coughing and shuffling in an awkward self-imposed silence. In Beethoven’s time there would probably have been a standing ovation.

It’s easy to understand how newcomers to classical music will break into spontaneous applause at such moments. Perhaps it’s time to change the way we think about concerts. Even so, to rebuke people for showing their appreciation is sheer bad manners. Of course, this rule of etiquette generally applies only to classical concerts. In jazz concerts, it is customary to applaud individual improvised solos during the music and sometimes even in opera there will audience reaction after a particularly rewarding aria or other set piece.

Steve Reich (b. 1936): Clapping Music (1972). Performed by composition students at the College of Music, University of Colorado at Boulder (Duration: 04:54; Video: 480p)

In this piece, it’s the performers, rather than the audience, who do the clapping. Steve Reich is one of the pioneers of minimalism and he’s had a huge influence on contemporary music. He experimented with a concept known as phase shifting, in which one or more repeated phrases plays slower or faster than the others, causing it to go “out of phase.”

This creates new musical patterns in a perceptible flow. Clapping Music was written in 1972 and originally for just two performers. Without getting into technical details, it uses a development of phase shifting and consists of just twelve measures (bars) each of which is played eight times. One performer (or group of performers) claps a single rhythm throughout the piece. In the first measure, the second performer claps the same rhythm (eight times of course) but in the next measure the rhythm shifts by one eighth note to the right. This process continues throughout the piece until the thirteenth measure when the second performer is inevitably clapping the same rhythm as the first, drawing the piece to its logical and inescapable close. It’s elegantly simple but strangely mesmerizing as the rhythmic patterns shift out of phase with each other.

Although originally written for two performers, Clapping Music is invariably performed by a group, which to my mind makes for a much more satisfying sound. If you want to brush up your music-reading skills, you can find the music and follow the scrolling score simultaneously on YouTube. Then you can clap the music along with the performers. It’s good fun, but you have to think quickly.