As any movie buff will be delighted to tell you, this is one of the most well-known misquoted lines in cinema. It’s usually attributed to the leading character played by Humphrey Bogart in the 1942 movie Casablanca, but he didn’t actually say it. And neither evidently, did anyone else. Even so, it’s interesting to ponder why we enjoy hearing familiar things over and over again.

Classical concert promoters know only too well that one way to fill a concert hall is to include music that people know. David Huron is a musicologist at Ohio State University and he’s estimated that when people listen to music, ninety percent of it is music they’ve heard before.

Repeated patterns at the Palace of Versailles. (Photo: Urban)

Repeated patterns at the Palace of Versailles. (Photo: Urban)

Repetition also occurs within the music itself. The majority of popular songs and folk songs include a chorus, usually repeated several times. Bruno Nettl has suggested that repetition is one of the few things that is common to music the world over. It’s even been discovered that our brains show more activity in their emotional regions when the music we’re listening to is familiar, regardless of whether or not we actually like it.

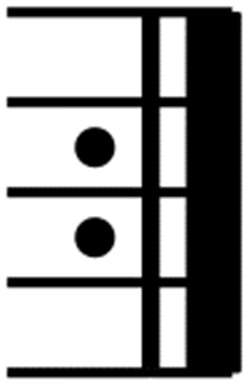

A musical repeat sign.

A musical repeat sign.

Repetition became especially important during the classical era of European music when greater emphasis was placed on form and shape. You can see the same obsession with the repeated patterns and formal elegance in classical French gardens such as the Gardens of Versailles, a style which was subsequently copied by other European courts.

In eighteenth century symphonies and other instrumental music large sections of music are traditionally repeated. This not only helped the audience absorb the melodies but also was an easy way to lengthen the music without undue hard work, because the composers simply inserted repeat marks into the score. At the same time, the rondo was a popular form in which the same melody, or a variation of it, was repeated several times during the piece.

Repetition is also used within melodies and musical phrases. At one point in Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No 3 the melody includes the note G played twenty-four times in succession. In Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (the one that opens with the famous four-note motif) the entire first movement is based on repetition. Perhaps this might account for the work being one of his most popular symphonies.

Far be it from me to bore you with technicalities but the word ostinato (think “obstinate”) is used to describe a motif, phrase or rhythm that persistently repeats during the music. The device has been popular with composers for years and it’s used dramatically in two works by Maurice Ravel and Gustav Holst. Ravel’s Boléro was actually intended for a short ballet and it’s probably the world’s most frequently played piece of classical music.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937): Boléro. Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Gustavo Dudamel (Duration: 17:22; Video: 720p HD)

Ravel had been commissioned to write a ballet by the Russian actress and dancer Ida Rubinstein and he got the idea for this piece when on holiday in Saint-Jean-de-Luz on the French Basque coast. The music is dominated by a relentless snare-drum ostinato rhythm which begins almost inaudibly, played near the rim of the drum and accompanies a hypnotic wandering melody that repeats throughout the piece. Gradually the volume and texture increase and by using his own brand of masterful orchestration, Ravel builds the work up to a thrilling climax.

The first performance was in 1928 and acclaimed by a shouting, stamping and cheering audience. It must have gone down well. Incidentally, the dance known as the bolero has three beats to the bar and originated in eighteenth century Spain. It’s totally unrelated to the Cuban dance of the same name.

Gustav Holst (1874-1934): Mars – the Bringer of War (The Planets). BBC Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Charles Mackerras (Duration: 07:22; Video 480p)

Holst began writing his massive suite The Planets in 1914 and completed the work two years later. The first movement Mars: The Bringer of War has been described as “the most devastating piece of music ever written”. The ostinato consists of an ominous rhythmic pattern which dominates the entire movement. At the opening, the strings play this rhythm col legno which involves hitting the string with the wood of the bow, producing an eerie percussive sound. The movement builds up tension throughout, with a menacing quieter middle section. This is not a battle with bows and arrows; it’s about the horrors of mechanized warfare, emphasized by the composer’s use of pounding percussion, grinding, clashing harmonies and of course the relentless ostinato. Gradually the music lumbers towards its inevitable climax, leaving us with a sense of poignant loss and desolation.

Oh, and just in case you’re wondering what Sam was requested to play again, it was the immortal song As Time Goes By which had been written ten years earlier.