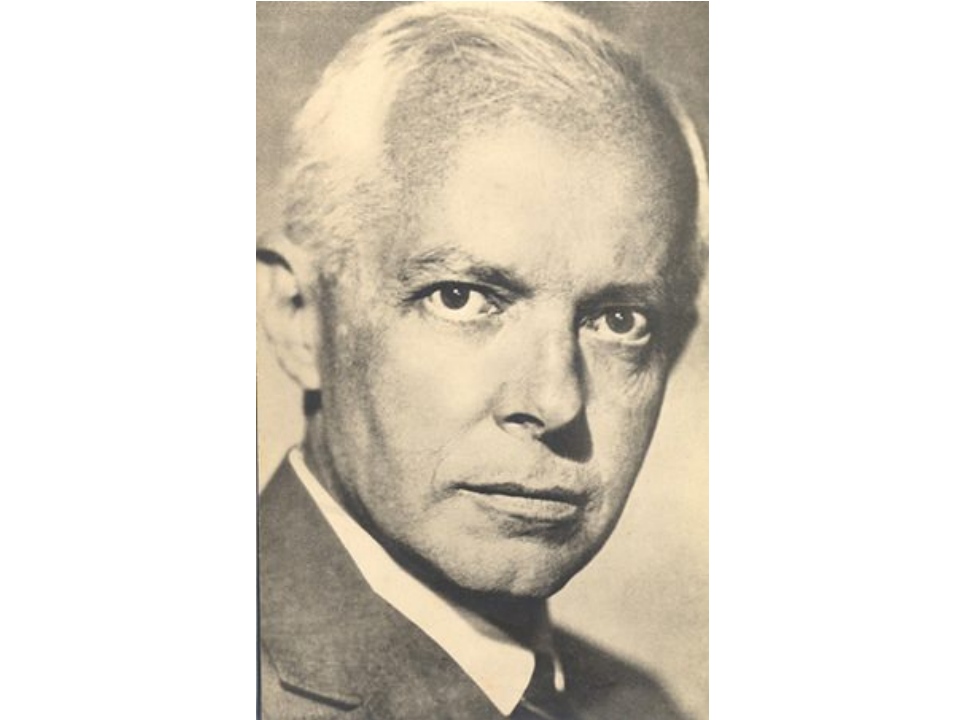

There was a time, not so long ago when much of Béla Bartók’s music seemed terribly modern-sounding. As a schoolboy during the last century, I remember being thrilled on hearing for the first time, a recording of his Divertimento for Strings. It was the sheer sound of the music that was so exciting.

The Bartók string quartets were a bit of a challenge, though today they fall more easily on the ear than they did fifty years ago. Sound is what it’s all about. Like many of the best composers, Béla Bartók (BAY-lah BAR-tohk) had his own particular way with sounds. He created his own musical soundscapes and you can often recognise his personal sounds within seconds.

I suppose much the same could be said of composers like Sibelius, Delius, Debussy, Stravinsky or Vaughan Williams. You can probably think of others who had the ability to build a musical sound-world that is almost instantly recognizable. Many of the finest painters had this same extraordinary skill of visualizing and creating a unique and personal style. Just think how easy it is to recognise a Caravaggio, a Hieronymus Bosch, a Max Ernst, a Salvador Dali or a Paul Cézanne. And you could probably spot a painting by Mark Rothko at two hundred yards.

Although he was well-travelled, Bartók remained in his native Hungary until the declining political situation after the outbreak of World War II. He was opposed to the Hungarians siding with Germany and his anti-fascist views not surprisingly brought him into conflict with the Hungarian establishment. He finally left the country in 1940 and settled in America. But not for long, because within several years, he was diagnosed with leukemia and at that stage, little could be done about it.

During his last years, when he must have realised that time was not on his side, he had a surge of creative energy and composed some of his finest works. One of them was the Concerto for Orchestra, commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky, the conductor of the Boston Symphony.

Béla Bartók (1881-1945): Concerto for Orchestra. The Orchestra of the University of Music Franz Liszt, Weimar cond. Nicolás Pasquet (Duration: 40:04, Video: 1080p HD)

Bartók completed the score of this work on 8th October 1943 and it was performed two months later by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Koussevitzky. The title Concerto might seem rather odd because they are normally for a solo instrument with orchestral accompaniment. Bartók explained that he called the piece a concerto rather than a symphony because each section of instruments is treated in a solo-like manner. It has become Bartók’s best-known orchestral work and if you are unfamiliar with this composer, this is as good a place as any to start. Written in five movements, there are plenty of attractive Hungarian-style melodies, lively rhythms and reflective moments. The talented young students from the University at Weimar give a stunningly good performance.

Leoš Janáček (1854-1928): Taras Bulba. Symfonieorkest Vlaanderen cond. Jan Latham-Koenig (Duration: 23:39, Video: 720p HD)

If Bartók is one of the most singular musical voices of Hungary, then Janáček is probably his Czech counterpart despite the fact that he was born in Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire. Leoš Janáček (LAY-osh yan-AH-chek) had a somewhat daunting personality and as a student he was self-opinionated and unhesitatingly critical of his teachers. In later years, his own students found him to be strict and uncompromising. Nevertheless, he was a tireless worker who composed eight operas, and his early orchestral works show the influence of Dvořák whom he knew personally. But after 1900 Janáček had found his own singular voice and stylistically his later works lie firmly in the twentieth century.

Janáček completed this suite in 1918 and the original idea came from a novel by Nicolai Gogol involving a Cossack military leader named Taras Bulba. The music depicts episodes from a 1628 conflict between Cossacks and Poles and there are three movements rather gloomily entitled The Death of Andrei, The Death of Ostap and The Prophecy and Death of Taras Bulba. But don’t be deterred by the morbid titles because it’s a remarkably satisfying work.

You’ll get a real taste of Janáček’s more mature musical style in the last movement, in which jagged melodies suddenly appear and musical ideas are seemingly thrown around. There are passionate outbursts of sound then sudden romantic moments. It contains some bizarre musical ideas, yet also has the most poignantly beautiful melodies. It also uses one of Janáček’s characteristic harmonic progressions, which you’ll hear over and over again, bringing the work to a thrilling and heroic conclusion. The progression uses a dominant thirteenth chord, which instead of the classical conventional resolution, falls to the chord of the sharpened supertonic with a decorated 9-8 suspension. I just thought you’d like to know.

|

|

|