“When shall we three meet again?” is, you may recall, the first line spoken in the Scottish play (for I dare not utter its name). It begins – somewhat unusually – with three people saying goodbye to each other, but the significance of the number three cannot have been lost on Shakespeare.

Apart from its religious significance, Pythagoras regarded the number three as “the noblest of all digits.” Western harmony is built on groups of three notes known as triads; in every key there are three major chords and three minor ones. Many works are cast in three movements and ensembles of three instruments are popular with composers. Haydn for example, wrote forty-five piano trios. I keep the set of CDs in the car, because with a total of ten hours playing time, there’s more than enough to help me endure the worst traffic jams that Bangkok has to offer.

A piano trio is not, as some people might logically assume, music for three pianos. Although it can be a work for piano and two other instruments, it’s nearly always for piano, violin and cello. Mozart wrote over twenty of them, Beethoven wrote thirteen and the obscure but prolific Carl Gottlieb Reissiger found time for twenty-three.

You might be wondering how this combination of instruments came about, so I shall tell you. But I’ll keep it short because I can sense your eyes glazing over already. Although its origins can be traced back to the Baroque, the emergence of the piano trio coincided, not entirely surprisingly, with the invention of the piano. Before then, people had to make do with the harpsichord, an instrument unflatteringly described by the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham as sounding like “skeletons copulating on a tin roof.”

At around the same time that the piano appeared, there was an increasing interest in home music-making and a type of composition known as the “accompanied sonata” became popular. In essence it was a piano sonata with optional play-along parts for other instruments. A flute or violin played more-or-less the same as the piano right-hand and the cello followed the bass line. This was partly for commercial reasons because a single work could be sold as a piano sonata, a violin sonata, or a trio.

Haydn’s early piano trios followed this same convention. But there was another issue, because eighteenth century pianos were not very powerful. A richer and more satisfying sound was produced by reinforcing the rather tinkly piano tone with the violin and cello. In Haydn’s later works, the string parts gradually took on more independent identities and some of his later piano trios – and those of every composer since – are for three instruments of equal importance.

This joyful, splendidly tuneful three-movement work dates from the 1790s and has a demanding piano part, particularly in the first and last movements. The video was made at the International Joseph Joachim Chamber Music Competition at which the Trio Gaspard won first prize. Hardly surprising too, because their performance is outstanding. Their exuberant playing is infectious, the phrasing is thoughtful, dynamics are carefully controlled and the articulation is spot-on. The last movement is given a thrilling performance, although I could have done with less theatre from the pianist.

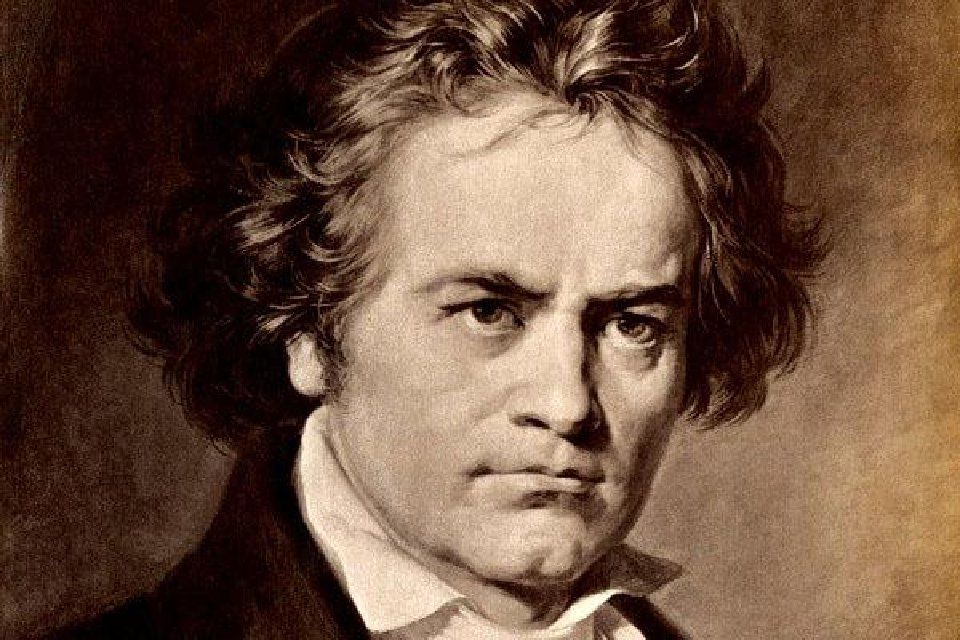

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): Piano Trio in E-flat major, Op. 70, No. 2. Trio Cleonice: Ari Isaacman-Beck (vln); Gwen Krosnick (vc); Emely Phelps (pno). (Duration 30:02; Video 1080p HD)

Beethoven continued the piano trio style where Haydn left off, but this 1808 composition inhabits a very different sound world and unlike most of Haydn’s trios, this has four movements. The string instruments are completely independent and at times even dominate – a complete reversal of Haydn’s approach.

By the early nineteenth century, pianos had a wider dynamic range, a larger range of notes and better resonance than models built fifty years earlier – absolutely right for Beethoven’s dramatic style of writing. This trio is full of memorable tunes and the superb last movement (22:06) turns into a real roller-coaster ride with sparkling playing from this talented young trio.

Oddly enough, the number three also reminded me of the story about Lord George Brown, who in the late 1960s was Britain’s famously boozy Foreign Secretary (and not to be confused with the other George Brown, who became Prime Minister). At a diplomatic reception Lord Brown allegedly requested a dance with another guest and received the imperious response, “I shall not dance with you for three reasons. First, because you are drunk. Second, because this is not a waltz but the Peruvian National Anthem. And third, because I am not a beautiful lady in red; I am the Cardinal Bishop of Lima.”