You may have come across a question-and-answer website called Quora, where people send in questions about almost anything. Some of the questions border on the naïve but I suppose you could argue that all questions are valid, regardless of how obvious the answers might first seem. Anyway, last week someone asked the question “Why hasn’t Britain produced any important composers like Mozart and Beethoven?”

Many years before Mozart was born in 1756, the country now known as Britain had already produced some of the greatest composers in history. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, which covered the forty years between 1558 and 1603, English art and culture reached new peaks of achievement and the period has since become known as The English Renaissance or the Golden Age in British History. England was well-off compared to other nations, with a well-organized and effective government; it was beginning to benefit from trans-Atlantic trade and the period was one of exploration and expansion. The dastardly Spanish Armada was roundly defeated, partly due to a combination of English technical superiority, naval tactics and good luck. These were the days of William Shakespeare and his contemporaries, who revolutionized theatre arts. The period also saw the flowering of English poetry, music and literature as never before. It must have been a wonderful place to live at the time, assuming of course that you were lucky enough to be born into a wealthy or aristocratic family.

During these eventful years, secular and instrumental music became more popular, especially in the home. Queen Elizabeth promoted music and was herself an accomplished instrumental player. At the same time, top professional musicians were employed by the church. Perhaps the greatest of all was William Byrd, who exerted an enormous influence on other composers both at home and abroad. The most popular song writer of the day was John Dowland, whose songs for lute and voice brought him fame throughout Europe. Then there was Giles Farnaby, Thomas Campion, Thomas Morley and one of the most influential, Thomas Tallis who was thirty years older than William Byrd and an eminent figure at the palace and chapel of Queen Elizabeth.

Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585): The Lamentations of Jeremiah I. The Queen’s Six (Duration: 07:37; Video: 1080p HD)

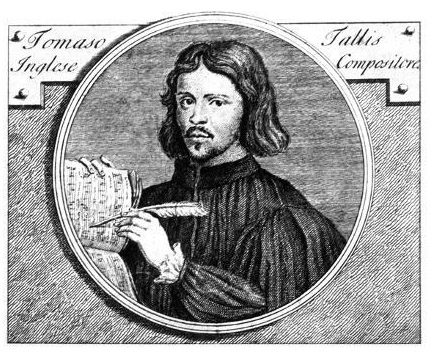

Tallis is ranked among England’s greatest composers and his name is synonymous with choral music. Oddly enough, we don’t even know what he looked like, because no contemporary portrait exists. The only picture we have was painted 150 years after the composer’s death by the engraver and art dealer Gerard Vandergucht, so there’s little reason to suppose that it’s a true likeness. In 1575, Queen Elizabeth granted Tallis and his younger contemporary William Byrd a patent to print and publish choral and vocal music, with exclusive rights to print any music in any language. Both Tallis and Byrd had the sole use of the paper used for printing music. At the time, it must have seemed like a gift from the gods.

Following prevailing fashions in Europe, it became customary for sixteenth century composers to set various texts from the biblical Book of Jeremiah. Tallis set the first lesson sometime between 1560 and 1569. This rich, powerful and beautifully-crafted music is typical of Tallis and the style of music that inspired so many other composers of the period. The music has a powerful, timeless quality – a sense of the serene and the eternal that reaches out to us over the chasm of time.

Thomas Tallis: Spem in alium. Gaechinger Cantorey cond. Hans-Christoph Rademann (Duration: 09:38; Video: 1080p HD)

All advanced music students have some knowledge of a composing skill known as counterpoint. It comes from the Latin punctus contra punctum which means “note against note”. It’s difficult to describe but boils down to the skill of combining several threads of melody to create a tapestry of sound, more expressive and interesting that the original melody. Today it’s often associated with the Baroque composer J S Bach whose music frequently used advanced contrapuntal techniques. However, elaborate counterpoint also flourished in the 16th century and many composers became remarkably skilled at using this technique, which was governed by precise rules and conventions. Today, music students often struggle with four-part counterpoint but the setting by Tallis of Spem in Alium (“hope in any other”) is a forty-part motet for eight choirs of five voices each. The prospect of composing a choral work with forty independent vocal parts would render most of today’s musicians apoplectic, or at least in search of a strong drink. Composed around 1570, this is a staggering technical feat and has been described as the composer’s crowning achievement. But the expressive quality of this magnificent music by Thomas Tallis is such that you’re not aware of the technical wizardly behind the notes. This is art that conceals art and the music speaks for itself.

|

|

|