Some of the most rewarding music can often be found in the byways of musical history rather than on the historical super-highway. Even as a schoolboy, I was always more fascinated by the so-called “minor” composers than by the big names, much to the irritation of my music teacher who held the view that one should first become acquainted with the standard repertoire. You know the kind of thing; learn the Beethoven and Brahms symphonies first before wasting time with obscure blokes like Heller, Volkmann, Litolff and Raff. But perhaps I just wanted to be different. After all, I played the cello and cellists are supposed to be different.

Although the cello has always played an important role in the orchestra, few solo concertos were written for the instrument before the nineteenth century. Admittedly, there are a few early cello concertos by Joseph Haydn, Luigi Boccherini, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and the prolific Antonio Vivaldi – who churned out twenty-five of them – but at the time, the cello wasn’t really considered a solo instrument. Perhaps the playing technique had not developed sufficiently for the technical demands of a concerto. Or perhaps a single cello couldn’t produce sufficient volume to carry above the sound of an orchestra, especially in its low register.

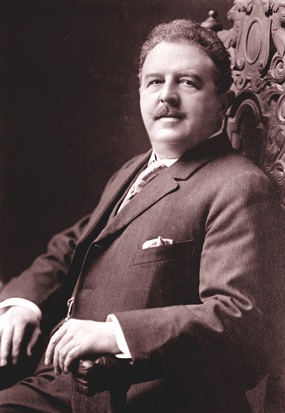

Victor Herbert.

Victor Herbert.

Whatever the reason, the cello wasn’t recognised as a solo instrument until the mid-nineteenth century with notable concertos by Schumann (1850), Saint-Saëns (1872), Lalo (1876) and Dvořák (1894). Even so, compared to the vast number of violin concertos, those for the cello were pretty thin on the ground.

Incidentally, you may not know that Dvořák wrote two cello concertos. The famous one is actually the second concerto although rarely described as such. The composer wrote the first one thirty years earlier but never got around to completing the orchestration.

Victor Herbert (1859-1924): Cello Concerto No 2. John Michel (vc), Yakima Symphony Orchestra cond. Lawrence Golan (Duration: 21:44, Video: 1080p HD)

“Victor who?” you may well ask. Few people needed to ask such a question at the turn of the twentieth century when Victor Herbert was a big name, best known for many successful operettas such as Naughty Marietta and Babes in Toyland. If the second one sounds familiar, it was the title of a 1961 Walt Disney Christmas movie based loosely on Herbert’s 1903 original.

Born in Ireland and raised in Germany, Herbert began his career as a cellist in Vienna but later he moved to America where his career blossomed as a conductor and teacher. He conducted the Pittsburgh Symphony from 1898 to 1904 and founded the Victor Herbert Orchestra, which he conducted for the rest of his life.

Herbert was a prolific composer and wrote two operas, over forty operettas and many works for orchestra, band and solo instruments. The cello concerto is one of the few of his works still in the repertoire. It was first performed in March 1894 by the New York Philharmonic with the composer as soloist. There’s an interesting connection here, because Victor Herbert evidently drew some of his inspiration from Dvořák’s New World Symphony which had been first performed the previous year. He even used the same key – E minor. Dvořák had previously considered the cello unsuitable as a concerto instrument, but was so impressed by Herbert’s music that he had a change of heart and within months, set to work writing his own.

The inspiration may have come from the New World Symphony but Herbert’s musical style is very different and if anything, a little more modern. We hear shades of Herbert’s popular operetta style in the lovely lyrical slow movement. As the critic Lawrence Hansen wrote, it’s “an example of a lesser composer drawing inspiration from a greater one and, in turn, inspiring his mentor”.

Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978): Cello Concerto in E Minor. Denis Shapovalov (vc), Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra, cond. Vladimir Fedoseyev (Duration: 33:52, Video: 1440p HD)

Aram Khachaturian has remained one of the most important Russian composers of the twentieth century. Between 1936 and 1946 he wrote three concertos for piano, violin and cello respectively. Oddly enough, the cello concerto is in that same key of E minor and although it was the last of the three to be written, it was the first one that Khachaturian had seriously considered. Even so, it’s probably the least-known of the three and is said to echo Khachaturian’s painful experiences of wartime.

Khachaturian is one of those composers who have their own distinctive personal sound and while to modern ears, the work sounds perfectly acceptable with its many reminders of Armenian folk songs and dance rhythms it wasn’t always thus. In 1946 the work attracted the displeasure of the Russian authorities because it was considered too “formalistic”, with the result that Khachaturian was unceremoniously given the old heave-ho from the Composers Union.