You might recall the next bit of that poem by the Irish poet Thomas Moore: The harp that once through Tara’s halls, the soul of music shed, now hangs as mute on Tara’s walls, as if that soul were fled. The words reflect on Ireland’s struggle for independence and the suppression of its Gaelic culture during Moore’s time by portraying the harp as a symbol of silenced voices. The harp had been a political symbol of Ireland for centuries and has remained an Irish icon in one form or another since at least the sixth century. There’s a picture of an Irish harp on every label of that love-it-or-loathe-it dark Irish stout, Guinness.

I can appreciate the pleasure in playing this relatively small Irish harp that can be carried around with reasonable ease. But I sometimes wonder what possesses people to take up the modern orchestral harp, which is a different beast altogether. These massive instruments, also known as pedal harps or concert harps, typically stand about six feet high and can weigh up to about 40 kg (80 pounds). Unlike the piano, which is usually tuned by a professional tuner, harpists are expected to do it themselves. Tuning a harp is less of a hassle than tuning a piano, but it’s not as easy as tuning a guitar. There are 47 strings, all of which must be tuned separately so exceptional aural skills are required to do the job successfully. Many years ago, when I was a music student, I rarely heard a harp that was exactly in tune, though today, digital tuners make the task easier. Even so, this unwieldy instrument has always been the butt of musicians’ jokes, mostly concerning intonation.

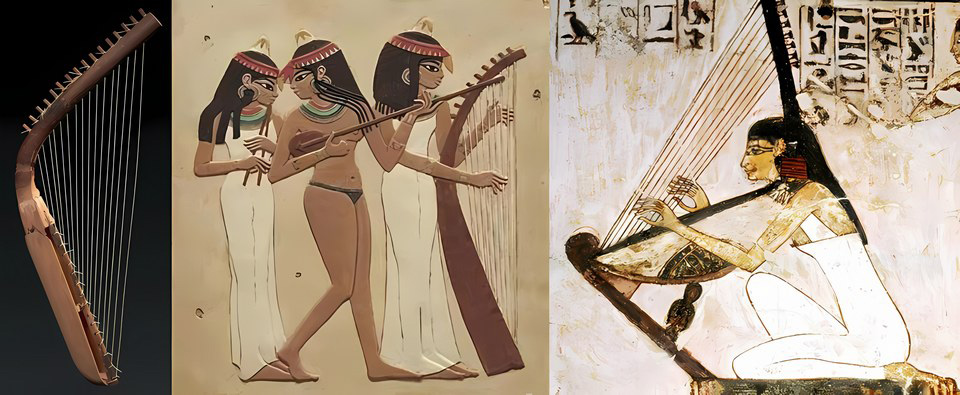

The harp has a long and distinguished history. Simple harps have been in existence ever since human beings discovered that strings tightened over a simple frame could produce a sound. The earliest evidence of the harp is found in ancient Egypt about 2500 BC, although it is possible the origins go back a further thousand years.

The harp has a long and distinguished history. Simple harps have been in existence ever since human beings discovered that strings tightened over a simple frame could produce a sound. The earliest evidence of the harp is found in ancient Egypt about 2500 BC, although it is possible the origins go back a further thousand years.

The Egyptian harp, or benet is one of the oldest instruments of Ancient Egypt. These simple harps were sometimes made from precious materials, and consisted of a long wooden neck with a small soundbox with strings attached. They usually had between five and ten strings. Harp-like instruments thrived for centuries in the Middle East. David, the harp-playing shepherd boy who famously slew Goliath and later became the second King of Israel (possibly during 10th century BCE) also played the harp. He probably played a small five or ten string harp, though how good he was is anyone’s guess.

The first harps that looked remotely like the modern instrument appeared in Europe during the 8th and 10th centuries. Most of them had only about ten strings. In medieval Europe, kings and chieftains had their own royal harpist who was held in high regard and could accompany poetry recitations and psalm singing. The instrument became immensely popular in Europe during the Renaissance and underwent many significant changes over the years.

The most important development was the invention of the pedal harp. Invented around 1720, when five (later seven) foot pedals were fitted to the soundbox at the bottom of the instrument. They are linked mechanically through the hollow column at the front of the harp to a complex mechanism which changes the pitch of the strings. Each pedal has three positions, corresponding to three different pitches. This was a breakthrough, because it allowed the harpist to play music in any key. It is especially important in the more harmonically complex music of the 19th century and beyond. The harp did not appear in the orchestra until the middle of the nineteenth century and it’s exotic sound proved irresistible to many composers. Many film music composers used it for its characteristic sound and its ability to create impressive, sweeping glissando effects.

As you might expect, orchestral harps with their complex pedal mechanism, don’t come cheap. Today, a student model costs about $15,000 US but a professional instrument could set you back well over $100,000. And you also need to buy a suitably large vehicle in which to cart it around.

For years, the harp was popular in Mexico, the Andes, Venezuela and Paraguay and although the instruments have slightly different designs, they have a common ancestor – the Baroque harps brought from Spain during the colonial period. Wales too has a harp tradition, ever since the instrument first appeared there in the late 17th century. The large Welsh harp is more like a modern concert harp in appearance and it remains an important part of Welsh culture.

Carl Dittersdorf (1739-1799): Harp Concerto in A major. Rosa Díaz Cotán (harp); Daniel Stratievsky (cond.) Neubrandenburg Philharmonic (Duration: 29:45; Video: 1080p HD)

Ass you can see, Dittersdorf was almost an exact contemporary of Mozart. In fact, he was a close friend of both Haydn and Mozart. They even played string quartets together with Dittersdorf on first violin, Haydn second violin, Mozart playing viola and the then-famous Czech composer Johann Baptist Wanhal playing cello. What an all-star line-up! Stylistically, the music of Dittersdorf is firmly rooted in the second half of the 18th century and became tremendously popular during his lifetime.

Carl Dittersdorf was born in a suburb of Vienna, and at the age of six, he began violin lessons. His father’s comfortable income allowed the young Carl not only a good general education at a Jesuit school, but also private tuition in music, violin, French and religion. As a young adult, he later played violin in various court orchestras and in 1771 he was accepted for the prestigious post of Court Composer for the Prince-Bishop of Breslau, who created a cultural centre based at Château Jánský vrch, now in the Czech Republic. Over the following twenty years, Dittersdorf wrote over 120 symphonies (even more than Haydn) along with many concerti and a German opera, which at the time brought him considerable fame.This harp concerto is the composer’s arrangement of his Concerto in A major for Harpsichord and Orchestra composed in 1779. It was quite common at the time for composers to make transcriptions of other previous works and of course, saved a great deal of time. As you’d expect, it comes in the usual three movements and it’s generally simple but attractive music, written in more in the style of light-hearted divertimento. The first movement is a jolly affair with some sparkling string writing and many solo passages for the harp. The slow movement is beautifully shaped with a charming fragile melody played on the solo harp revealing Dittersdorf as a composer of striking sensitivity. The playful last movement is attractive and compelling, a lovely example of eighteenth-century “easy listening” enhanced by clever woodwind writing and touches of humour.

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983): Harp Concerto. Emily Hoile (harp); Cornelius Meister (cond.) WDR Symphony Orchestra (Duration: 24:46; Video: 1080p HD)

The Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera (“Jee-nah-stay-ra”) is today considered one of the most important 20th-century classical composers of the South America. This concerto dates from 1956 and was first performed in 1965 by the Spanish harpist Nicanor Zabaleta with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy. Within twenty years, the concerto had become the composer’s most-performed work and it has since been performed worldwide and recorded many times. It is one of the most-performed harp concertos in the repertoire. It’s also one of the most technically demanding. The work is scored for standard orchestra minus low brass, with an extended percussion section that includes some native Latin American instruments. It also includes the rarely-seen keyboard instrument known as the celesta.

Based on folk dance rhythms of his native Argentina, the work opens with a typical spikey, rhythmic section which leads into a slower reflective passage dominated by the solo harp with wayward phrases from other instruments. Suddenly the insistent ostinato rhythm returns with exciting, sometimes thunderous interjections from the percussion. Ginastera reveals his enormous skill at light, transparent scoring, so that the delicate sounds of the harp are never lost in the orchestral texture. The final section of the movement is quite magical, as all the sounds begin to fade away and the movement end silently with the sound of a triangle and the ringing top notes of the harp.

A mysterious mood opens the second movement with an unworldly melody first heard on the low strings accompanied by a few bird-like chirruping phrases from the woodwind. The solo harp plays a strange, almost hymn-like passage and there’s a curious alien feeling about the music, as though being led into a dark, misty forest at night. The movement ends as mysteriously as it began and moves almost without a break into the final movement which opens with a dramatic and extended harp cadenza. This leads into a sudden change of mood with pounding percussion, scurrying strings and a compelling sense of excitement. Dominated by spikey dance-like rhythms this is Ginastera at his most characteristic; chugging repeated ostinato from the strings and woodwind, unexpected loud interjections from the many percussion instruments and a brilliant virtuosic harp part which uses extended techniques rarely found in conventional harp music. But Ginastera was anything but conventional, as this amazing work reveals.