People have been singing songs for thousands of years and songs can probably be found in almost every culture on Earth. In their simplest form songs are just melodies, usually with words attached. The earliest were almost certainly unaccompanied.

Songs written by classical composers (and here I use the word “classical” in its loosest sense) are fundamentally different from songs in popular and folk cultures. For a start art songs, as they’re often called, are nearly always written for voice and piano, but more importantly they’re musical settings of independent poems which previously existed in their own right. More often than not, art songs are intended for “a classical recital in a relatively formal social occasion”. The last bit is quoted from Wikipedia, because it rather neatly hits the nail on the head.

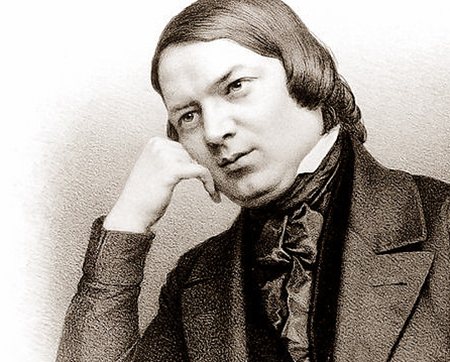

Robert Schumann (circa 1850).

Robert Schumann (circa 1850).

Although art songs had been written for generations, notably by John Dowland and Thomas Campion in England, the Great Age of Song occurred in Germany during the nineteenth century, which is why the German word “lieder” (LEE-duh) is often used to describe them. The enormous flowering of Germanic romanticism provided perfect conditions for the art song to flourish. And flourish it did, especially in the hands of Franz Schubert whose six hundred songs explore a range of romantic ideas. Schubert developed the idea of the song cycle – a collection of individual numbers loosely linked through some kind of non-musical idea, thus paving the way for Schumann, Wolf, and many others.

As the nineteenth century wore on, orchestral music became increasingly popular in Europe partly because more orchestras were appearing in the burgeoning cities. Furthermore, orchestras were slowly shifting from the royal courts to public concert halls. Some composers who had written song cycles for voice and piano arranged their work for voice and orchestra, notably Hector Berlioz and later Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. Of course, the concept of voice with orchestra wasn’t particularly new because it was well-established in opera.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856): Dichterliebe. Matthew Worth (baritone), Shai Wosner (pno) (Duration: 28:47; Video: 1080p HD)

Schumann wrote several song cycles in 1840, notably Dichterliebe (A Poet’s Love), which was to become his best-known. It was composed in a matter of days and consists of sixteen settings of poems by Heinrich Heine, one of the great German writers of the time. Nowadays, the work is nearly always performed by a male singer but it was actually dedicated to the once-famous soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient. She achieved more fame (or possibly notoriety) after her death with two volumes describing her erotic adventures, the second of which explores sexual activities that really shouldn’t be mentioned in a family newspaper. Some people have uncharitably suggested that she made the whole thing up. Even so, the book became Germany’s most famous work of erotic literature (if such it can be called), and was published in English under the quaint title Pauline the Prima Donna. The contents are anything but quaint and if such unwholesome things interest you, an English translation can be read online, but it’s pretty strong stuff. Or so I’m told.

Schumann’s song cycle is chaste in comparison and he takes a novel approach to the setting of Heine’s verses. He adapts the words of the poems to his musical needs, sometimes repeating phrases and often rewording a line of text to give the desired effect. The piano part sometimes reflects the mood of the text, yet at other times it seems that the music and the text are at odds with each other using harmonies that must have seemed quite advanced at the time.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911): Rückert Lieder. Magdalena Kožená (mezzo-soprano), Lucerne Festival Orchestra, cond. Claudio Abbado (Duration: 20:10; Video: 720p HD)

Mahler was one of the great names of the late romantic movement and Rückert-Lieder is a song cycle based on poems written by the German poet and linguist Friedrich Rückert. He was best-known as a translator of Oriental poetry and was a master of thirty different languages. His own poetry was much admired and set by many composers including Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Richard Strauss, Hindemith, Bartók and Berg. As a composer, Gustav Mahler always had a close relationship with song and one of his remarkable skills was the ability to convey subtle emotions with what appear to be relatively simple melodic lines.

Unlike some of his gargantuan orchestral works, this one uses a comparatively small orchestra and Mahler accompanies the lyrical songs with delicate orchestral scoring. The size and instrumentation varies from song to song, but gives the listener a glimpse of the composer’s masterful orchestration skills. This is a fine performance too, with a legendary Italian conductor and a superb Czech soprano.