Do you remember that song called My Grandfather’s Clock? I bet you didn’t know that it was written back in 1876. You may recall that the song was about a clock which worked for ninety years but stopped for good when its grandfather owner breathed his last. The song was most famously recorded by Johnny Cash and remained a standard for years in Britain and America. The composer, one Henry Clay Work was self-taught and also wrote the rather more jubilant Marching through Georgia.

PM In-article Google in text

I suppose one of the other best-known popular pieces of music about clocks is Leroy Anderson’s number called The Syncopated Clock which he wrote in 1945 while serving with the U.S. Army. Although a gifted linguist (he was fluent in nine languages) he made his name in light music, notably with simple but effective pieces like Blue Tango, The Typewriter and Sleigh Ride. Even so, his catchy tunes have the habit of becoming irritatingly lodged in the memory in the same way that bits of chicken get stuck between the back teeth.

Prokofiev imitated the sound of a clock to strike midnight in his ballet Cinderella and Kodály creates an image of an elaborate musical clock in his opera Háry Janos. At one point in the Richard Strauss opera Der Rosenkavalier, there are thirteen strikes of the clock in the orchestra, created by using a celesta and two harps. The beginning of the second movement in Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony sounds as though it’s imitating something mechanical. There’s a widespread belief that the effect is supposed to be an imitation of a metronome, one of which had recently been produced by Beethoven’s friend Johann Maelzel. But no one really knows for sure.

In 1998, the British composer Harrison Birtwistle wrote a set of five piano pieces called Harrison’s Clocks, challenging for both performer and audience alike. The work was inspired by Dava Sobel’s short book Longitude which tells the fascinating story of the eighteenth-century English clockmaker John Harrison and his mission to build an accurate chronometer for use at sea.

Einar Englund’s ravishing Fourth Symphony has a sizzling second movement which includes many clock-like sounds of chiming bells, frenetic ticking and imitations of ponderous clockwork mechanisms. It’s a shame that the music of this extraordinary Finnish composer is so rarely performed.

This jolly one-act opera is dominated by clocks and set in 18th century Spain. It’s a comedy involving a desperately over-sexed Spanish woman arranging secret assignations with her various lovers, while her husband innocently occupies himself with clockwork mechanisms and services the municipal clocks in the town of Toledo.

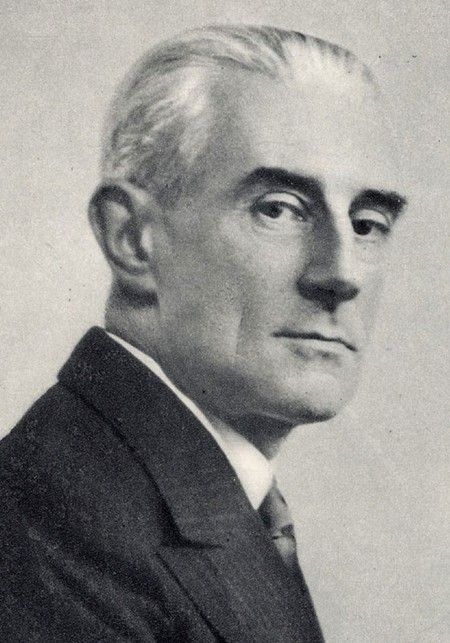

L’heure Espagnole (“Spanish Time”) was first performed at the Paris Opéra-Comique May 1911 and Maurice Ravel created a Spanish flavour by using ideas from traditional Spanish dances. It was produced in Britain for the first time at Covent Garden in 1919 and in the following year it was seen in Chicago and New York.

The piece sometimes descends into pure farce in which various characters are obliged to hide in clocks and it has become one of the most popular operas of the twentieth century. This Glyndebourne production dates from 1987 and it’s sung in the original French. However, there are also English subtitles which might be useful if your French is a bit rusty.

The Austrian composer Joseph Haydn wrote at least 104 symphonies and the so-called “London” symphonies are perhaps his best-known. They date from between 1791 and 1795 and as you may have guessed, were intended for performance in London. They’re in the usual four movements and apart from No 95 they all have a slow introduction to the first movement, one of Haydn’s personal trade-marks.

Symphony No 101 was premiered in March 1794 and its nickname “The Clock” comes from the second movement (at 07:55) in which a distinct ticking sound dominates the movement. Haydn’s music was hugely popular in London at the time and the audience was wildly enthusiastic. The reporter for the London newspaper “The Morning Chronicle” waxed lyrical: “As usual the most delicious part of the entertainment was a new symphony by Haydn; the inexhaustible, the wonderful, the sublime Haydn! The first two movements were encored and the character that pervaded the whole composition was heartfelt joy.”

The symphony proved so successful that a second performance was arranged a week later. It is indeed a wonderful composition which has stood the test of time and well over two hundred years later it remains one of Haydn’s most popular works. This Japanese orchestra gives a fine performance and the symphony is worth hearing all the way through, if that is, you’re not watching the clock.

PM In-article Google in text

|

|

|