I don’t know about you, but I seem to have an aversion to snakes. Now I’m sorry if you are a snake-lover but I can’t stand the wretched things, largely because they give me the creeps. Of course, this is totally irrational and probably unfair to snakes, but that’s how it is. And what are they for anyway? They just seem to laze around all day. Mind you, that’s probably not much different to some of the foreign residents in these parts.

Wasps don’t do much for me either because they can be unpleasant little beasts when they put their minds to it. Strangely enough, an ominous-looking wasps’ nest has appeared on a lighting pole in my soi causing considerable consternation to the night-guard. At least, their presence might encourage him to stay awake.

The other day I discovered why some wasps are relatively benign while others seem irritable and unreasonably aggressive. Apparently, it’s all to do with the queen wasp who decides what the “mood” of the nest is going to be and then emits a chemical called a pheromone. This has some kind of mind-altering properties which affect the behaviour of the lesser wasps. Of course, all this is irrelevant to a classical music column but I just thought you’d like to know. Anyway, back to the snakes.

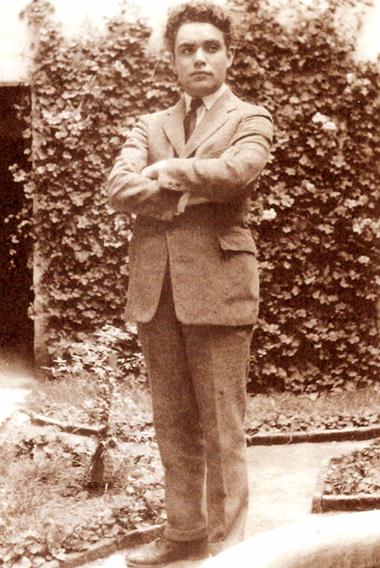

Silvestre Revueltas Sánchez was one of Mexico’s leading musicians in the first half of the twentieth century. He first achieved fame as a concert violinist and was later appointed Assistant Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Mexico. He wrote songs and chamber music but he’s best-known for his dramatic film music, particularly his score for the 1939 Mexican movie La Noche de los Mayas.

He used clashing dissonances with abandon and many of his works have a passionate rhythmic vitality and raw visceral energy. Sensemayá dates from 1938 and was inspired by a poem by the Cuban writer Nicolás Guillén which evoked a ritual Afro-Caribbean chant performed while killing a snake. Originally the music was scored for small orchestra but the composer later changed it into a full-scale orchestral work calling for nearly thirty wind instruments, fourteen percussion and strings.

Guillén’s poem refers to a mayombero, a man skilled in herbal medicines and arcane rituals. One of the main rhythmic motives in Sensemayá is derived from the repeated chant of the mayombero and evidently used in an actual snake-killing ceremony. The music begins quietly and ominously and the volume gradually builds up over an obsessive, ritualistic pounding rhythm. There are moments which might remind you of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring but this is an unmistakable Mexican voice that evokes the exotic legends and beliefs of another age. The rhythms are powerful and hypnotic: just listen to the complex surging patterns of sounds that Revueltas creates at around 06:32 onwards.

These young Americans give a terrific performance. The orchestra was established in Portland, Oregon in 1924 and is the longest-established youth orchestra in the country. It would have been immensely satisfying to tell you that its emblem is a writhing snake. But unfortunately, it isn’t.

If there’s a choice between having a snake and a wasp, I’ll have a wasp, thank you very much. Contrary to popular belief, this overture is not really about wasps at all. It’s about people who behave like them. Or so thought Aristophanes, who in 422 BC wrote a play called The Wasps. It was a caustic satire that ridiculed the Athenian law courts, the juror system and the bickering old codgers who chose to become jurors. They’re described in the play as being “as terrible as a swarm of wasps, carrying below their loins the sharpest of stings”.

Corpus Medicorum is made up of doctors, medical students and other health professionals who also happen to be musicians. It was founded in 2002 and gives concerts to raise funds for Lung Cancer Services at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

In 1909 Ralph Vaughan Williams was invited to write the incidental music for a production of the play at Cambridge. He later adapted the music to create a suite of five movements, the overture being the first. It’s become a favourite concert piece in its own right although the other movements are sometimes also performed, one of which is intriguingly entitled March-Past of the Kitchen Utensils.

Apart from the opening fifty seconds of wasp-like buzzing sounds, the music doesn’t have much to do with wasps or even ancient Greece. It’s pure Edwardian England, full of wholesome folk-like tunes and about as far from Athens as you can get. Musically it’s a lot closer to Nether Wallop-in-the-Gruttocks.

|

|

|