Last night I was re-reading Jeremy Paxman’s entertaining and brilliantly perceptive book The English: a Portrait of a People. At least, I was attempting to re-read it but was distracted by the sound of an open-air disco going on somewhere across the fields. It was quite a long way off but the thudding incessant bass and the repetitive, mind-dulling noise of techno-rock made concentration almost impossible. You will probably say, “This is Thailand; what’s new?” But while the distant music was pounding relentlessly, it occurred to me that over the centuries, music has gradually become louder, even without the aid of electric amplification. The eighteenth century orchestra for example, was quieter than those of today partly because it was smaller but also because instruments produced softer sounds.

For a moment, let’s cast our minds back to the early Middle Ages, the so-called “dark ages” that lasted between the fifth and the tenth centuries. The beginnings of western classical music lie somewhere here in the plainchant of the Roman Catholic Church. These chants were unaccompanied melodies sung by small groups of nuns, monks or other clerics rather than by trained singers. But just imagine how quiet it must have been when the loudest musical sound was that of a few human voices.

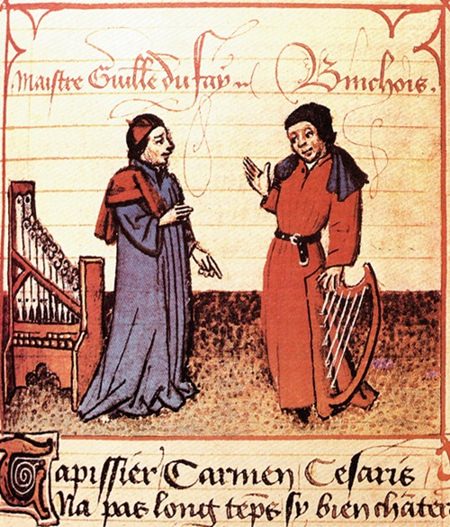

Guillaume Dufay (left) with composer Gilles Binchois.

Guillaume Dufay (left) with composer Gilles Binchois.

During the early years of the Middle Ages, the chants were passed on by memory alone but in the early ninth century the Emperor Charlemagne decreed that the music be written down and plainchant books be distributed to churches and monasteries across Europe. Whether we like it or not, we have to thank the early Christian church for the preservation and development of the earliest classical music.

Sometime during the early Middle Ages, a musical style known as organum appeared. It had nothing to do with organs but referred to the practice of improvising a second vocal part in parallel with the melody. It was usually sung a perfect fourth or fifth below and produced that stereotypical “medieval sound” that is so easy to recognise today. A supporting part was often added in the form of a single sustained lower note like the drone of a bagpipe.

Pérotin (1160-1225): Sederunt Principes. The Hilliard Ensemble (Duration: 10:50; Video: 1080p HD)

The two composers Léonin and Pérotin worked at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Léonin was about ten years older and had developed the previously improvised organum into an art-form.

Pérotin perfected the technical feat of writing organum in three and four parts. He used Léonin’s technique of taking a simple Gregorian melody and literally stretching it out in time. In Sederunt Principes, the first syllable “se” is drawn out for well over a minute and sung to a long melodic line. At the same time, he created second and third voices that interweaved with the melody producing a fascinating rhythmic counterpoint of vocal sounds.

The foundation of the music was the conventional low-pitched drone but sometimes Pérotin changed the notes to create a sense of contrast. The Bishop of Chartres wrote that Pérotin’s music “drives away care from the soul and… confers joy and peace and exultation in God, and transports the soul to the society of angels”.

This recording is audio only but the music appears on screen in modern notation. If you can read music you’ll get a fascinating glimpse into Pérotin’s composing style. But if you don’t, just sit back and enjoy the music. Using the text from Psalm 118, Sederunt Principes is a hymn for the mass of the Feast of St. Stephen and notice the incredibly beautiful harmonies at about 03:50 for the plea Adjuva me (“Help me”). It’s haunting, powerful music that speaks to us passionately and eloquently across the centuries.

Guillaume Dufay (1397-1474): Nuper rosarum flores. Quire Cleveland, dir. Ross W. Duffin (Duration: 06:08; Video: 1080p HD)

If we jump forward in time a couple of hundred years, we’ll find that although music hasn’t got much louder it has certainly become more complex and expressive. During the mid-fifteenth century Guillaume Dufay (sometimes written du Fay) was regarded as the leading composer in Europe. Just listen how music has moved on from the time of Pérotin.

Although it’s probably not obvious, this work is also based on Gregorian chant and even though its medieval origins are unmistakable, the overall sound is mellifluous, rich in harmony and it has more sophisticated melodies.

This work was written in 1436 for the consecration of Florence cathedral and the piece is constructed using duration ratios of 6:4:2:3 for each section. Now this might seem an irrelevant snippet of information but the American musicologist Craig Wright discovered that this ratio is exactly the same as the dimensions of the biblical Temple of Solomon and is also roughly the same ratio of dimensions of Florence cathedral itself. Now if that’s not a fascinating revelation, I don’t know what is.