We have to thank William Wordsworth for the title. It’s a phrase from one of his sonnets and refers – surprisingly perhaps – to London. In July 1802, Wordsworth travelled from his home in the Lake District to the French seaside town of Calais. The journey necessitated passing through London and while there, Wordsworth sketched out his sonnet Composed upon Westminster Bridge which describes London and the River Thames in the early morning. In case you’d forgotten (or possibly never knew) it’s the poem that begins “Earth has not anything to show more fair…” referring to the misty view of London’s river. But of course, this was London in the early years of the nineteenth century. At the time, Wordsworth was thirty-two and already an established poet. He was almost exactly the same age as Beethoven.

He was one of many poets, painters and composers who found inspiration from London and if not from the town itself then from (to quote Wordsworth again) the “ships, towers, domes, theatres and temples” that brought character to the vibrant city. In 1901, Edward Elgar wrote his concert overture Cockaigne (In London Town) which was a lively musical portrait of Edwardian London. Gustav Holst of The Planets fame also wrote music inspired by familiar places in West London, notably Hammersmith and Brook Green. John Ireland composed A London Overture which at one point famously imitates the cry of a London bus conductor calling out the name “Piccadilly”. Eric Coates wrote two orchestral suites about London, one of which contained a march entitled Knightsbridge. This achieved national fame as the theme tune for the BBC Radio programme In Town Tonight which ran for nearly thirty years.

Please Support Pattaya Mail

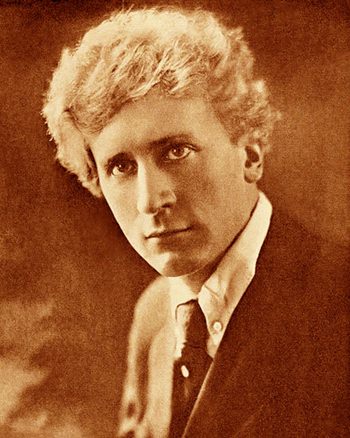

Percy Grainger (1882-1961): Handel in the Strand. Melbourne Symphony Orchestra cond. Sir Andrew Davis (Duration: 04:18; Video 720p HD)

Every Londoner knows the old music hall song Let’s all go Down the Strand. The locals usually shout the improvised line “Have a banana” into the chorus, though no one seems to know quite why. The Strand is one of London’s most interesting streets though it’s less than a mile long. It was popular for centuries and many important mansions were built between the Strand and the nearby River Thames. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries The Strand became well-known for its coffee shops, taverns and restaurants and it was certainly a thriving street when Handel lived in London during the first half of the eighteenth century. He must have wandered along The Strand many times, possibly even with a banana.

The eccentric Australian pianist and composer Percy Grainger initially called this piece, perhaps somewhat unimaginatively, Clog Dance but later he changed the name to Handel in the Strand which seems to have a better ring to it. It is typical Grainger; light-hearted and slightly folksy with some catchy melodies. In his day he was considered an outstanding pianist but as a composer he didn’t produce any symphonies or concertos. This led some critics to assume that he probably couldn’t. Most of his compositions were less than seven or eight minutes in length. However, modesty was not Grainger’s strong point and he pronounced his own music superior to that of both Mozart and Tchaikovsky. He’s usually associated with the English folksong Country Gardens which he arranged in 1918 for piano and orchestra.

Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): Symphony No. 2: A London Symphony. Spanish Radio and Television Orchestra cond. Carlos Kalmar (Duration: 48:59; Video 480p)

Vaughan Williams began writing this symphony in 1908; the score was completed in 1914 and the work was first performed in London the same year. The composer then sent the manuscript to the conductor Fritz Busch in Germany for his consideration but the score was accidentally destroyed, giving the symphony the dubious honour of being one the first casualties of the First World War. In 1920 the score was reconstructed from the instrumental parts but the composer took the opportunity to revise it. It was later revised yet again with about twenty minutes’ worth of music hacked out of the original.

Although Vaughan Williams originally claimed that the music was not programmatic, he seems to have later changed his mind. The atmospheric day-break music at the start echoes the sentiments of Wordsworth’s sonnet and we even hear (at 03:03) the Westminster chimes on the harp. Vaughan Williams said that the second slow movement is intended to evoke Bloomsbury Square on a November afternoon and to appreciate the third movement he suggested that “the listener should imagine himself standing on Westminster Embankment at night, surrounded by the distant sounds of The Strand, with its great hotels… crowded streets and flaring lights.” The rich and powerful last movement depicts the Thames passing, and along with it London’s Edwardian days of glory. As the excitement dies down the Westminster chimes are heard again (at 43:45) and the mood returns to that of the beginning, drawing this great symphony to a reflective and melancholy conclusion.

|

|

|