On Thursday, 11th September 1591 John Baldwin added the finishing touches to his elegantly hand-written collection of keyboard music, entitled My Ladye Nevells Booke.

Baldwin was one of the most famous music calligraphers of the day and this heavy, oblong volume of nearly two hundred pages must have been a gargantuan undertaking. It’s one of the finest Tudor music manuscripts in existence and contains forty-two pieces by William Byrd, the greatest English composer of the age. But strangely enough, the identity of Lady Neville (to use the modern spelling) remains a mystery. She could have been one of several people, but she was clearly of noble birth because the coat of arms of the Buckinghamshire Neville family appears on the title page. And that’s about as much as we know for sure.

The book contains music written by Byrd during the previous fifteen years and most of the works are short pieces of dance music including some sombre galliards and pavans. But more importantly, the book also contains some of the first descriptive pieces ever written, a suite called The Battell. There are nine short movements with names like The Souldiers Sommons, The Marche of Footemen, The Marche to the Fighte and so on.

To modern ears it sounds charmingly naïve, especially as the pieces would have been played on a tinkly-sounding clavichord. Nevertheless, the notion of music actually describing something must have seemed a novel idea at the time. Even four hundred years later, it’s safe to say that most music doesn’t describe anything at all.

In the byways of musical history there are other pieces of music which attempt to describe warfare of some kind. The 1620s saw the first performance of Monteverdi’s Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, a work for voices and instruments that contains a theatrical battle scene. Then there’s Beethoven’s crowd-pleaser, written for huge orchestra called Wellington’s Victory and Tchaikovsky’s old pot-boiler, the 1812 Overture. Liszt wrote a heroic symphonic poem called The Battle of the Huns and Prokofiev wrote several works influenced by war themes. Oh, and let’s not forget Britten’s impressive War Requiem. But perhaps the most disturbing music that depicts the horrors of war is by an English composer with a foreign-sounding name.

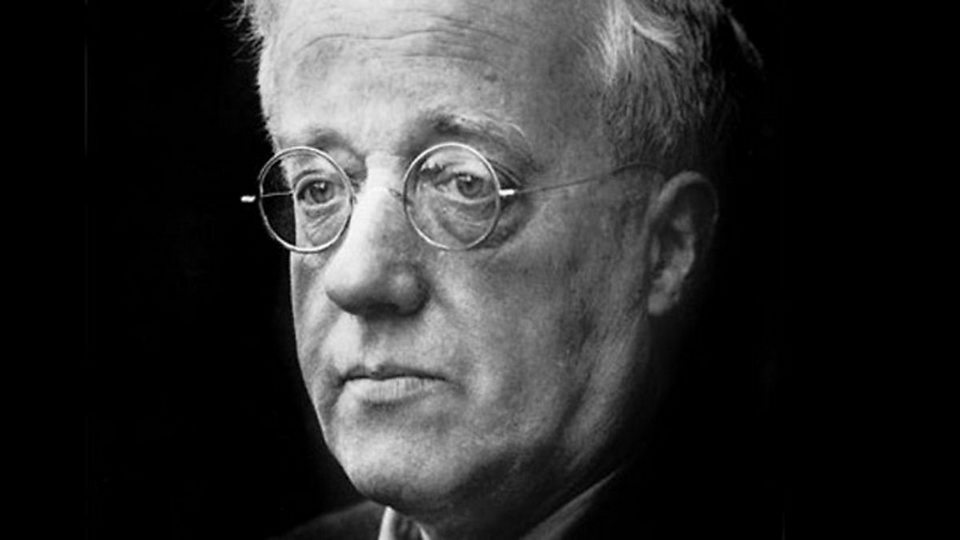

The Planets is Holst’s largest orchestral work and it’s also his most popular. But if Holst hadn’t gone on holiday to Mallorca with a group of friends in the spring of 1913, it may never have been written.

In Mallorca, Holst was introduced to astrology by Clifford Bax, the brother of composer Arnold Bax. It was evidently Clifford who gave Holst the idea for the composition. He started the work in 1914 and completed it two years later. After its first performance in 1920, it became a huge success and has remained so until the present day, with its brilliant orchestration and rich melodic invention.

The first movement Mars – The Bringer of War has been described as the most devastating piece of music ever composed. Unusually, the piece has five beats to the bar and an ominous insistent rhythmic pattern dominates the entire movement.

At the opening, the strings play this rhythm col legno which involves hitting the string with the wood of the bow, producing an eerie percussive sound. The movement builds up tension throughout, with a menacing quieter middle section. This is not a battle with bows and arrows; it’s about the horrors of mechanized warfare emphasized by the composer’s use of pounding percussion, grinding, clashing harmonies and of course the incessant relentless rhythm. Gradually the music lumbers towards its inevitable climax, leaving us with a sense of poignant loss and desolation.

This is the last movement of Respighi’s 1924 suite in which the four movements depict pine trees in various parts of Rome at different times of the day. Ottorino Respighi is best known for his orchestral music and especially the three symphonic poems: The Fountains of Rome, The Pines of Rome and Roman Festivals.

This final movement, superbly conducted by Georges Prêtre, begins very quietly and portrays the Appian Way in the misty dawn, while in the far distance a massive legion marches under the brilliance of the rising sun. The soldiers get closer and closer as the intensity of the music increases. Respighi wanted the “ground to tremble under the footsteps” of the advancing army and uses an organ playing its lowest notes. The piece is a gradual crescendo which rises to a thunderous climax with joyous brass fanfares, as the army triumphantly marches towards the Capitoline Hill.

|

|

|