“To a summer’s day?” I hear you murmur. “Thou art more lovely and more temperate. Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date…” Or perhaps I don’t hear you murmuring anything, if you’re not familiar with the most well-known and most quoted of William Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets. They were published in 1609 and touched on eternal themes such as the passage of time, mortality, love, beauty, infidelity and jealousy. Interestingly, there is evidence that Shakespeare never intended the poems to be published. Most of them are addressed to a young man, a fair youth whose identity is uncertain though there has been no shortage of theories. Perhaps the most likely is that the “fair youth” was Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton. On the other hand, it might have been someone else. In this particular poem, Shakespeare asks the “fair youth” how his beauty can adequately be described. He also refers to the timeless quality of poetry and rejoices in the joy of summer.

The “summer” theme dominates the well-known thirteenth century English song entitled Sumer is icumen in. Strictly speaking, it isn’t actually a song at all, but a vocal piece called a rota which is similar to a round although slightly more complicated. Although it sounds distinctly medieval, the music still speaks clearly to us. It’s thought that the song might have been composed by another William; a composer, copyist and sub-deacon at the priory of Leominster in Herefordshire. The words are in the old Wessex dialect of Middle English which is so different to modern English that they are largely incomprehensible. The title of course, means “summer is arriving” and the lively song rejoices in the coming of the warm weather to the English countryside and especially the arrival of the cuckoo. There are references to bleating ewes and flatulent goats, though the medieval lyrics use more rustic terminology.

As far as we know, it’s the earliest known European composition that celebrates the coming of summer. Many more were to follow, including some of the madrigals of the sixteenth century and the art-songs of the nineteenth, celebrating what Longfellow later described as “that beautiful season.” The nineteenth century in particular, when composers and artists were anxious to grasp at all things connected with nature saw the rise of music celebrating summer.

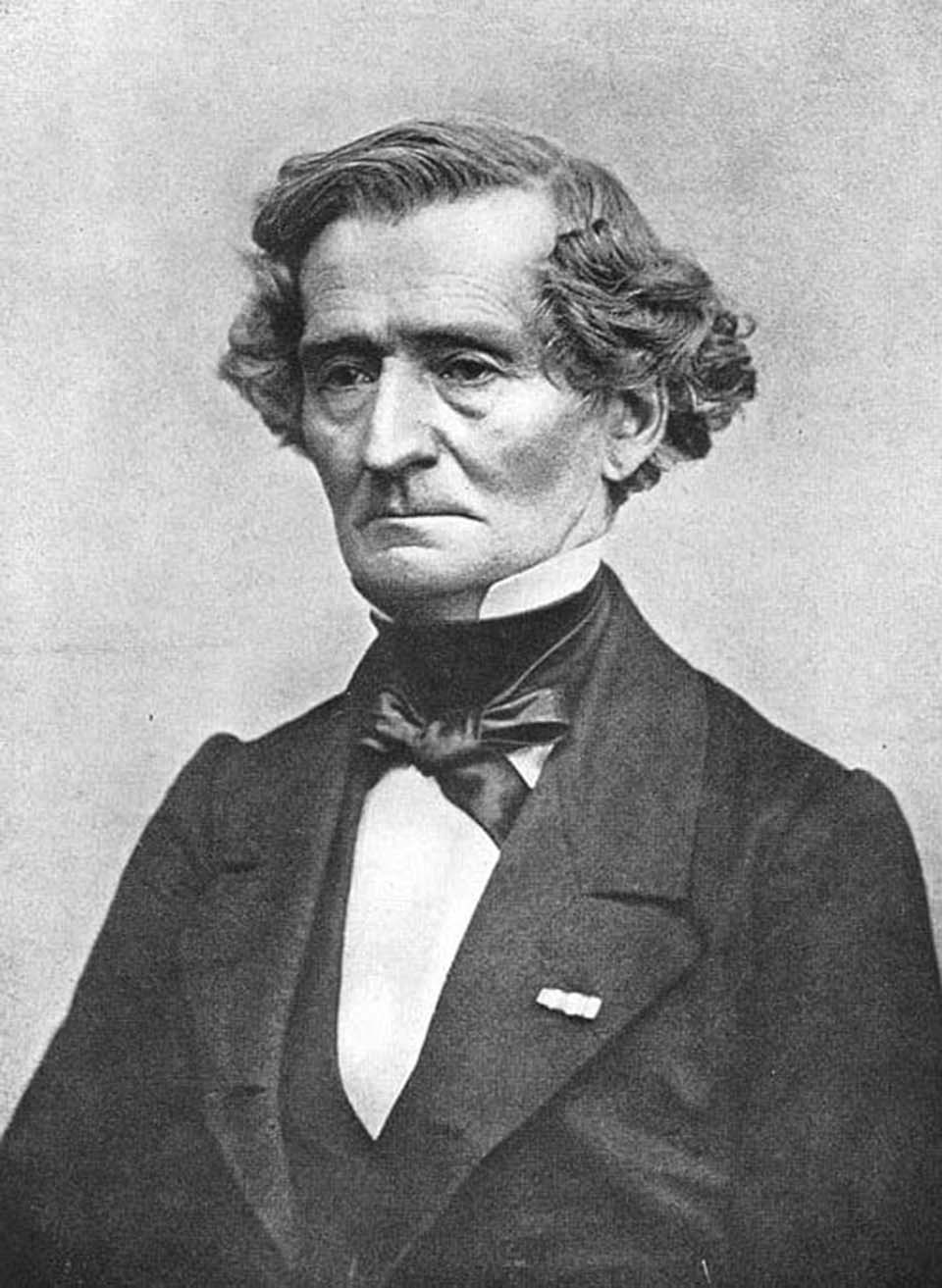

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869): Les Nuits d’Eté. Joyce DiDonato (mezzo-soprano); National Youth Orchestra of the USA cond. Sir Antonio Pappano (Duration: 30:20; Video: 480p)

I’m guessing here, but I wouldn’t mind betting that apart from operatic arias, this work is probably the first example of a collection of songs for voice and orchestra, paving the way for those of Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. Summer Nights (or Nights of Summer) is a setting of six poems by the French art critic, poet and fiction writer Théophile Gautier. Berlioz originally composed the work for voices and piano but in 1856 he wrote the full orchestral score which is the version usually heard today. Strangely enough, this orchestral version was never performed in its entirety during the composer’s lifetime and the work was neglected for years. During the 20th century it was revived and became one of Berlioz’s best-loved works, for the music is charming, attractive, very French and quite light-hearted for Berlioz who is more often associated with grander, more serious stuff. This is an interesting performance too, given at one of the BBC Proms by America’s top youth orchestra conducted by the British-Italian conductor Sir Antonio Pappano who in 2023 is due become Chief Conductor Designate of the London Symphony Orchestra.

Frederick Delius (1862-1934): In a Summer Garden. Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra cond. Sir Andrew Davis (Duration: 16:32; Video: 720p HD)

This is a fantasy for orchestra composed in 1908 and first performed in London the same year. Although Delius is always regarded as an English composer, he had German parents (hence the rather un-English name), he lived in the United States, travelled in France and Germany as well as other parts of Europe and finally settled in France. In this work, the garden in question is not in England as you might expect, but the composer’s own garden at his country home in Grez-sur-Loing, a commune about thirty miles south of Paris. But you’d never guess the French connection, for the music sounds completely English in its tonality and sound-world. I know it’s a curious expression but to me this is intensely “visual” music: colourful, expressive music of quickly changing hues and moods, almost like a series of fleeting snap-shot visual impressions. In the published score, there’s an anonymous quotation which give us some clues about the music: “Roses, lilies, and a thousand scented flowers. Bright butterflies; flitting from petal to petal. Beneath the shade of ancient trees, a quiet river with water lilies. In a boat, almost hidden, two people. A thrush is singing in the distance.”

|

|

|